Humans of New York‘s documentary photographer Brandon Stanton has again employed his powerful combination of camera and compassion to raise awareness around a crucial cause. Through a series he shot at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Stanton shares the stories of the wide-ranging lives tragically touched by pediatric cancer. He introduces us to children like Gabe, a third grader who says his rare tumor has taught him how to be brave; to the nurses who tend to the kids as they might their own family; to the parents and siblings who provide steadfast support through the suffering; and to the diligent doctors who dedicate years of their lives to research and treatment.

Stanton describes the poignant personal tales as “war stories,” with the vicious illness demanding a brutal battle for survival. But within the immense agony, Stanton finds precious signs of human strength and altruism, with his subjects' quotations revealing courage, intimacy, grit, and generosity beyond measure. The kids, he says, are “the greatest warriors of all,” but everyone at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center is a war hero in a different way, representing “humanity's bold response to the greatest injustice of nature.”

Stanton's work has not only provided a platform for the pediatric cancer community to speak about their grueling experiences, but also elucidated the dire need for increased funding. Nina Pickett, the Department of Pediatrics Administrator at Memorial Sloan Kettering, explains that federal dollars go mostly towards research on cancers like lung, breast, and colon, while pediatric cancer gets only around four percent of the funds. Stanton hoped to change that statistic, aiming to raise $1 million via this documentary project; but he far surpassed his goal, garnering a whopping $3.8 million via over 100,000 donations in the span of three weeks. Two thirds of the money will go towards the hospital's cancer research, while the rest will provide support for ailing children and families.

Above: “My biggest challenge? Two words for you: third grade. It’s kind of like second grade but harder. I was a very special student in second grade because I had a brain tumor. A very rare one, actually. I was the only one in the world with this type of brain tumor. Everyone who knew me was shocked! Their heads blew up! I’ve been through a lot of things this past year. But I can tell you, if you get brain cancer, try not to worry! It will be very hard and you will get lots of fevers but you have to be brave. You have to be brave like me because I’m very brave about this thing. And if you don’t know how to be brave, I can teach you. I know the surgery seems scary, but I have four words for you: you’ll be on anesthetics. When you wake up, your head will be wrapped like a mummy and your mom will take a picture and show you. When it’s time to get shots, do a countdown from thirty and tell yourself: ‘Calm down, calm down, calm down.’ Then whenever you’re ready, tell the nurse to go. And if you need more time, ask for more time!”

“The absolute best thing in the world that can happen to me is telling a parent that their child’s tumor is benign. I live for those moments. And the worst thing that can happen to me is telling a parent that I’ve lost their kid. It’s only happened to me five times in thirty years. And I’ve wanted to kill myself every single time. Those parents trusted me with their child. It’s a sacred trust and the ultimate responsibility is always mine. I lose sleep for days. I second-guess every decision I made. And every time I lose a child, I tell the parents: ‘I’d rather be dead than her.’ And I mean it. But I go to church every single day. And I think that I’m going to see those kids in a better place. And I’m going to tell them that I’m sorry. And hopefully they’ll say, ‘Forget it. Come on in.’ ”

“The absolute best thing in the world that can happen to me is telling a parent that their child’s tumor is benign. I live for those moments. And the worst thing that can happen to me is telling a parent that I’ve lost their kid. It’s only happened to me five times in thirty years. And I’ve wanted to kill myself every single time. Those parents trusted me with their child. It’s a sacred trust and the ultimate responsibility is always mine. I lose sleep for days. I second-guess every decision I made. And every time I lose a child, I tell the parents: ‘I’d rather be dead than her.’ And I mean it. But I go to church every single day. And I think that I’m going to see those kids in a better place. And I’m going to tell them that I’m sorry. And hopefully they’ll say, ‘Forget it. Come on in.’ ”

“The MDs build the treatment plan. The nurse’s job is to get it done. We’re the ones who are always there, making sure every single moment of every single day is the best it can possibly be. What’s going to take away that nausea? What’s going to take away that pain? How can we convince the doctor to let this kid see some sunshine? We know when the kid has a play at school. We know which massage therapist they love and which member of the family is most likely to persuade them to take their medicine. These kids rely on certain nurses like they’re gold. A lot of time these kids won’t listen to the doctor. But they’ll listen to their nurse.”

“The MDs build the treatment plan. The nurse’s job is to get it done. We’re the ones who are always there, making sure every single moment of every single day is the best it can possibly be. What’s going to take away that nausea? What’s going to take away that pain? How can we convince the doctor to let this kid see some sunshine? We know when the kid has a play at school. We know which massage therapist they love and which member of the family is most likely to persuade them to take their medicine. These kids rely on certain nurses like they’re gold. A lot of time these kids won’t listen to the doctor. But they’ll listen to their nurse.”

“We’ve been fighting this for thirteen years. Sterling has a brain tumor in the center of his brain where the optic nerves cross. It’s inoperable. Our lives center around keeping the tumor from growing. That’s what we do. We’re here today to pick up a new experimental medicine. Sterling’s had over one thousand seizures. I joke that this whole experience has made me an involuntary Buddhist. When you live in a world of one thousand seizures, you have no choice but to live in the present. You’re jolted out of your mind every few minutes. And you learn about compassion. Having a special needs child has opened me up to the compassion of other people. There are so many people who are willing to help. When we first discovered the tumor, I sent Sterling’s scans to every hospital. I can’t tell you how many doctors gave me their time and didn’t charge a thing. Zero billable hours. Can you believe it? It was like going snorkeling for the first time, and discovering a whole new world of color that I didn’t know existed.”

“We’ve been fighting this for thirteen years. Sterling has a brain tumor in the center of his brain where the optic nerves cross. It’s inoperable. Our lives center around keeping the tumor from growing. That’s what we do. We’re here today to pick up a new experimental medicine. Sterling’s had over one thousand seizures. I joke that this whole experience has made me an involuntary Buddhist. When you live in a world of one thousand seizures, you have no choice but to live in the present. You’re jolted out of your mind every few minutes. And you learn about compassion. Having a special needs child has opened me up to the compassion of other people. There are so many people who are willing to help. When we first discovered the tumor, I sent Sterling’s scans to every hospital. I can’t tell you how many doctors gave me their time and didn’t charge a thing. Zero billable hours. Can you believe it? It was like going snorkeling for the first time, and discovering a whole new world of color that I didn’t know existed.”

“I grew up around nature. I had a wonderful family and a great life and it was so easy to be a believer. Then over the course of a single weekend, I learned that my one-year-old son was blind, had a seizure disorder, and a brain tumor. I remember I went to a beach, and a storm was coming in, and I just sat on the edge of the ocean and I wailed. For an hour I screamed in the pouring rain. That was thirteen years ago, and there hasn’t been a moment of relaxation since then. We’ve researched everything. We’ve tried everything. Anything to keep the tumor from growing. And the longer we’ve gone on, the more we’ve tried, and the narrower the choices get. There is nothing I won’t do to save my child. There is not a doctor you can keep me from. I’ll drive across the country for a single conversation. But I live with such pain. It’s not rocket science. Every day could be the day that I lose my child. But I’m trying to look up. I’m trying to have gratitude. And I’m trying to keep my faith.”

“I grew up around nature. I had a wonderful family and a great life and it was so easy to be a believer. Then over the course of a single weekend, I learned that my one-year-old son was blind, had a seizure disorder, and a brain tumor. I remember I went to a beach, and a storm was coming in, and I just sat on the edge of the ocean and I wailed. For an hour I screamed in the pouring rain. That was thirteen years ago, and there hasn’t been a moment of relaxation since then. We’ve researched everything. We’ve tried everything. Anything to keep the tumor from growing. And the longer we’ve gone on, the more we’ve tried, and the narrower the choices get. There is nothing I won’t do to save my child. There is not a doctor you can keep me from. I’ll drive across the country for a single conversation. But I live with such pain. It’s not rocket science. Every day could be the day that I lose my child. But I’m trying to look up. I’m trying to have gratitude. And I’m trying to keep my faith.”

“You have to have faith and keep working. Back in the 70’s and 80’s, all of us were hoping for just a single survivor of stage four neuroblastoma. It was a rare cancer and we just couldn’t cure it. But eventually we figured it out. Recently over five hundred people attended a party we threw for neuroblastoma survivors. So change does happen. It just happens slowly. I have a colleague who lost hope recently. He’s been working on a brain tumor called DIPG, and he’s had nothing but three decades of negative outcomes. Dozens and dozens of failed trials. We just couldn’t touch the tumor because it’s in the main center of the brain. But my colleague stayed optimistic. He kept cheering us on. But he finally lost hope. After three decades of losing kids, he asked to not see any more DIPG patients. Then guess what happened. We finally have a survivor on our hands. Our neurosurgeon Dr. Souweidane figured out how to insert a catheter directly into the tumor. And we now have a girl that is 3.5 years from diagnosis. It’s still early, but it’s promising. She plays tennis. She plays violin. And she is gorgeous.”

“You have to have faith and keep working. Back in the 70’s and 80’s, all of us were hoping for just a single survivor of stage four neuroblastoma. It was a rare cancer and we just couldn’t cure it. But eventually we figured it out. Recently over five hundred people attended a party we threw for neuroblastoma survivors. So change does happen. It just happens slowly. I have a colleague who lost hope recently. He’s been working on a brain tumor called DIPG, and he’s had nothing but three decades of negative outcomes. Dozens and dozens of failed trials. We just couldn’t touch the tumor because it’s in the main center of the brain. But my colleague stayed optimistic. He kept cheering us on. But he finally lost hope. After three decades of losing kids, he asked to not see any more DIPG patients. Then guess what happened. We finally have a survivor on our hands. Our neurosurgeon Dr. Souweidane figured out how to insert a catheter directly into the tumor. And we now have a girl that is 3.5 years from diagnosis. It’s still early, but it’s promising. She plays tennis. She plays violin. And she is gorgeous.”

“I got cancer in the summer when the pools were opening. And I really wanted to go swimming but I couldn’t leave the hospital. I begged her not to go swimming without me. And she didn’t because I couldn’t.”

“I got cancer in the summer when the pools were opening. And I really wanted to go swimming but I couldn’t leave the hospital. I begged her not to go swimming without me. And she didn’t because I couldn’t.”

“I got diagnosed last January. A mass behind my spine, two masses in my lungs, spots all over my lymph nodes and bone marrow. The guy who gave me the CT scan threw up afterward. The doctor said they could guarantee three years. I was like: ‘Three years. Holy shit.’ My biggest worry is that I’m going to die and not do all the things I wanted to do. The funny thing is—I didn’t even realize how many things I wanted to do until I got diagnosed. Simple things like meeting a guy, getting married, getting a job, having my own apartment, and even picking out my own furniture. Those never seemed too interesting to me. They just seemed like adult things that were guaranteed to happen. Now I want to do them so bad. Because I want to know what they feel like.”

“I got diagnosed last January. A mass behind my spine, two masses in my lungs, spots all over my lymph nodes and bone marrow. The guy who gave me the CT scan threw up afterward. The doctor said they could guarantee three years. I was like: ‘Three years. Holy shit.’ My biggest worry is that I’m going to die and not do all the things I wanted to do. The funny thing is—I didn’t even realize how many things I wanted to do until I got diagnosed. Simple things like meeting a guy, getting married, getting a job, having my own apartment, and even picking out my own furniture. Those never seemed too interesting to me. They just seemed like adult things that were guaranteed to happen. Now I want to do them so bad. Because I want to know what they feel like.”

“Some of my colleagues tell me they can’t imagine working in pediatrics. Millions of years of evolution have conditioned us to respond to the cries of a child. We can’t bear to see a child in pain. And once we have children of our own, it makes the work even more difficult. We all handle it differently, but everyone cries at some point. Not in front of the patient, but everyone cries. Every few months we have a ceremony where we mourn all the children who have passed away. We have a slideshow. We make cards. We talk about them and remember them together. We acknowledge that we all feel the loss. And even though our grief is not as significant as the family’s, it’s not trivial either. And we must take time to acknowledge that. Or all of us will burn out.”

“Some of my colleagues tell me they can’t imagine working in pediatrics. Millions of years of evolution have conditioned us to respond to the cries of a child. We can’t bear to see a child in pain. And once we have children of our own, it makes the work even more difficult. We all handle it differently, but everyone cries at some point. Not in front of the patient, but everyone cries. Every few months we have a ceremony where we mourn all the children who have passed away. We have a slideshow. We make cards. We talk about them and remember them together. We acknowledge that we all feel the loss. And even though our grief is not as significant as the family’s, it’s not trivial either. And we must take time to acknowledge that. Or all of us will burn out.”

“I feel like it’s draining us. Both emotionally and physically. Her immune system is so depleted that if she gets sick, it could kill her. So I’m afraid all the time. And that fear tends to keep me on the attack. I can be short tempered with my husband and my boys. I feel like if I scream, everyone will stay away from her and she’ll be OK. My husband and I have been fighting a lot. We’ll snap at each other over little things like the chores or giving her medicine. Before the diagnosis, we were always sure to talk things out before bed. But now we’re both so stressed that we hold stuff in. He doesn’t know how I’ll react. And I don’t know how he’ll react. So we just choose not to discuss our problems. This Saturday we went on our first date since the diagnosis. It was only two hours at an Italian restaurant, but it was nice to finally talk. We acknowledged that we’ve been on edge. And we apologized to each other.”

“I feel like it’s draining us. Both emotionally and physically. Her immune system is so depleted that if she gets sick, it could kill her. So I’m afraid all the time. And that fear tends to keep me on the attack. I can be short tempered with my husband and my boys. I feel like if I scream, everyone will stay away from her and she’ll be OK. My husband and I have been fighting a lot. We’ll snap at each other over little things like the chores or giving her medicine. Before the diagnosis, we were always sure to talk things out before bed. But now we’re both so stressed that we hold stuff in. He doesn’t know how I’ll react. And I don’t know how he’ll react. So we just choose not to discuss our problems. This Saturday we went on our first date since the diagnosis. It was only two hours at an Italian restaurant, but it was nice to finally talk. We acknowledged that we’ve been on edge. And we apologized to each other.”

“If there’s a chance then it’s worth a try. Even if nobody else wants to try, I will try. A lot of these kids have exhausted all their options. They may have had several surgeries elsewhere and it’s either hospice or one more try. My colleagues are amazing. So I know that if I can get this lump out, the child has a chance. I view each of these kids as my own. My team is amazing but I take 100% responsibility for the outcome and I don’t like to lose a drop of blood. So it’s a lot of stress. I have four grafts in my heart. My neck muscles are always tense. Some of these surgeries have probably taken years off my life. But tumors kill kids in very horrible ways. So if there’s a chance, I will try.”

“If there’s a chance then it’s worth a try. Even if nobody else wants to try, I will try. A lot of these kids have exhausted all their options. They may have had several surgeries elsewhere and it’s either hospice or one more try. My colleagues are amazing. So I know that if I can get this lump out, the child has a chance. I view each of these kids as my own. My team is amazing but I take 100% responsibility for the outcome and I don’t like to lose a drop of blood. So it’s a lot of stress. I have four grafts in my heart. My neck muscles are always tense. Some of these surgeries have probably taken years off my life. But tumors kill kids in very horrible ways. So if there’s a chance, I will try.”

“Whenever I saw my parents sad, it always made me a little more nervous. Like when I asked my mom how long it would be until I could eat again. And I said: ‘Ten years?’ And she shook her head and said, ‘Not that long.’ Then I said, ‘Five years?’ And she started crying. I do feel sorry for them. They are the best parents in the world and it’s very hard for them. You know, me not being quite who I used to be. I don’t have my full voice back. I haven’t done much physical activity in the last two years. They were always very proud of me. I think they’re still proud of me now but for different reasons. A lot of adults tell me that I’m more mature than a lot of eighteen year olds. Because I know that life isn’t just happy times, and now I know how to handle it.”

“Whenever I saw my parents sad, it always made me a little more nervous. Like when I asked my mom how long it would be until I could eat again. And I said: ‘Ten years?’ And she shook her head and said, ‘Not that long.’ Then I said, ‘Five years?’ And she started crying. I do feel sorry for them. They are the best parents in the world and it’s very hard for them. You know, me not being quite who I used to be. I don’t have my full voice back. I haven’t done much physical activity in the last two years. They were always very proud of me. I think they’re still proud of me now but for different reasons. A lot of adults tell me that I’m more mature than a lot of eighteen year olds. Because I know that life isn’t just happy times, and now I know how to handle it.”

“I think I have post traumatic stress. I have so many horrible flashbacks. Two weeks after Max was diagnosed, he asked me if I’d be his Mommy forever. I said, ‘Of course I will.’ And he asked: ‘Even when I’m ninety?’ And I told him ‘yes.’ What was I supposed to say? And there were all the times he talked to me about the future. We’d talk about college. I just couldn’t tell him. God I was such a coward. I should have told him. I just couldn’t do it. Even toward the end. The day before he lost consciousness, I read his favorite book to him. It’s called Runaway Bunny. And the little bunny keeps threatening to run away. And the Mama bunny keeps saying: ‘Wherever you go, I will find you.’ Oh God, it was such a horrible way to die. He couldn’t speak or move or swallow or see. He basically starved to death. And the whole last week I’m whispering in his ear: ‘Let go, let go. Please Max, let go.’ My seven-year-old son. I’m telling him to let go. I mean, f*ck. That’s not supposed to happen! And the whole time I never told him he was dying. I was such a coward. But he knew. He knew without me telling him. Because a couple weeks before he lost his speech, he asked me: ‘Mommy, do they speak English where I’m going?’ ”

“I think I have post traumatic stress. I have so many horrible flashbacks. Two weeks after Max was diagnosed, he asked me if I’d be his Mommy forever. I said, ‘Of course I will.’ And he asked: ‘Even when I’m ninety?’ And I told him ‘yes.’ What was I supposed to say? And there were all the times he talked to me about the future. We’d talk about college. I just couldn’t tell him. God I was such a coward. I should have told him. I just couldn’t do it. Even toward the end. The day before he lost consciousness, I read his favorite book to him. It’s called Runaway Bunny. And the little bunny keeps threatening to run away. And the Mama bunny keeps saying: ‘Wherever you go, I will find you.’ Oh God, it was such a horrible way to die. He couldn’t speak or move or swallow or see. He basically starved to death. And the whole last week I’m whispering in his ear: ‘Let go, let go. Please Max, let go.’ My seven-year-old son. I’m telling him to let go. I mean, f*ck. That’s not supposed to happen! And the whole time I never told him he was dying. I was such a coward. But he knew. He knew without me telling him. Because a couple weeks before he lost his speech, he asked me: ‘Mommy, do they speak English where I’m going?’ ”

“I’ve been on a mission for seventeen years. It’s my holy grail. I’m trying to cure a brain tumor called DIPG that kills 100 percent of the children who have it. It only affects 200 kids a year so it’s never gotten much attention. But if you saw a child die from DIPG, you’d understand why I care so much. It’s awful. It’s just awful. Parents come to me in droves asking me to help. They say: ‘This can’t happen. Please do something.’ But there’s nothing I can do. Their child will be dead in a year. It’s horrible. It’s been a very tough thing to care about. I didn’t get into neurosurgery to watch kids die. I chose this job to heal people. And DIPG has been seventeen years of watching kids die. It’s a very dark place to work. But if I can find a cure, so much of that pain will be paid back in a single instant. And on that day I will feel like there has been some justice.”

“I’ve been on a mission for seventeen years. It’s my holy grail. I’m trying to cure a brain tumor called DIPG that kills 100 percent of the children who have it. It only affects 200 kids a year so it’s never gotten much attention. But if you saw a child die from DIPG, you’d understand why I care so much. It’s awful. It’s just awful. Parents come to me in droves asking me to help. They say: ‘This can’t happen. Please do something.’ But there’s nothing I can do. Their child will be dead in a year. It’s horrible. It’s been a very tough thing to care about. I didn’t get into neurosurgery to watch kids die. I chose this job to heal people. And DIPG has been seventeen years of watching kids die. It’s a very dark place to work. But if I can find a cure, so much of that pain will be paid back in a single instant. And on that day I will feel like there has been some justice.”

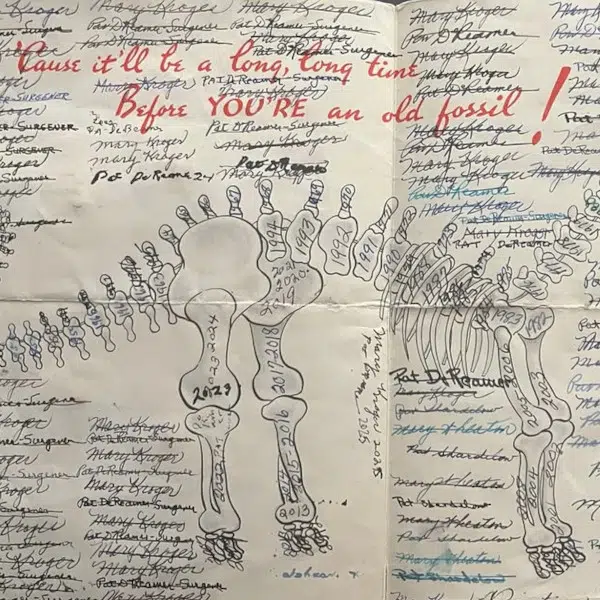

“These are my beads of courage. You get a yellow bead for an overnight stay. A white bead is for chemo. A black bead is when you get pricked. And I have two special heart-shaped beads because my heart stopped twice. The first time my heart stopped was late at night. It started beating really fast, and my nurse got very scared, and suddenly ten doctors ran in. They pulled out a big bag of ice and put it on my chest. I was a little annoyed because Justin Bieber was performing at the VMA’s and I had to turn down the volume. The doctors said, ‘Grace have you ever been on a roller coaster? This medicine is going to make you feel like you’re going down a giant hill!’ And they started putting those shock paddles on me. And I heard them tell my mom they were going to stop my heart, and she took out her Valium and started chewing it so it would work faster. Then somebody screamed, ‘Everyone clear!’ And my Mom said: ‘Are you ready Grace? It’s just a roller coaster! Are you ready?’ And then they pushed the shot into my IV and it felt like the world stopped spinning. The machine was going ‘beep, beep, beep,’ but then it stopped. And then nothing. And then nothing. And it felt like a giant boulder was dropped on my chest. And then suddenly my heart started beating again. And I yelled: ‘That did not feel like a roller coaster!’ ”

“These are my beads of courage. You get a yellow bead for an overnight stay. A white bead is for chemo. A black bead is when you get pricked. And I have two special heart-shaped beads because my heart stopped twice. The first time my heart stopped was late at night. It started beating really fast, and my nurse got very scared, and suddenly ten doctors ran in. They pulled out a big bag of ice and put it on my chest. I was a little annoyed because Justin Bieber was performing at the VMA’s and I had to turn down the volume. The doctors said, ‘Grace have you ever been on a roller coaster? This medicine is going to make you feel like you’re going down a giant hill!’ And they started putting those shock paddles on me. And I heard them tell my mom they were going to stop my heart, and she took out her Valium and started chewing it so it would work faster. Then somebody screamed, ‘Everyone clear!’ And my Mom said: ‘Are you ready Grace? It’s just a roller coaster! Are you ready?’ And then they pushed the shot into my IV and it felt like the world stopped spinning. The machine was going ‘beep, beep, beep,’ but then it stopped. And then nothing. And then nothing. And it felt like a giant boulder was dropped on my chest. And then suddenly my heart started beating again. And I yelled: ‘That did not feel like a roller coaster!’ ”

Humans of New York: Website | Facebook | Instagram

via [Huffington Post, Today]

All images via Brandon Stanton.