Photographer Frédéric Lagrange began a love affair with Mongolia as a child, long before he ever had the chance to visit. Spellbound by his grandfather’s stories of being rescued by Mongol soldiers during World War II, Lagrange’s journey to this distant land collided with his professional journey into photography.

Seventeen years and innumerable trips later, Lagrange is finally ready to show his life's work to the world. In between editorial and commercial photo shoots for publications like Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, Louis Vuitton, and GQ, he packed his bags and invested his own time and money to pursue this passion project. After almost two decades of photography, he’s shifted his vast archives to create Mongolia, a publication that is a true work of art. The large format photography book captures the spirit of the Central Asian country, one that was largely unexplored by outsiders when Lagrange first visited in 2001.

Across 185 photographs, the story of Mongolia unfolds, as we travel with Lagrange during his 13-month-long trips. We see faces that transform from strangers to friends and the desolate landscapes that change with the seasons. Lovingly crafted with the care of someone who dedicated his life to documenting a country, the book is an incredible tour de force.

To fund the book, Lagrange turned to Kickstarter, where Mongolia has seen incredible success. Fully funded after just five days, the book has now doubled its original goal—an incredible feat for an art book that costs $200.

We were fortunate to speak with Lagrange about Mongolia and how his project has evolved over 17 years, as well as how he approached creating the book and his thoughts on his Kickstarter success. Read on for our exclusive interview and check out Mongolia, which is available via Kickstarter through October 26, 2018.

You became interested in photography while working as a model. What was it about photography that grabbed your attention and pushed you to pursue it as a career?

In my mid-twenties, I modeled for only a short three years but I had the chance to work with some amazing photographers who allowed me to have an insight into the photography world and were a great early influence. Being able to see that one could make a living and be creative as a photographer was a huge appeal.

I had the chance to spend time off the set with some of these photographers—like Mario Testino—and observed first-hand how they proceeded in life and work, their incredible amount of curiosity, constantly looking for new ideas, interested in people and so inspired by seemingly unnoticeable facts that they would, later on, turn into great photographic subjects. I was also studying international law and economy at the time, with the idea to work for the United Nations, but I had lost my inspiration, motivation, and interest in that field.

Everything I could aspire to be was within photography: to be creative, to travel, to be my own boss, to be independent, and ultimately to make a living all thanks to that amazing craft. All of those elements, combined with the early exposure into that world through modeling, made photography what I wanted to pursue with a fierce motivation and energy. At the time, I knew nothing about it, and I had never held a professional camera in my hand—I had to learn absolutely everything from scratch. At that point, I decided to move to NYC full-time and looked to work as a photo assistant. I started as a third assistant, then little by little learned more about the craft and technique and got to know more people in the industry. I assisted for three years and then in 2000/2001, I started to shoot. By 2002, I was busy shooting magazine assignments full-time.

Can you tell us a bit about what inspired your travels to Mongolia?

When I was a child, around 7 or 8 years old, my grandfather used to tell me stories of his days as a war prisoner in a German camp during World War II. He told me how he had been saved by a battalion of Mongol soldiers who were part of the Soviet army fighting along the allies. Those Mongol soldiers happened to be in the area where my grandfather was imprisoned.

They attacked the camp, chased the Germans and saved all the prisoners. He used to tell me how all these prisoners—US, British and French—embraced each other and celebrated together. I remember his laughter and teary eyes as he was telling me that story. As a child, I could feel that the event had been an important one in his life. They had saved his life and, ultimately, mine. Since then, Mongolia had a special place in my mind, even though as a child I did not exactly know where the country was.

What stood out to you about Mongolia that made you want to come back again and again?

I took my first trip to Mongolia in late August 2001. There was not much happening there back then and the country was not as popular or as documented as it is today. Just 11 years after the Berlin Wall had been torn down and all of the Soviet block had exploded, Mongolia was slowly waking up from those soporific decades spent under Soviet command and was slowly discovering democracy and capitalism.

There was a lot of confusion and chaos in the capital city, especially in the government, and the way the country was being run and lead. I remember being very intrigued by the desolation some parts of the capital city displayed. The typical Soviet-era architecture of the buildings was a particular visual fascination in its inhuman concealment. All of that, as a Westerner, was a complete novelty. I could see and understand how a political regime could affect people’s everyday life and psyche. That was fascinating.

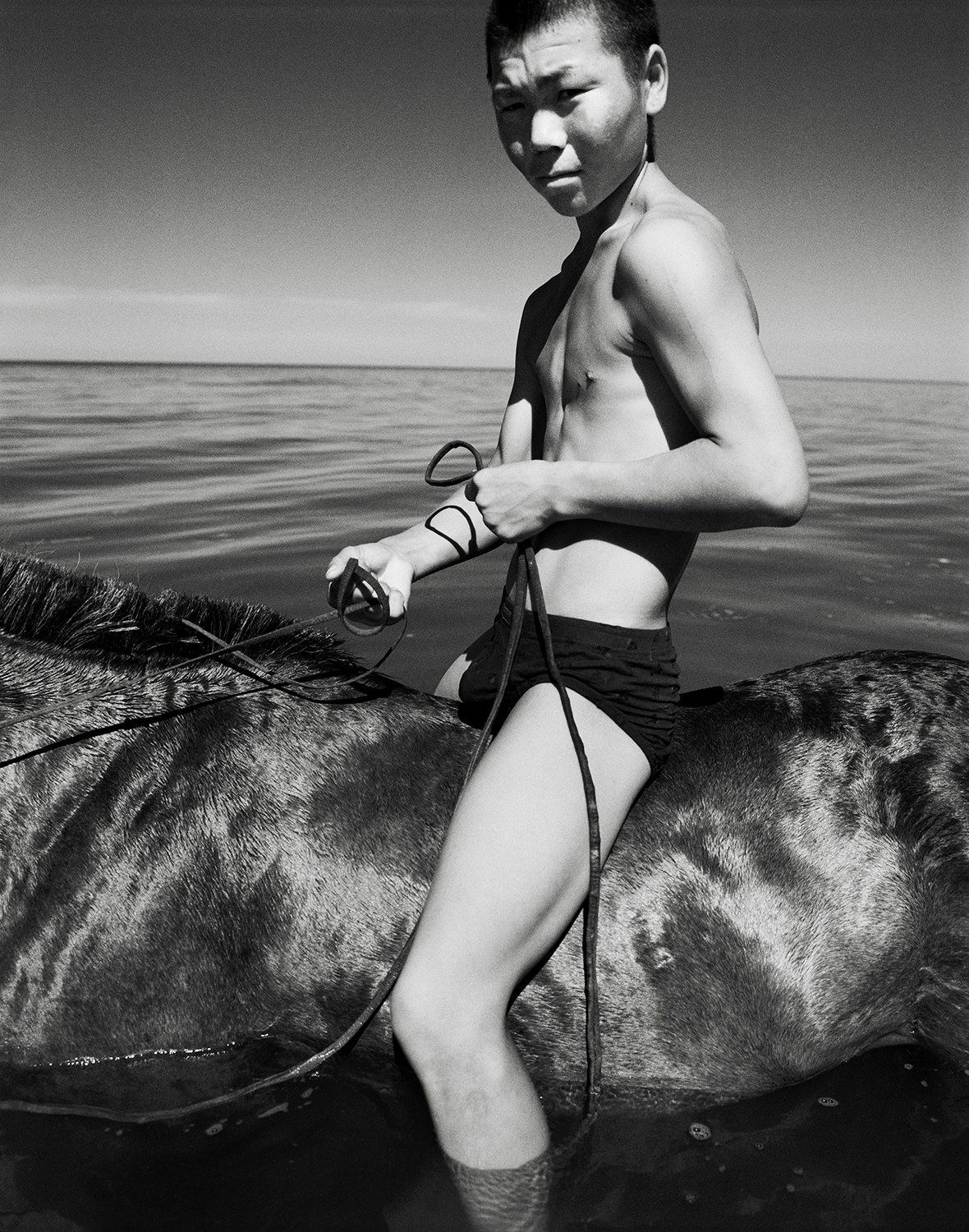

Then the drastic contrast once I drove only a few kilometers out of the city, where it was a natural glory. The Mongol countryside was the opposite of the whole linear organization of space and geometry that the Soviets had tried to inflict in the cities. Nothing was to be found there, and that was such a relief from the oppression of the cities. Once in the immense expanse of the countryside, I could see for miles and miles, in all directions. All around me it looked like a Rothko painting with three layers: the grassy ground, the remote mountain lines and finally the blue layer of the sky. All those elements made Mongolia a truly unique place I had never seen or experienced anywhere else in the world. And it is a massive country as well (five times the size of the UK) with so much to see and cover. I remember being very excited about the perspective of traveling throughout and seeing the entire country little by little.

When did you realize that this would become more than a single photo essay and a lifelong project?

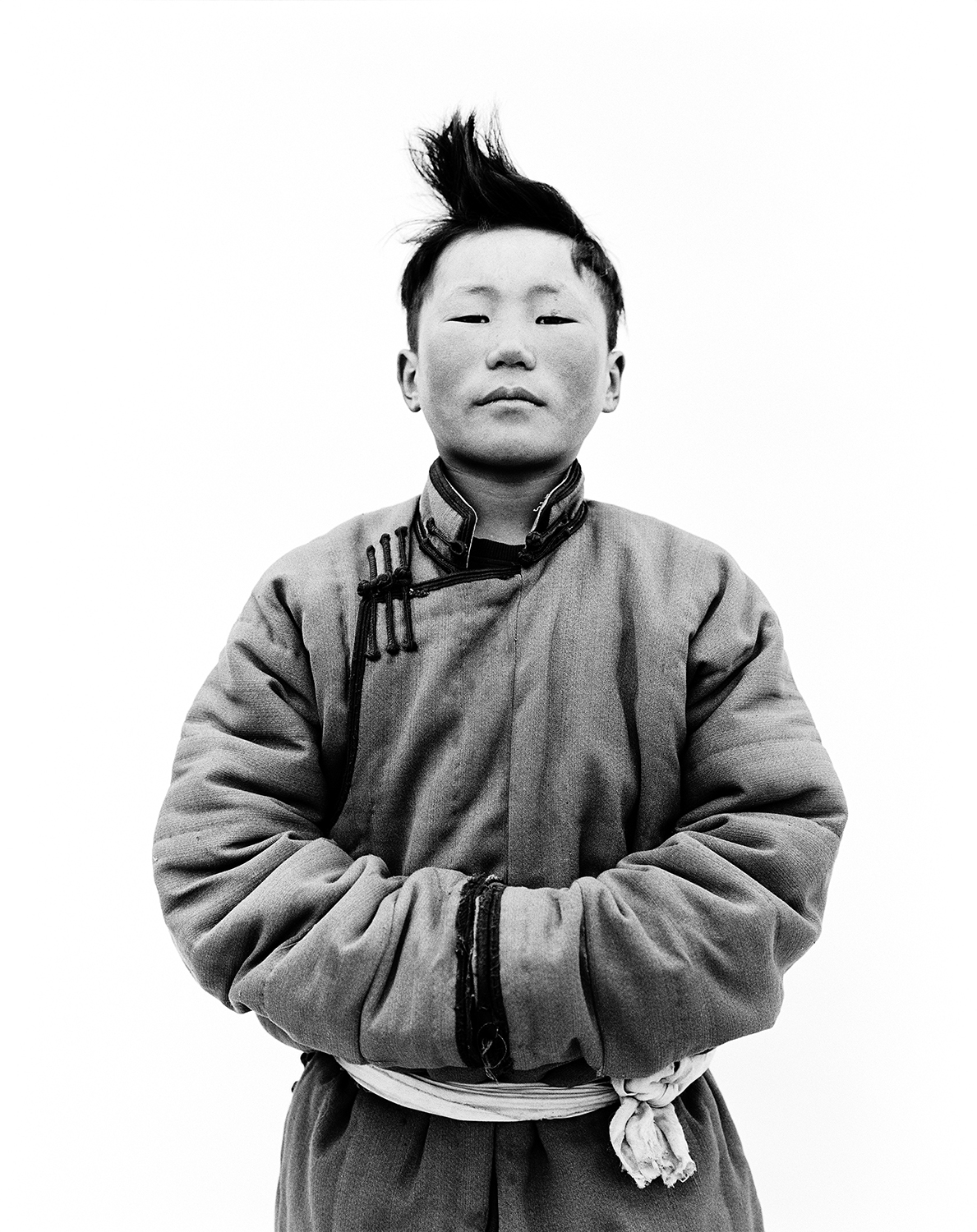

The first trip I made was more of a “scouting trip” I would say. I had the excuse of taking photos while traveling which made my time and expenses worth it in my eyes. Once there, though, I quickly started to shoot more than I had expected. Everything and everyone I saw and met were fascinating subjects. I had a bolt of black fabric with me that I would set up in the traditional ger (Mongol nomadic tent) and with the soft diffused light, the setting was perfect to shoot portraits.

On that first trip, I did a series of portraits of locals I met on my way with some other landscapes. To date, some of those images are still some of my favorites that I have shot in Mongolia. Once back in NYC, I processed all my rolls of film and showed the results to a few friends and art directors in the industry. To my surprise, a few magazines decided to run a story with the images and others encouraged me to pursue that body of work as a long-term project on Mongolia.

It was only during my second trip in the winter of 2002 though, that I truly realized the potential there was in this country, and the huge contrast there was between winters and summers and the change of landscapes, along with the difficulties to shooting in the extreme cold. All of those challenges made this potential project even more interesting and attractive. I decided then, I would work on a book. I had a 6-year plan then to complete it, but there was always another place to see, a season to cover, or some portraits to shoot at a particular time of the year. It turned out to be 16 years later that I would feel I had truly done due diligence and covered pretty much everything I had had in mind to see and photograph all those years.

How has your relationship to the country changed the more that you’ve traveled there?

I have learned to know the country and people quite well over the years—the psychology of the people, the way to approach them, their philosophy, their approach to life, what to do, not to do. I have learned a lot from being around those nomadic people from Central Asia. I feel I have a very good grasp of the country and overall I feel extremely comfortable in it and among the local people. They have adopted me as one of them. I was even given a Mongol name, “Гурван Зуу” or Gurvan Zuu.

During one of my earliest trip in Mongolia, one of my Mongol friends told me: “When Mongols travel, they know when they leave, they never know when they arrive.” That was everything I needed to learn. That sentence gave me the true sense of living in the moment, with the flow and flexibility. The more I planned and organized each trip I took with the limited amount of time I had, it never once worked out. Plans always had an unexpected turn, most of the time because of the extreme weather conditions.

(continued) And with time, I learned to break my rigid Western linear expectations and relaxed my grip, let go, and accepted the flow of the events without wanting and having much control or expectations. And things always turned out better than I could have planned them to be, allowing me to be in places in perfect timing and synchronicity to shoot some powerful moments. That really gave me a lot of confidence and trust overall for the unexpected and the unknown which can otherwise trigger apprehension and fear, a notion that I have since come to live by in my everyday life today.

That is the gift from this country, and possibly the biggest impact of my travels in Mongolia. But most importantly, I have made friends, people who have been incredibly supportive over the years, random strangers who have offered me their hospitality. I learned a lot traveling and working in Mongolia.

How have you seen Mongolia evolve over the course of 17 years?

The capital city, Ulaanbaatar, has incredibly evolved to catch up with some of the most vibrant cities in the rest of Central Asia. That evolution has been impressive to see. The riches, the technology, the level of sophistication that people have been able to learn and catch up with in such little time is astounding.

For instance, the first years I went there, it was very difficult and expensive to find chicken, eggs, fruits, and vegetables. As most of the year, it is too cold to grow greeneries or raise poultry, everything was being imported from China and Russia. Today, the supermarkets in the capital and most of the larger cities around the country are stocked with any products you are looking for.

What has your relationship been like with the Mongolian people themselves?

In the early years especially, people had a lot of questions as to what I was doing traveling all alone, in their country, so far from mine. They were intrigued, very curious. Then I visited those people again on subsequent trips and my relationship with some of them became friendly.

Mongols are very hospitable by nature, as the country is so vast and isolated, people have to take care of each other in order to survive in the countryside, especially during winter. Their behavior and hospitality are not limited to Mongols only, but also to anyone they cross paths with, including foreigners.

It’s safe to say that you’ve made lots of friends in Mongolia over the years. What’s been their reaction to the book?

They are all very proud of their country and to be Mongols, so to see a book of this scale coming out, about Mongolia, they are very happy. I have received many emails from Mongol people all around the world expressing their interest in my book project and relationship with their country and thanking me for the work I have done. It has been very positive feedback.

Is there a particular human experience you’ve shared with a local that you’d like to tell us?

I think most of the intense moments I have lived through in Mongolia were with my friend and guide Enkhdul. I met Enkhdul a few years back, in 2005, and since then he has been with me on all my big trips. We’ve been through some pretty intense moments together. One particular moment was on a frozen lake in northern Mongolia—Khovsgol Lake.

During winter, this lake has a 6-foot layer of ice, strong enough to bear the weight of a car or truck. We were driving on the lake in February 2005, following a trailer truck in front of us when all of a sudden, the truck collapsed into the layer of ice, and half disappeared. All of us in the car shouted with horror at the same time, the driver stopped the car at a safe distance and we jumped out of the car and walked slowly and cautiously to a few hundred feet from the truck.

The three occupants of the truck had jumped out and run away. There was a lot of unease between us, and the ice was cracking with a thunderous noise. Even our local driver, used to going that route in the winter, was unsure of the quality of the ice, but somehow still kept his cool, even though I could feel he was very anxious. After attending to the passengers of the truck, we decided to head back to the safety of the shore.

(continued) In our hurry to drive as fast as we could, one tire exploded as we were crossing a bridge of ice and we became stuck there. It took us half an hour to fix that flat tire, during which we all felt very anxious with the ever-growing loud sounds of the cracking ice all around. It was a truly frightening moment. We finally reached the shore, all relieved and safe but not without having had some cold sweats. That was one of the many experiences we shared while traveling together over the years.

One time, Enkhdul told me that he lived and experienced this kind of event in his own country only with me and that his wife was always a little worried when she knew the two of us were traveling together.

I know it’s hard to rank your images because I’m sure they all have special meaning but are there any standouts for you that hold personal significance?

I like the Two Men on Ice picture I shot that day on the frozen lake during the event I described above. I also like some of the portraits I shot against white and black backgrounds. Those are very straight-forward portraits, but the process of shooting portraits of people who had never had a camera pointed at them was very interesting and very raw. There was no pretense and that made the whole process very unique.