Harmonia Rosales, “Portrait of Eve,” 2021. (Photo: Brad Kaye)

Across millennia, there have been several common threads that unite humanity, whether it be art, music, or literature. Now, the Getty presents yet another commonality: creation myths. Such narratives are at the heart of the museum’s newest exhibition, Beginnings: The Story of Creation in the Middle Ages, which explores how medieval Christians understood and visualized the world’s origins.

At first glance, Beginnings may seem familiar. The exhibition gathers several works inspired by the Bible, ranging from the story of Adam and Eve to the seven days of creation. But Getty curators Elizabeth Morrison and Larisa Grollemond wanted to propel these recognizable themes into our modern world, complicating their legacy and art historical status. What better way to do so, the duo thought, than by inviting a contemporary artist into the fold?

To Morrison and Grollemond, Harmonia Rosales felt like a natural addition to Beginnings. In the exhibition, the artist presents canvases that reimagine Middle Age creation myths through the lens of West African Yoruba mythology and Black resilience, offering a more nuanced interpretation of the world’s genesis. Portrait of Eve, for instance, reimagines the traditional Christian Eve by placing her within a circular ori, a decorated halo-like shape that symbolizes destiny and spiritual transformation. Surrounding Eve is a series of golden roundels, containing scenes that depict the tribulations of her descendants in America. Taken together, the portrait positions Eve not just as a primordial ancestor, but as a figure capable of interrupting intergenerational cycles of trauma.

“Reimagining creation through Yoruba cosmology is less about introducing something foreign and more about restoring what was deliberately obscured,” Rosales tells My Modern Met. “These myths carry systems of balance, accountability, and reverence for life that feel especially necessary in this moment.”

Morrison and Grollemond echo the sentiment: “Including contemporary art with a fresh viewpoint alongside works from our collection allows us to expand the perspectives and kinds of narratives in the gallery for a diverse public audience.”

My Modern Met had the chance to speak with artist Harmonia Rosales as well as curators Elizabeth Morrison and Larisa Grollemond about Beginnings, origin myths, and resurrecting these timeless stories in our contemporary context.

Detail, “The Creation of the Sun and the Moon“ from the “Historical Bible,” about 1360-70, Master of Jean de Mandeville.

What was the process of curating Beginnings, and what do you hope audiences will take away from it?

Elizabeth Morrison and Larisa Grollemond [EM/LG]: We approached Beginnings with our permanent collection in mind, and we knew there was a wealth of images to choose from that represented the Christian Creation in the Biblical book of Genesis. From there, it was a natural choice to expand outward and examine images of Adam and Eve more closely as well as to include a small section on Creation as it was conceived of in Hebrew and Islamic books.

Because we knew we wanted to include works by Harmonia Rosales that also address issues around the story of Creation, we kept the number of manuscripts on view relatively small to encourage dialogue between the medieval illuminations and the contemporary paintings.

“The Creation of the World” from the “Stammheim Missal,” probably 1170s German. (Photo: Getty Museum)

Why did it feel important to incorporate a contemporary voice within the exhibition?

[EM/LG]: Like many collections of historical European art, ours is heavily weighted towards depictions of white Christians. Including contemporary art with a fresh viewpoint alongside works from our collection allows us to expand the perspectives and kinds of narratives in the gallery for a diverse public audience. It enlivens the interpretation of the medieval work and casts both the medieval and the contemporary in a different light, each working to add a layer of meaning to the other. Our visitors have really enjoyed this kind of presentation in the past, so we wanted to build on that diachronic approach with this exhibition.

“The Creation of the World” from the Bible, 1637-38, Malnazar and Aghap‘ir. (Photo: Getty Museum)

What was it like to collaborate with Harmonia Rosales?

[EM/LG]: We first met Harmonia a few years ago after finding her work online and immediately being drawn to it. We’ve had a lively dialogue since then about the relationships between her approach to composition and content as well as her artistic techniques and the medieval and Renaissance paintings that she uses as inspiration.

The collaboration has been fruitful: having her images of Adam and Eve in mind led us to choose certain images from the collection to have on view, and when we showed her the Creation image in the Stammheim Missal, which is the centerpiece of the exhibition, she was inspired to create a new work, which is also featured in the exhibition.

“The Creation of the Sun and the Moon“ from the “Historical Bible,” about 1360-70, Master of Jean de Mandeville. (Photo: Getty Museum)

How did you tackle the project of reimagining creation myths from the Middle Ages? Was there anything particularly challenging about that process?

Harmonia Rosales [HR]: I approached the project by working from creation stories that have always existed for me, narratives I’ve lived with rather than ones I needed to invent. The greatest challenge—and one I didn’t fully anticipate—was finding a visual language capable of holding ideas that are vast, layered, and cosmological while still remaining immediately legible. Creation myths are dense by nature. That density is precisely what draws me to medieval iconography: it has a way of distilling the infinite into clear symbols, making the incomprehensible feel graspable without flattening its meaning.

Harmonia Rosales, “Creation,” 2025. (Photo: Elon Schoenholz)

Does it feel timely or significant to reimagine these myths at this moment in time, especially through the lens of West African Yoruba mythology and Black resilience?

[HR]: It absolutely feels timely, though not because these stories are new. What feels urgent is the need to remember that other ways of understanding the world have always existed alongside the dominant narratives we’ve been taught in schools or in popular culture. Reimagining creation through Yoruba cosmology is less about introducing something foreign and more about restoring what was deliberately obscured. These myths carry systems of balance, accountability, and reverence for life that feel especially necessary in this moment. They remind us that creation is not singular, and that knowledge—like resilience—has many origins.

“The Fall of the Rebel Angels” from “Book of Good Manners,” about 1430. (Photo: Getty Museum)

How do these contemporary reinterpretations contrast and/or complement those featured in the exhibition?

[HR]: I see my work less as a contrast and more as a continuation within a long lineage of image-making. The medieval works in the exhibition were doing the same thing I’m doing now: using the visual language of their time to make sense of origin, divinity, and humanity. Where we differ is not in intention, but in perspective. Those works reflect a worldview that eventually became dominant, while my reinterpretations widen the frame by reintroducing creation stories that were pushed outside the canon. Seen together, the works reveal how mythology is shaped by power, geography, and access; and how visual culture has always played a role in determining which truths endure.

[EM/LG]: Harmonia’s work has obvious aesthetic connections with the medieval work in the gallery, and it reinterprets some of the familiar Christian iconography, but it offers a critical reassessment and even a subversion of it, synthesizing West African Yoruba stories with traditional Christian narratives and centering Black figures. We hope to challenge visitors to reconceptualize stories about the Creation and see both history and the world around them in a new way.

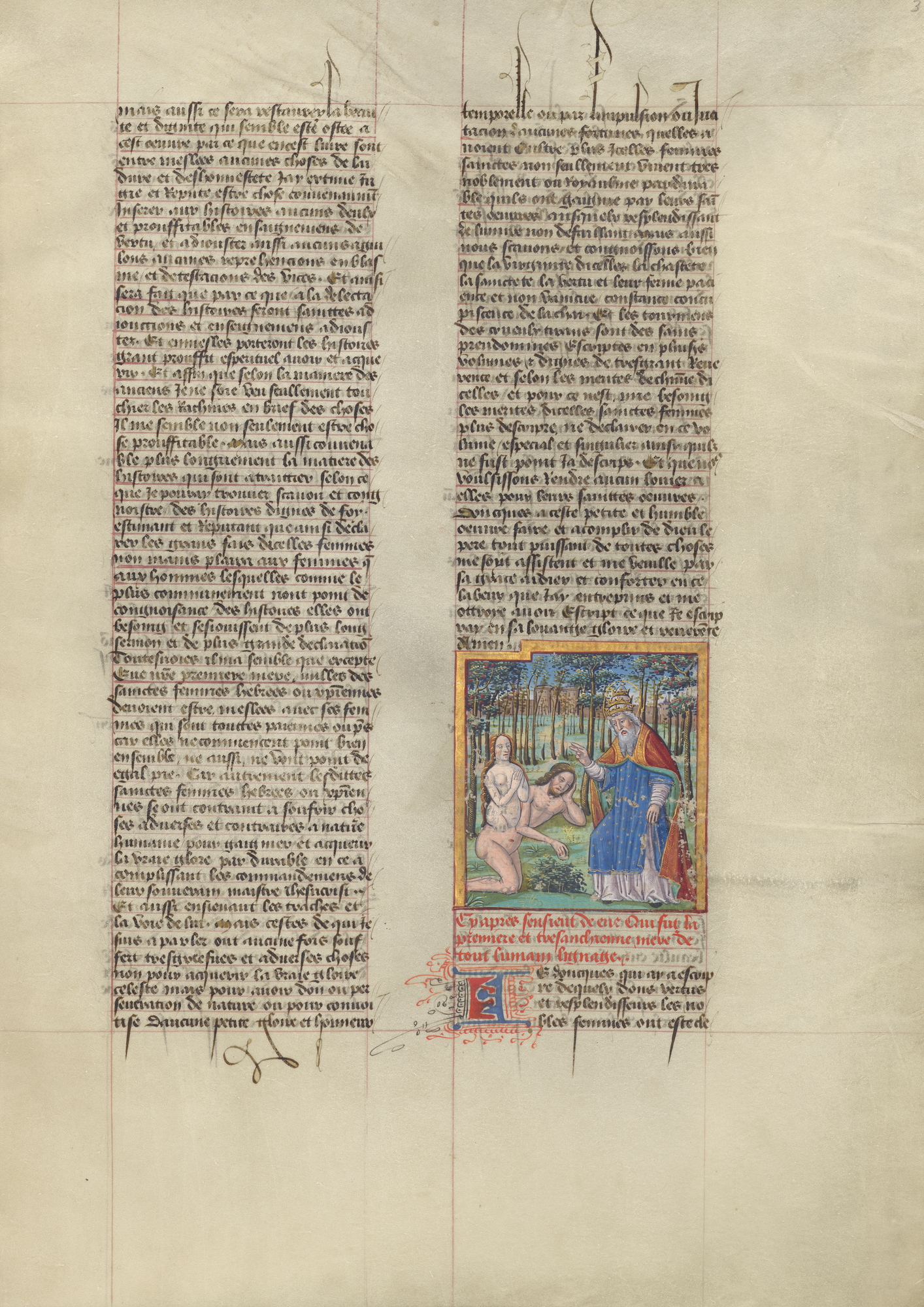

“The Creation of Eve” from “Concerning Famous Women,” written about 1470, illuminated about 1515-20. Étienne Colaud, artist, and Giovanni Boccaccio, author. (Photo: Getty Museum)

What do you hope that people will take away from your contributions to the exhibition?

[HR]: I hope people leave with a sense that creation is not a fixed story, but a living one, shaped by who is telling it and who has been allowed to be seen. My aim isn’t for viewers to replace one belief with another, but to recognize how much has been omitted from what we often accept as universal knowledge. If the work opens space for curiosity and a deeper understanding that multiple truths can coexist, then it has done its job. Ultimately, I want the work to remind people that imagination itself is a form of inheritance, and that reclaiming it is an act of both remembrance and possibility. I also always want people to feel seen by the work. To remember that all stories belong in museums.

[EM/LG]: We always hope that our exhibitions will encourage audiences to look critically and think about the legacy of the medieval in the contemporary world. Creation stories are so universal, we wanted to encourage viewers to think about how origin stories from the past and the present impact their understanding of the world.

Detail from “The Creation of Eve” from “Concerning Famous Women,” written about 1470, illuminated about 1515-20. (Photo: Getty Museum)

Exhibition Information:

Beginnings: The Story of Creation in the Middle Ages

January 27–April 19, 2026

Getty Center

1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90049

Harmonia Rosales: Website

Getty Center: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by the Getty Center.

Related Articles:

New Exhibition Contends With Black Heritage Through Layered, Evocative Textile Art

Exhibition Meditates Upon How Women and Nature Converge Through Painting and Sculpture

New Exhibition Celebrates the Joy, Beauty, and Necessity of Dancehalls