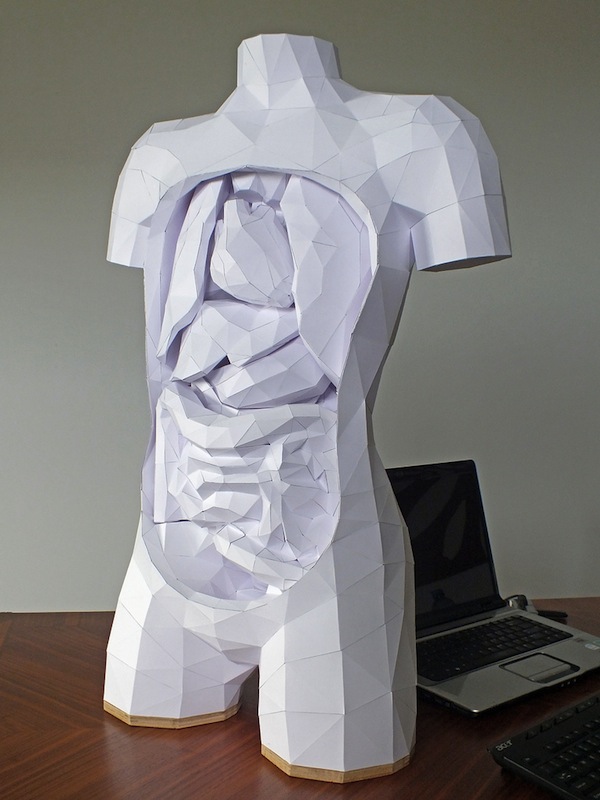

Four days ago, we first posted on Horst Kiechle's paper torso with removable organs and soon after we got to stand back in awe and watch as Kiechle's creative work zipped through the web, hitting the blogosphere with force. Not only did Colossal pick it up (one of our favorite, fellow art and design sites), so did BoingBoing, DesignBoom, Complex, Juxtapoz and NotCot, just to name a few.

Many of you were just as impressed as we were by this anatomically correct paper sculpture. In fact, we're sure many of you want to find out how exactly he created it. That's why we got in touch with the artist behind it to find out more. First, however, here's Kiechle, in his own words, on the feedback he's been getting on the web.

“Response to your post has been huge – now everyone wants one – or the patterns to build one,” Kiechle tells us. “Might have to put my current project on hold and work on simple versions of the torso for people to do themselves. This was part of the original idea, but got shelved when I moved from Fiji to Bangkok.”

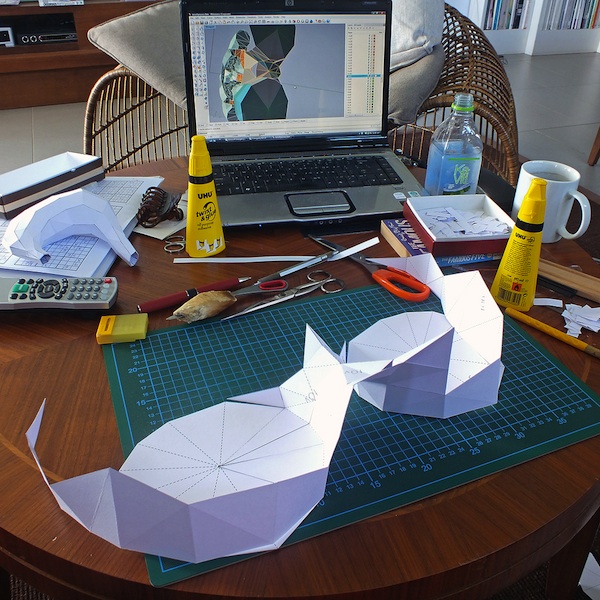

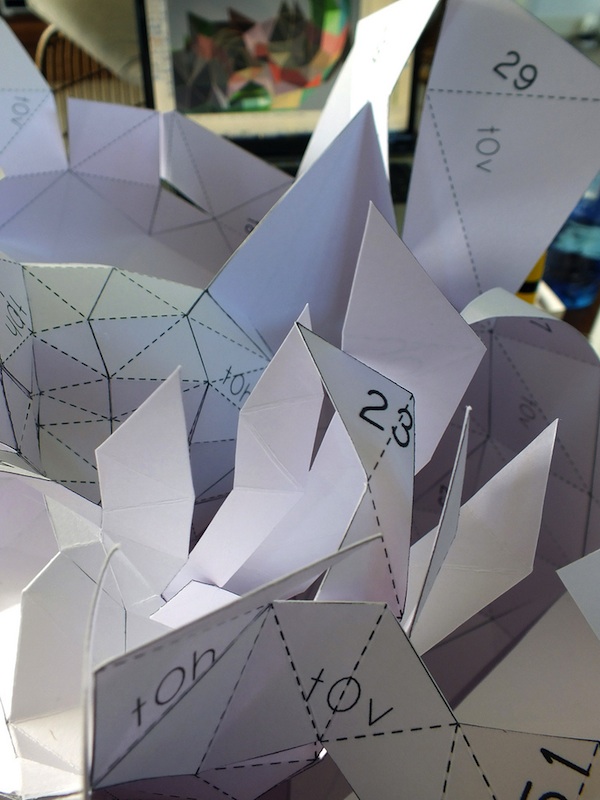

See below for some more “making of” shots, he's jut released, as well as an exclusive interview we conducted with the artist.

What was the creative process like in the paper torso? Which software program did you start with?

Unfortunately, I did not have access to one of those medical models, so I had to do everything from scratch. I started with searching the Internet for images of internal organs, but even with dozens of images of the pancreas I had no idea where to put them. A real breakthrough happened when I found on Google the Zygote Body website. Thanks to the different transparency levels, I could work out the relative positions of the organs. It is quite good for looking at the organs, as well.

The first torso I designed was with high-end immersive reality software during a residency at the CSIRO in Australia in 1997. Since then, I have trained myself to design straight in 3D software and, thanks to improved computer power and graphics, any 3D software will do these days, especially as one of the aims is to keep the polygon count very low so you can build the object manually. The skill comes with positioning the triangles in such a way that they suggest curvature with as few triangles as possible. For unfolding the 3D design into the 2D cutting and folding patterns, I have developed my own software over the past 15 years. Commercial software that does this sort of thing is now available, at Pepakura Designer for example.

How difficult was it to make?

The idea for this project came from Ms. Joanne Nakora from the International School Nadi in the Fiji Islands. Now, Fijians are famous for playing rugby, not so much for delicate paper craft. In order for the torso to survive in this environment, it had to be strong. Definitely strong enough for the organs to withstand the occasional kick across the class room.

Each design, therefore, consists of horizontal and vertical strips and, after laminating three layers together, it becomes quite strong. Additional strength should come from a layer of polyurethane after the teachers and students complete painting the organs.

Sometimes, the process of which strip goes where is a bit tricky. Not really difficult, just very time consuming.

Is this torso made only out of white card?

With the exception of the plywood base, which ensures the torso doesn't blow over in the wind, just white card 240g/m, and glue.

What did you find to be the most challenging aspect of this project?

The most difficult bit at the design stage was to make sure that the gap between the organs is large enough to slide them in and out. Also, it was challenging to create ledges the organs could rest on when the torso is in its standing position. The heart still has a tendency to fall out if the torso gets knocked. Something to improve upon in future versions.