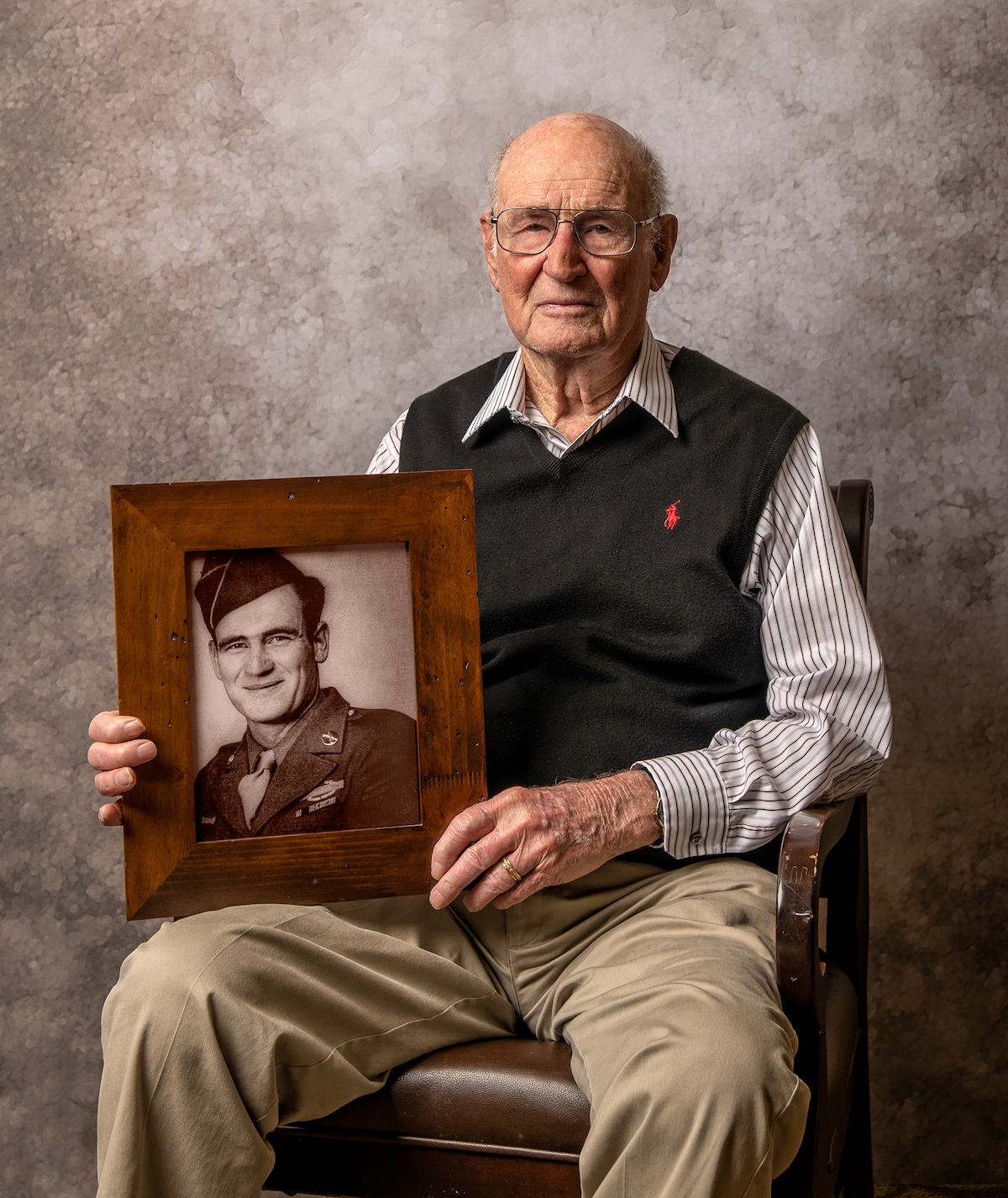

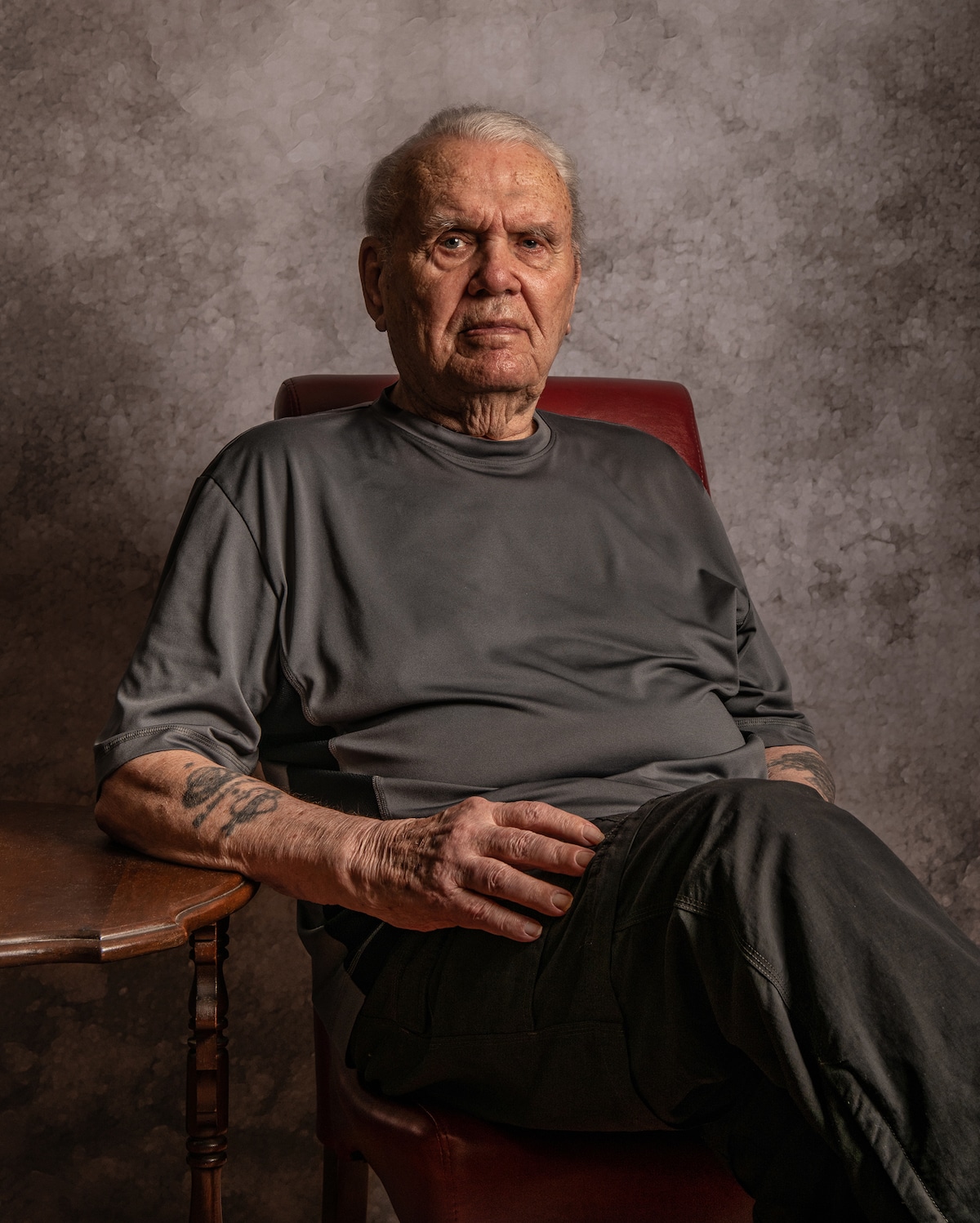

Army Corporal Gabe Kinney

Portrait photographer Jeffrey Rease has set out to immortalize The Greatest Generation—specifically those who served during World War II. Over the course of six months, he has already amassed over 60 portraits of World War II veterans for his Portraits of Honor series and sees no end in sight. By meeting these brave men and women, listening to their stories, and taking their portrait, Rease is creating invaluable memories of a generation that will soon be lost.

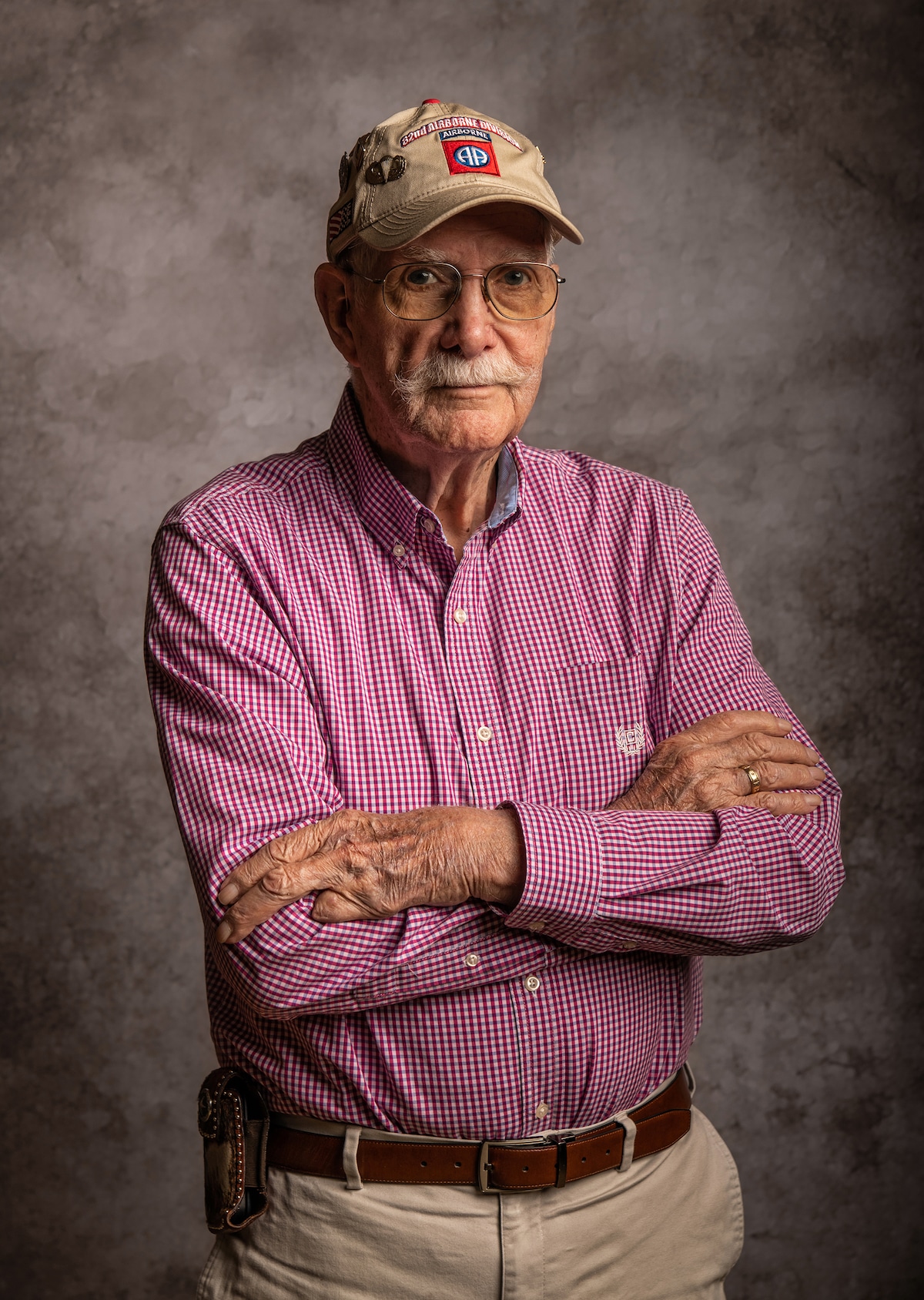

Set against a minimal backdrop, these veterans sit with pride and honor—many donning their uniforms and occasionally holding portraits of themselves in service. It's a personal project that has special meaning for Rease, who has many family members who have served. By connecting with these veterans, he hopes to give back and to educate a younger generation who may not realize the sacrifice and heroism of these men and women.

Rease started with veterans local to his area and, as word has spread, he has begun to branch out in different directions. He documents his experiences on his blog, bringing the public into his journey as he comes face to face with veterans from all branches of the military. As he dialogues with them, he's able to understand more about their personal journeys and is able to bring these life experiences into the final portrait. By sharing their portraits and personal stories with the public, Rease is bringing the bravery of the past into the present.

We had a chance to speak to Rease about the motivation behind the project, how he came upon his first veteran, what he hopes people take away from the work, and how WWII veterans can participate. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

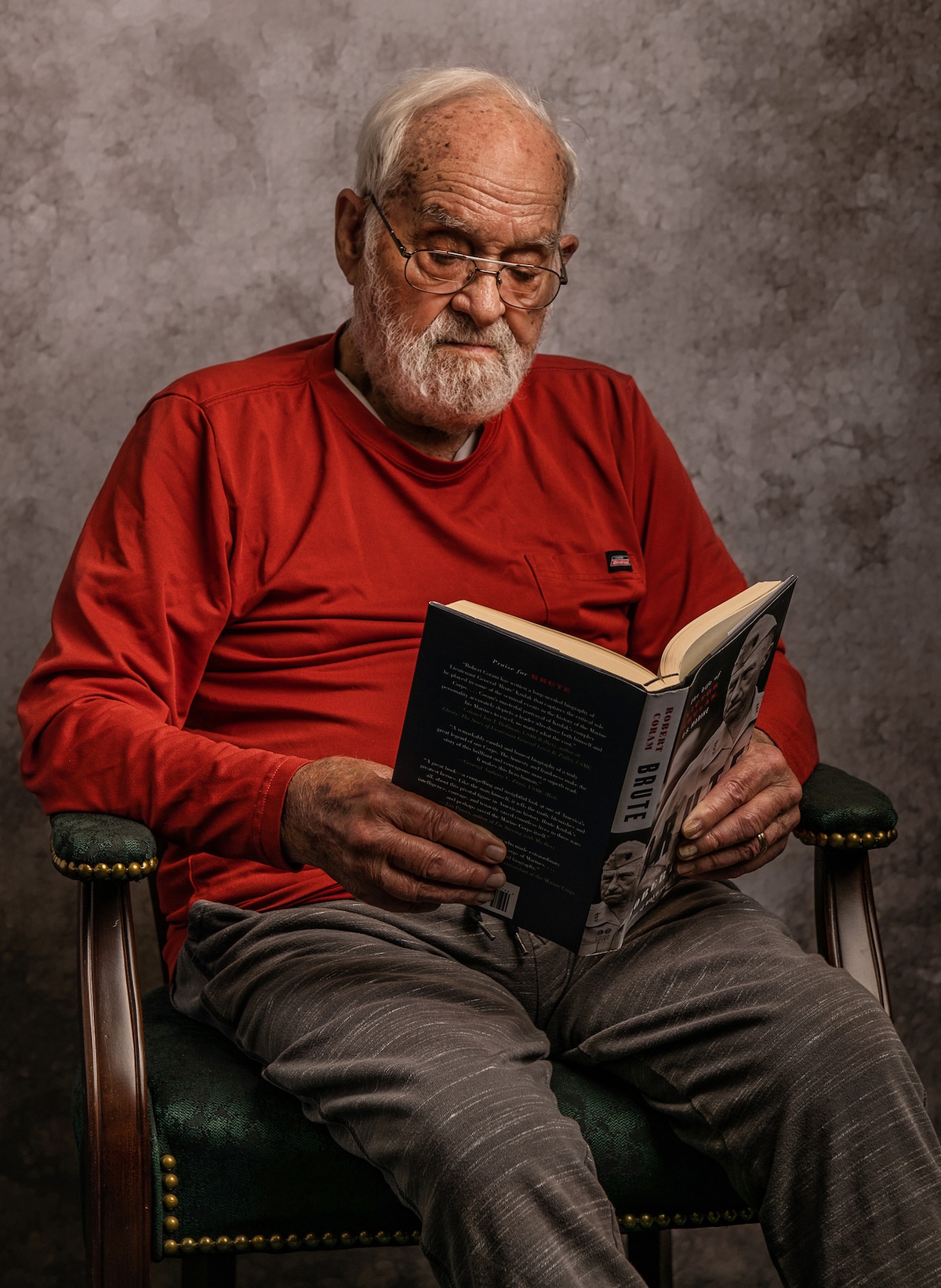

Marine Lieutenant Colonel Carl Cooper

What inspired Portraits of Honor and how long have you been working on it?

As a photographer, I love to shoot portraits of people and I’ve always had some interest in WWII and military history. I grew up reading stories of WWII heroes and watching movies about the war. It was a good fit to combine the two interests. Also, a photographer I know in the UK named Glyn Dewis has a wonderful project photographing British WWII veterans. His photographic style and project development have been a big inspiration to me.

I started my project in April 2019. A local football team was honoring veterans at its home games and I saw a news report of one being honored. It was Colonel Carl Cooper, a 99-year-old Marine Corps veteran standing on the field wearing his dress blues uniform that he retired in after 38 years in the Marines. I instantly knew he would be perfect to include in my project! I found out that he lives in my area, and after some contacts were made, I was able to schedule a photoshoot with him at his home.

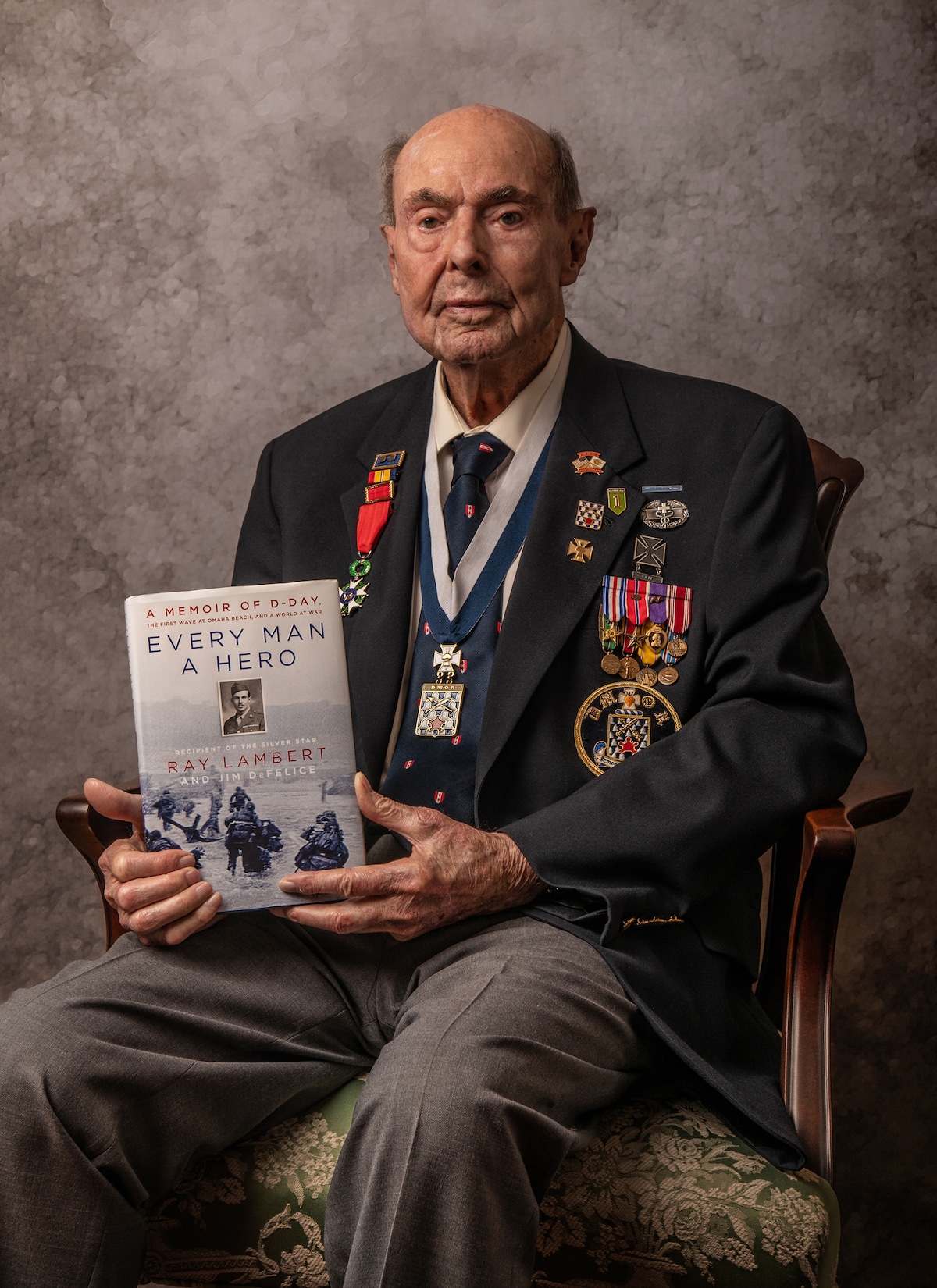

He was eager to do the photoshoot and he is as nice a person as anyone could meet. It was after that experience of meeting and speaking with him that my project became a passion of mine, and now I cannot imagine not doing this. I will continue doing it as long as I can. Like one of the D-Day veterans I photographed, Army Medic Sgt. Ray Lambert, told me, “Lord, just let me get one more!”

Army PFC Brad Freeman

You have an uncle who fought in WWII. When did you first learn his story and how did this impact you?

There are several members of my family who served in various military branches. My father was an Army Airborne paratrooper in the Korean War. Other uncles also served in Korea. My brother and my own son served more recently in the Marine Corps.

But my mother’s brother, Huey Bracknell, died in WWII serving in the U.S. Coast Guard. On March 10, 1944, the German submarine U-255 torpedoed the destroyer escort on which he served, the USS Leopold, in the north Atlantic. Only 28 survivors were rescued while 171 others died in the explosion on board or in the cold water.

I learned details of it only later in life as my parents met survivors or read their stories. So, perhaps wanting to hear stories like that from people who were there influenced me and helped me to find and meet more WWII veterans and learn more about their stories—many of which haven’t been told before. I think their families really appreciate it.

Navy Hellcat Fighter Pilot Dick Pace

How did you go about meeting the veterans you photographed in the beginning?

After meeting and photographing Colonel Cooper, I posted his story on my Facebook page. His nephew shared it and a friend of his mentioned that his father-in-law is a WWII veteran, a surviving member of “Merrill’s Marauders,” an Army unit that fought through rugged mountains and dense jungle in Burma. From there, I had people tell me of WWII veterans in retirement communities, Veterans Administration homes, volunteers at the National Naval Aviation Museum, and in communities around my state of Alabama. Social media and word-of-mouth have been a great resource for me to find more veterans.

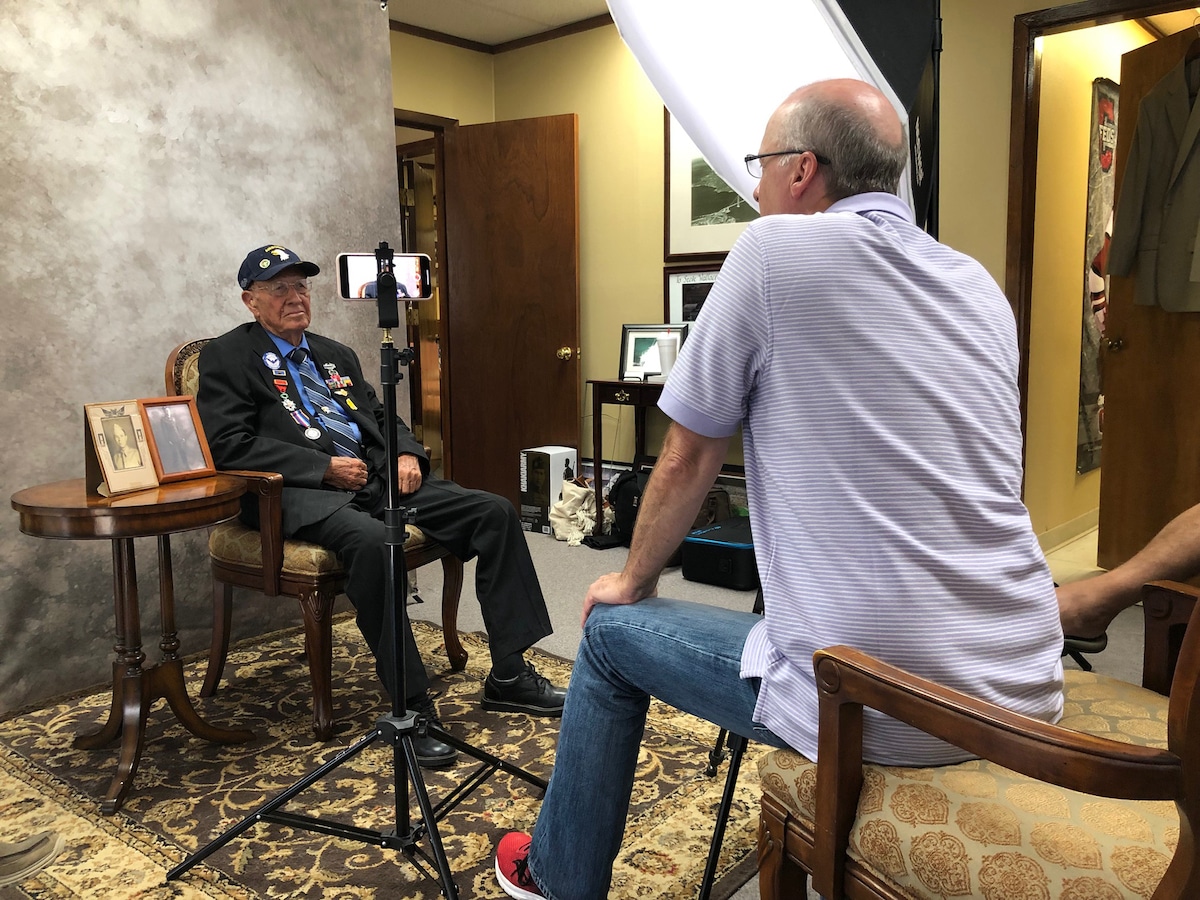

Behind the scenes of photoshoot with veteran Brad Freeman.

What was the process of getting them to open up like?

Not every veteran has wanted to be photographed and interviewed. Many cannot physically sit for a portrait. However, for the most part, getting those who do to be candid about their experience has been easy. I think it is a matter of building trust from the very beginning. I show them what I do, and then I tell them very kindly that I want nothing from them other than a bit of their time, and that I am doing this simply to thank them for all that they have done and sacrificed for our country. I am very respectful of how much they want to share. A couple of veterans I photographed didn’t share about their experience—it wasn’t something they were ready to talk about. I talk to them like I’m talking to a friend or neighbor. And it is always all about them. Not me.

Army Air Corps B-17 Gunner Joe Gossen

What have been some common themes amongst the veterans you have met?

I have been impressed that each veteran is very humble about their service in WWII. Even the several veterans I’ve met who have recently traveled back to Europe and the Pacific for high profile anniversaries and ceremonies—being honored by presidents and other dignitaries—and to see where they fought and where their friends died. They often hear people call them heroes, but every one of them will say that they are not a hero, they only did their duty as they were taught—“Duty. Honor. Country”—and that the real heroes are those who didn’t make it back home. They talk more about their fellow soldiers, etc. than they do about themselves. That is impressive in this day now when self-promotion is so rampant. We can learn a lot from the “Greatest Generation.”

Many are willing to talk to groups such as school students about their service in the war because they don’t want it to be forgotten. They also get together with other soldiers of all ages to share and reminisce about their times in the service with those who really understand.

I often ask the veterans what advice they would give to younger generations. The most common answer has been to love one another and to seek and love God. I believe that they realize it was only by God’s grace that they made it through everything that they did.

Army Nurse Lieutenant Beatrice Price

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve learned by working on this project?

One surprise is that most of these 62 plus veterans I’ve met so far, ages 90 to over 102, have very sharp memories of their WWII service. A few forget some dates and names, but overall are spot on with their history.

Another surprising thing is how this whole project has come together for me. It started with one contact. One referral. One veteran just a short drive from my house. I have been blessed with the opportunity and time and resources to do this at just the right time in my life. Even two years ago I probably wouldn’t have been able to do this as effectively as I can now. I feel that God has placed people and experiences in my path at the right time to reach the veterans I am meeting for a purpose. Some of them have even told me that themselves. Now the project is getting recognition on social media and electronic news media. One of my veterans, his wife, and I were interviewed on the local CBS News channel.

I am amazed at the variety of stories I hear from these men (and one woman so far). I’ve met men who survived the attack at Pearl Harbor, fought at Guadalcanal and Okinawa, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, personally knew General Patton, saw Mussolini hanging in the streets of Naples, stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, were surrounded at Bastogne and prevailed, endured the Battle of the Bulge, liberated concentration camps, saw the blast from the second atomic bomb over Japan, shot down enemy aircraft, and were shot down. And I didn’t have to read it in a book—I heard it straight from the source.

Army Air Corps Corporal Howard Polin

Why do you think it’s important for creatives to participate in work like this?

It is creating a legacy. For others, and maybe for yourself. This is a personal project that I love, and the reward is immeasurable. There is just something completely satisfying about using a gift or talent to give back to something bigger than ourselves—to people who deserve it or are in need. I provide free prints and video for the veterans and their families, and I hope that becomes a cherished heirloom for them.

Army PFC Major Wooten

What do you hope that the public takes away from the project?

I hope that people will see the project online and perhaps in other venues like this soon and will realize that there are still WWII veterans out there, but there aren’t many of these living history lessons left. They might be our neighbors. You never know. They don’t talk about themselves much. But when they are invited to talk about it, especially with younger generations, most absolutely love it.

Every veteran has a unique story, and I want people to know what these particular veterans did for our country during WWII through their stories of courage, bravery, service, and leadership. And I want to bring honor to them so that they aren’t forgotten over time.

Army Medic Sargent Ray Lambert

How do veterans get in touch with you if they’re interested in participating?

Veterans or family members and others can reach me through the contact page on my website. I’m grateful that I’m already getting emails from many different states! I need to do a WWII Portraits of Honor tour!

See more incredible portraits of World War II veterans from the Portraits of Honor series.

Army Airborne Sargent Don Minshew

Army Air Corps B-17 Pilot William Massey

Navy veteran Frank Emond

Army Air Corps P-51 Pilot Lieutenant Earl Miller

Army Airborne Sargent James Schmidt

Army PFC Hilman Prestridge

Marine Staff Sargent Welton Hance

Army Tech Harold McMurran

Army Corps Bomber Pilot Lieutenant Colonel John Beard

Army Corporal William Wright

Army PFC Brad Freeman with Jeffrey Rease

Portraits of Honor: Website | Instagram

Jeffrey Rease: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Jeffrey Rease.

Related Articles:

Poignant Portraits of Koreans Separated From Their Loved Ones in the North

Portraits of Soldiers Before, During, and After War

21-Year Old WWII Soldier’s Sketchbooks Reveal a Visual Diary of His Experiences

Newly Discovered 31 Rolls of Film Shot by an Unknown Soldier During WWII