Photo: Stock Photos from Tupungato/Shutterstock

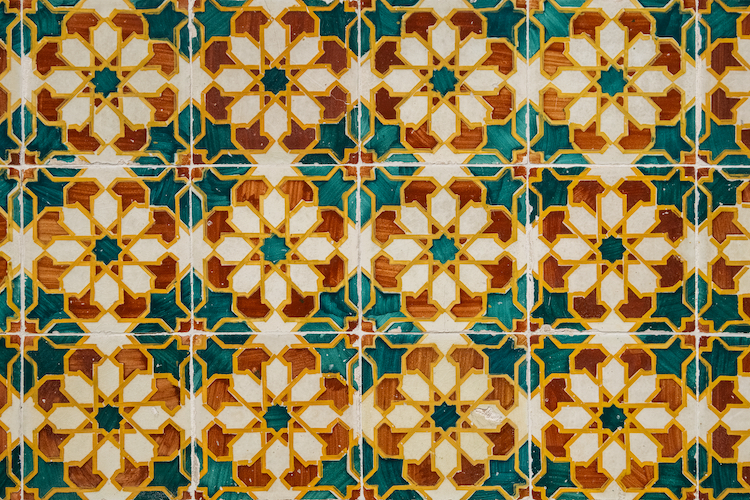

If you’ve ever visited or seen pictures of the gorgeous cities of Portugal, you’ve likely noticed the exquisitely painted tiles that adorn the buildings’ façades. These luminous and captivating embellishments are called azulejos, and they are one of the most distinctive features of urban Portuguese architecture and design. Gracing the exterior as well as the interior of many edifices, they serve as both a functional and beautifying addition to each city’s landscape.

Though azulejos did not originate in Portugal, it is there that the craft has truly blossomed and remains alive still to this day. Coming from origins of a purely decorative function, the tiles have evolved into an art form of their own. And as they have been adapted and evolved there over the centuries, they’ve become one of the most iconic aspects of the country’s history, architecture, and culture.

Photo: Stock Photos from Andrei Nekrassov/Shutterstock

The Origins of Azulejos in Europe

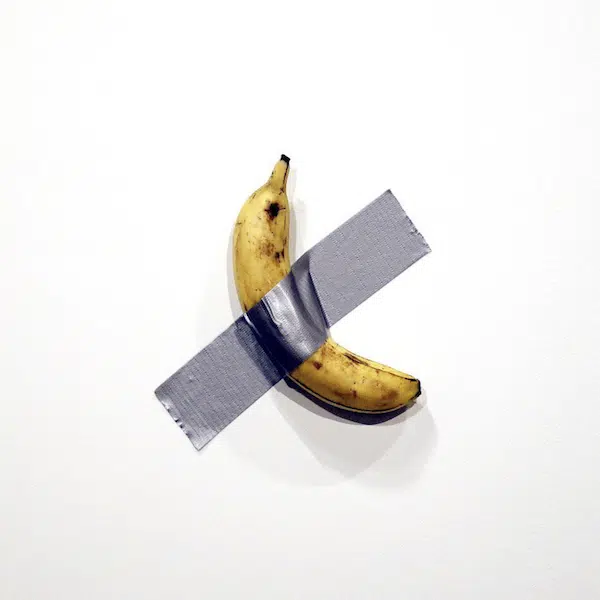

Though the first known glazed tiles originated in the regions of Egypt and Mesopotamia during the 27th century BCE, it wasn’t until the 13th century CE that the technique was introduced to the Iberian Peninsula by way of the Moors from the Middle East. The craft was originally developed to imitate Byzantine and Roman mosaics, and it is for that reason that the tiles are called azulejos—a word derived from the Arabic word “zellige,” which means polished stone. Some of the earliest productions of tile in Europe began in Seville, Spain—where the tiles were glazed and cut into smaller pieces then reassembled to form geometric patterns.

Portuguese king Manuel I fell in love with this technique after a visit to Seville in 1503, and he later introduced the craft to his home country. Azulejos were used extensively in the Sintra National Palace—just outside of Lisbon—and from there, the Portuguese love affair with azulejos only grew. This was so much so that they even adopted the Moorish tradition of horror vacui (or the fear of empty space) and began to cover walls completely with the glazed tiles.

The Portuguese use of azulejos evolved dramatically throughout the years, and each region of the country developed its own unique and characteristic way of glazing and using the tiles. Though azulejos came to Europe primarily as an artisanal discipline, in Portugal, it developed into a high art form in its own right.

Interior of the Sintra National Palace (Photo: Stock Photos from Sopotnicki/Shutterstock)

The Evolution of Portuguese Tiles

During the early to mid 16th century, the Portuguese mainly relied on foreign imports of tile from Seville in the south, and on a smaller scale from Antwerp in the north. It was during this time that potters from Italy had established workshops in Seville, and they brought with them the maiolica techniques—a form of tin-glazing pottery that allowed them to represent more varied and figurative subjects and themes on their tile compositions—and also the influence of the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist styles.

This development in the technique sparked a shift from solely repetitious patterns and elevated it into a form of artistic creation where the tile was painted on as if it were a wood panel or canvas. Consequently, most of the tiles began to depict allegorical and mythological portrayals of the lives of saints and scenes from the Bible as well as hunting scenes. Now, instead of craftsmen creating repetitive patterns with the tiles, artists were painting them as large-scale panels and signing their names to the creations.

Cloister Walls of Porto Cathedral (Photo: Stock Photos from Vladimir Korostyshevskiy/Shutterstock)

In the latter part of the 16th century, azulejos started to be used to decorate large empty spaces, such as those in churches and monasteries, and also as decoration for the front of the church altars. It started with plain diagonal tiles, which were then replaced with horizontal polychrome tiles—usually displaying interweaving patterns and motifs of flowers and garlands—in the 17th century. These tiles were often the border to small votive scenes from the life of Christ or one of the saints. Arrangements such as these began to be known as “azulejo de tapete” or carpet compositions because of the inspiration from the rich colors and patterns from fabrics and carpets imported from the East.

At the end of the 17th century, the Dutch began to produce monochromatic blue and white tiles, imitating the much-coveted style of Chinese porcelain. This variety of azulejos became extremely popular among Portuguese aristocrats, and they began to commission them in great numbers to decorate their palaces and churches. Portuguese tile painters also began to copy the technique, and after King Peter II put a stop to all imports of azulejos from 1687 to 1698, they soon only used tiles produced, designed, and painted by Portuguese artists. The blue and white style had become the most dominant trend, and this is quite apparent in its overwhelming presence all over the country today.

Azulejo Panels in the Gardens of the Fronteira Palace in Lisbon (Photo: Stock Photos from WorldPhotosadanijs/Shutterstock)

In Portugal, the late 17th and early 18th centuries became known as the “Ciclo dos Mestros” or the Cycle of Masters—also known as the Golden Age of the Azulejo. During that time, they began to produce tiles en mass, due in large part to an increase in demand within the country as well as from Brazil (then a Portuguese colony). The styles and motifs employed in tile painting continued to change as they were influenced by the ornate Baroque and more delicately ornamental Rococo styles.

After the destruction of the great earthquake of 1755 and the subsequent reconstruction of Lisbon, the use of azulejos began to take on a more functional role, which spurred a return to simpler designs and motifs. This became known as the Pombaline style—after the Marquis of Pombal, who had been put in charge of the rebuilding efforts.

Photo: Stock Photos from Dace Kundrate/Shutterstock

In the 19th and 20th centuries, azulejos continued to evolve under the influence of prevalent art movements of the time. In the 19th century, there arose a transition to a more subdued Neoclassical style, which was also accompanied by industrialized methods of producing simple stylized designs. During the 20th century is when the prominent Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles began to influence the style of Portuguese azulejos.

During the 20th century, the work of several artists sparked a seeming revival and contemporary update to the traditional art of the azulejo. The art form even expanded from just gracing the façades of buildings above ground to adorning the walls of the Lisbon Underground. Several contemporary artists throughout the 70s and 80s were commissioned to create azulejo panels decorating each unique subway station throughout the city.

Azulejo Mural by Erró in Oriente Metro Station, Lisbon (Photo: Stock Photos from Marina J/Shutterstock)

Azulejos within Portugal's Contemporary Cultural Landscape

Today, the art of the azulejo is still alive and well in Portugal. There are several of the original factories from the 17th and 18th centuries that are still in operation today, duplicating traditional styles of years past as well as creating new ones. And artists continue to express themselves in various forms by way of this incredibly versatile medium.

In order to preserve the Portuguese history and heritage of this incredible art, the Museo Nacional do Azulejo (National Museum of the Azulejo) was established in 1965. And because of their popularity and natural vulnerability to theft and vandalism, as well as neglect, the country’s azulejos are under several protective laws enacted by the national government. There are also many protection and preservation groups that occupy themselves with the issue of maintaining this important part of Portuguese cultural inheritance.

If you ever get the chance to visit Portugal, take the time to truly look at your surroundings and absorb the ever-changing historic tapestry—wrought in painted tiles—that surrounds you. Maybe even participate in a workshop to learn some of the traditional techniques yourself and take the finished product home as a souvenir. The centuries-old art form is truly an incredible mode of artistic expression that has come to define the spirit of the country. It’s definitely something you’ve got to see!

Photo: Stock Photos from karnavalfoto/Shutterstock