A Kodak Brownie No.2 Model F released in 1924. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

The start of the 20th century marked the advent of popular personal photography. Previously, commercial photography studios were the only ones producing prints, as the barrier to entry was high; the materials needed were large, expensive, and required experience. The glass plate negatives and large format cameras were better suited to studio use than photography on the fly. But this inaccessible nature was about to change due to the business savvy of George Eastman and his Eastman Kodak Company. With years of expertise in crafting cameras and film, the company released the legendary Kodak Brownie camera in 1900.

This simple machine distilled the camera to its basic elements, making it cheap and easy to use. With a powerful marketing push to amateurs—especially youth—Kodak sold over 150,000 Brownie cameras in the first year of production. Over the next 70 years, Kodak built upon this success with countless new models and updates.

Millions of Brownie cameras of varying varieties were purchased and made photography an affordable part of everyday life. As much as Kodak became synonymous with the heyday of film photography, the Brownie camera became iconic for its snapshots. The ability to capture the small moments of life at a whim proved an important facet of the 20th century.

Read on to learn more about the Kodak Brownie—the camera which got the world hooked on photography.

The Earliest Kodak Brownie Cameras

“Waiting for the President,” June 19, 1922. A girl referred to as “Little Miss Tarkington” waits with a Kodak Brownie box camera to take a picture of Warren G. Harding. (Photo: National Photo Company Collection/Library of Congress)

Designed by Frank A. Brownell, the unique name is inspired by the mischievous spirits called brownies which populated European folklore. The little sprites presented just the right casual and youthful vibe for what Kodak hoped would be a popular and accessible camera. The original Brownie sold for one dollar ($31 in 2021). The required 117 mm film was likewise affordable, as was processing your shots by sending them to Kodak or at a local lab.

The original Brownie was produced in 1888 and released in February of 1900. It's an example of a box camera. The basic premise is simple; a lens (a hole, usually uncovered in the early years) fronts the camera. Many box cameras offered a tab that could be pulled to offer a smaller aperture for brighter light scenarios. Behind the lens is a simple shutter mechanism. Typically only one shutter speed was available—plus a bulb option to leave the shutter open.

Each exposure was made by pressing a lever on the side of the camera. At the internal end of the box, the camera obscura effect exposed the loaded film. The winding knobs on the side of the box allowed the frames to be advanced between shots, and a little red window on the back let the user count their frames. Modern photographers will be accustomed to the viewfinders of a DSLR, but in the days of box cameras, little mirrored viewfinders on top of the camera were the best way to align your image.

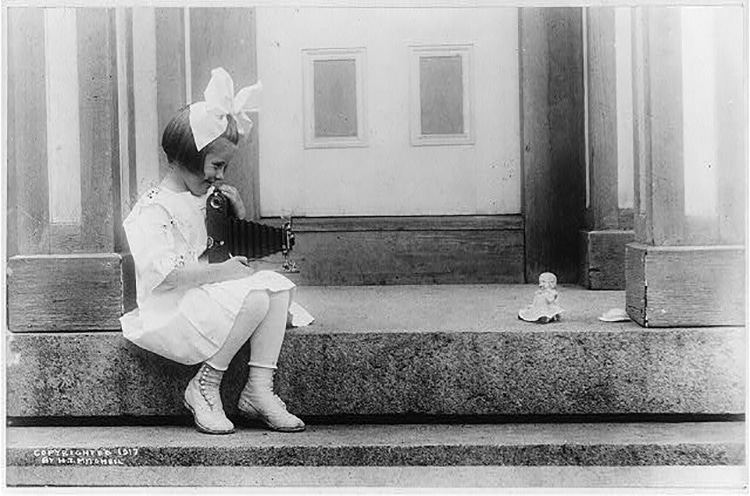

A young girl in 1917 with a folding Brownie camera, perhaps the No. 2 Autographic Brownie which was first released in 1915. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The negatives produced were originally square—2.25 inches on each side. Over time, new box shapes used different size films and produced varying sized negatives.

Kodak produced many versions of their box Brownie camera including the popular No. 2, which introduced 120 film. However, due to the incredible success of their new consumer cameras, Kodak began to use that particular film for other types of affordable equipment. It debuted a line of folding cameras that used 120 film. These cameras had bellows stretching the distance between the lens and the emulsion on the film, thereby producing a large image. However, unlike the box Brownie, the folding Brownie models could be easily folded to be slipped inside a pocket or briefcase. The folding pocket Brownies and autographic Brownies were produced for years and were very popular.

Plastic and the Mid-Century Brownie

RabbitFlatsAntiques | $27

Box Brownies continued to be produced through the 1950s, however other materials were used in new versions of the camera. Most important was the synthetic plastic Bakelite. Patented in 1909, an early Kodak Bakelite camera was the “Baby Brownie.” This small device was released in 1934 and used 127 film. Like the box Brownie, the mechanism of the shutter, lens, and film advance was very simple.

Kodak got creative with their iconic plastic cameras of the Mid-Century period. There are many varieties you can still find for cheap on Etsy, eBay, or at garage sales. One fun example is the Brownie Reflex Synchro which was released in 1941. This camera was in response to the popularity of twin-lens reflex cameras (TLRs). In a true TLR like a Rolleiflex, the shooting lens and the focusing lens are coupled so that the user can focus their image using a ground-glass screen. But on the Reflex Synchro, there are no focusing options; the image can be roughly framed using the glass screen under the camera's hood.

EastCoastOptics | $75.99

An iconic mid-century model is the Brownie Hawkeye Flash which could be coupled with an electric flash. The Bakelite body and mechanisms functioned much like the Baby Brownie and the box Brownies. But with only one aperture, one shutter speed, and bulb mode, the Brownie Hawkeye could not focus closer than about five feet. The Hawkeye used 620 film, a format developed by Kodak in 1931. It is commonly thought this switch from 120 to 620 was a marketing ploy. The emulsive surface of the film is the same, however, the paper backing and spool are differently sized. In short, it benefitted Kodak if all their cameras would only accept Kodak film.

KitschyVintage | $22

Many plastic Brownie models were also created for 127 film—slightly smaller than the 120 format. Among these models were the Brownie 127, the Holiday Brownie, and the Brownie Bullet. Once more, the simple mechanisms of the cameras offered ease of use but little sophisticated control. 127 film is no longer commercially produced today, but you can find sellers on Etsy who cut down the 120 format. (Some photo suppliers also carry film adapted to 127 cameras.) While it may seem like there is nothing special to the simple mechanics of the Kodak Brownie, their simplicity, portability, and surprising versatility kept a “Brownie” model camera in production until 1986.

The Kodak Brownie Today

Film Photography Project | $13.99

Because of the sheer number produced over the decades, most antique Kodak Brownie cameras are very affordable today. You can find them on Etsy, eBay, or antique stores. You may even want to go through your relative's attic, as almost everyone had a Brownie camera. Because the cameras are mechanical, they often still work as new. If you buy a Brownie to experiment with a vintage camera, check that the shutter still fires, the inside is clean, and the film advance works. If so, you are off to a great start.

Making 127 film on your own is rather complex, but making 120 film work in 620 cameras is simple. You can also re-roll it onto old 620 spools in a film-changing bag.

The magic of the snapshots produced by a Brownie camera holds true today. To learn more about this legendary run of cameras—or to identify one you are not sure about—check out this comprehensive list by the The Brownie Camera Guy. If you approach the Brownie expecting vintage magic, you won't be disappointed.

Related Articles:

How the Development of the Camera Changed Our World

The History of Camera Obscura and How It Was Used as a Tool to Create Art in Perfect Perspective

Get an “Instant” History of How Polaroid Revolutionized Photography

Young Student Secretly Photographs People with Hidden Spy Cam in the 1890s