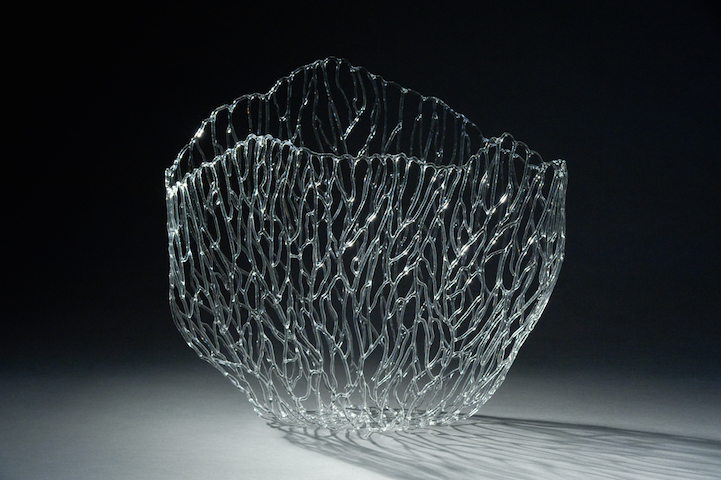

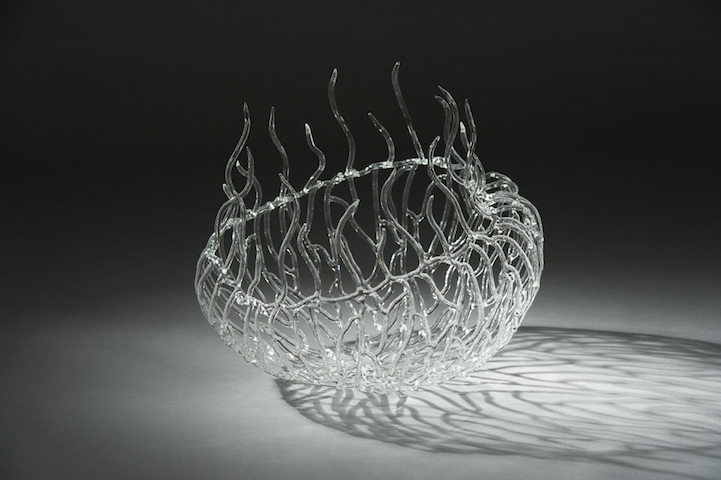

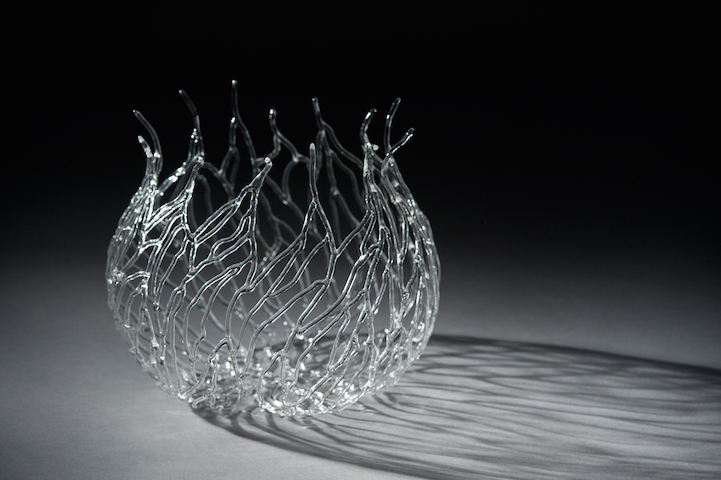

Using fire to manipulate thin rods of glass, artist Emily Williams creates delicate sculptures of organic life forms like coral, seaweed, and jellyfish. Fragile fronds, veins, and tentacles appear to ripple when cast under light, as if each plant and creature were made of the very ocean they were inspired by. Looking at the artist's work, it's amazing to think of the meticulous effort that went into shaping rigid rods into incredibly complex webs of glass.

From an early age, Williams has been fascinated by art, science, and natural history, thanks in part to the influence of her family. These passions morphed into a long career as an artist engaged in shaping physical forms using a variety of media like cast metal, cast glass, welding, and more. As her ideas and craft evolved, Williams fell in love with flameworking glass using a hand torch, which allows her to work through her concepts quickly. Her current glass sculptures of complex sea life forms are influenced by 19th century scientific illustration and scientific glass models.

We were able to ask Williams a few questions about her inspiration and creative process. Be sure to read that exclusive interview below.

Above: Glass Seaweed, 2014, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 20″ x 20″ x 20″

Glass Seaweed detail

How do your passions for art, science, and nature feed into each other?

As a child growing up, art, science, and nature were completely commingled. From as early as I can remember, I watched my father paint, sculpt, and design. But he was also a doctor, so I was constantly exposed to medical science. A lot of the old medical textbooks fascinated me, especially pictures of rare or advanced stages of disease. Medical instruments were often left on the kitchen table. It was a strange and wonderful childhood! My maternal grandparents were conservationists and loved the outdoors. We often went to hike and stay with them at their mountain property in West Virginia. I learned a lot about the natural world and the animal kingdom from my grandmother. On our outings, she often collected all sorts of road kill for the Smithsonian, where she was a docent.

I was wired early on to make the connections between visual art, science, and the natural world. For many years, I worked primarily in the figure. I was fascinated by anatomy and the human nervous system. Three years ago, when I started flameworking glass, I began with a sculpture called Spun Head. I had been working on a series of really large head drawings for several years prior to that. I created the head using thin 3 mm strands of glass. I was compelled to create a 3-dimensional glass drawing of a head. I layered the line in webs slowly from the center outward. The sculpture epitomizes my mental and physical transition into flameworked glass!

Nest, 2013, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 15″ x 20″ x 20″

Coral Skeleton, 2013, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 20″ x 22″ x 10″

What is it about glass that draws you to the material?

What initially drove me to work in flameworked glass was to gain a direct sense of immediacy in my creative process. I wanted the ability to spontaneously build sculptural form in glass using the hand torch. Since I had already worked with metal hand torches for decades, I had ideas about what was possible. I love the luminous glow that is emitted from the glass. When I layer up a lot of clear glass line into a sculptural form, the piece seems to generate its own light source. Combine this with the constant use of the torch flame and you have a very hypnotic process.

I remember reading an article back a while ago in the Glass Art Society Digest. In this delightful article, the woman writer referred to glass as a “metaphor slut.” I thought that was the funniest article I have ever read about glass as material. Glass is very metaphorical to me because of its inherent, fragile qualities. But isn't that the same quality that draws people to it? It is a sort of fatal attraction. Building different reef life forms such as coral out of glass has never made more sense to me than in this day and age. Many coral reefs globally are in great decline. This is a trend that could lead to a massive extinction of coral reefs in the next 25 years. I think a lot of people understand the metaphorical qualities of glass instantly when they view my work.

Jellyfish, 2013, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 15″ x 14″ x 14″

Jellyfish detail

What inspired you to choose subject matter like seaweed, coral, and jellyfish?

In these ocean life forms, I was interested in creating different patterns and movement. With the jellyfish and the seaweed sculptures, I wanted to capture the sensation of water as an invisible force. The jellyfish seems to glide off in a particular direction. In the seaweed sculpture, I moved into a wholly dimensional form where each branch arises from the base of the sculpture. The seaweed fronds appear to rise and sway in multiple directions.

With the hand torch and borosilicate rod, I am able build my work in stages. This allows me to add very fine details. For example, I am currently working on a very large brain coral. A photograph of an open brain coral inspired this sculpture. The photograph showed a brain coral fully opened and feeding. It almost looked like a clump of swaying spaghetti in the ocean! Ever since, I have been focused on different varieties of coral.

Glass Petal, 2013, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 15″ x 12″ x 4″

Glass Petal detail

The way you make these glass sculptures through flameworking is so unique. Can you walk us through your process?

I look at a lot of photography by divers and coral farmers. Photography is my jumping off point. Usually I am awestruck by a particular type of form such as the elegant curling of the magical feather star. The more I learned about the feather star, the more obsessed I became. It's a creature that looks like seaweed. It has feet so it can walk or climb on other sea creatures like fan coral. It can also swim by flapping its branches through the water. For me, this is a crazy kind of Dr. Seuss world. It gets even better when you see the utter madness of color variation in the feather star species.

When I begin a sculpture, there is always some sort of new problem to solve. With the feather star, the form itself required a new type of torch. I needed something small with a very long tip. This torch has a long custom tip that enables me to reach down inside the form for fusing the glass joints. For the feather star, I worked from one particular photograph; however, I also collected a lot of material about this creature. One of my problems was that in many photographs it is impossible sometimes to really understand the exact physiology. So I began culling online resources of rare books for historical scientific illustrations of feather stars.

My sculptural process has always involved a lot of drawing. I keep a lot of sketches, notations, and, lately, color studies for newer works. These drawings are my connection to what will be created. I determine the size of the sculpture. I figure out the different diameters of glass rod that I will be using. I also devise a test sample where I build out a very small fragment of the structure. I then run the glass test through a glass kiln annealing cycle. In the end, you can never plan or visualize exactly what will be created. This is the greatest reward of all. I am always relieved when I see that something will work. This is usually after I start building out the structures and patterns of the glass sculpture.

With the feather star sculpture, I made a series of drawings exploring the curling movement of the branches. I also hung a photograph of a particular feather star on the wall behind my glass bench. I then proceeded to develop each arm of the feather star curling in full length toward the center. These initial glass lines of the sculpture can take several days to finish. The bare bones of the sculpture determine the movement, the scale, and the stability of the piece. I carefully moved the torch slowly up the length of each glass line, bending it towards the center. As I did this, I also added temporary glass bracing to support these elements. In the end, the glass bracing was removed. Once the basic linear structure was finished, I then began the hugely fun task of building out the fine details of curving glass tendrils. This flameworking process can take several months to complete!

Water Burst, 2013, Flameworked borosilicate glass, 12″ x 10″ x 10″

Water Burst detail

Looking forward to your future creative work, what are you most excited about?

In the past six months, I have been working on feather stars and brain coral. Learning about these reef creatures has taken my work into a new direction. For three years, I have made large sculptures using clear borosilicate glass. During this time, I have stockpiled and experimented with all sorts of colored glass. But I did not have a vision or drive to use color until I started really learning about the different varieties of coral. For many months, I have been preparing for several pieces in color. I have been working on small blown elements and testing out different palette colors. I have also had to research and acquire some new, special torches that will accommodate the special needs of working borosilicate glass color. I think a lot of people believe glass artists can just pull out a different color and there you have it. There is a lot of chemistry in using borosilicate color. Each glass boro color is different and requires a special approach in the torch flame. It is a huge challenge, but the color visions I have are worth it!

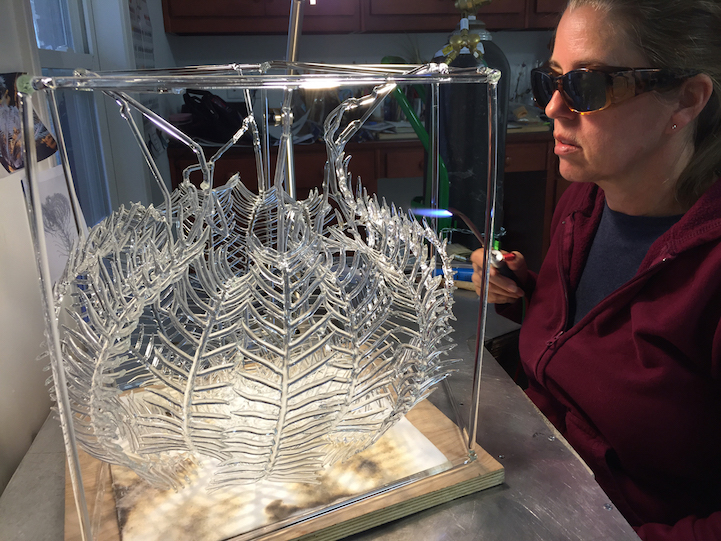

Sneak peek: Emily Williams working on new piece Feather Star, 2015

Emily Williams: Website | Videos | Facebook

Thanks so much for the interview, Emily!