O'Keeffe's Life, Continued

The 1920s

In late 1916, O’Keeffe sent a selection of her abstract drawings to a friend in New York City who then showed them to Stieglitz. The two struck up a friendship and later a romantic relationship—it was Stieglitz who offered O’Keeffe her first solo show at his gallery, Gallery 291. By 1918, she had stopped teaching (this time in Texas) and moved to New York. Stieglitz had promised her a year of being free to paint.

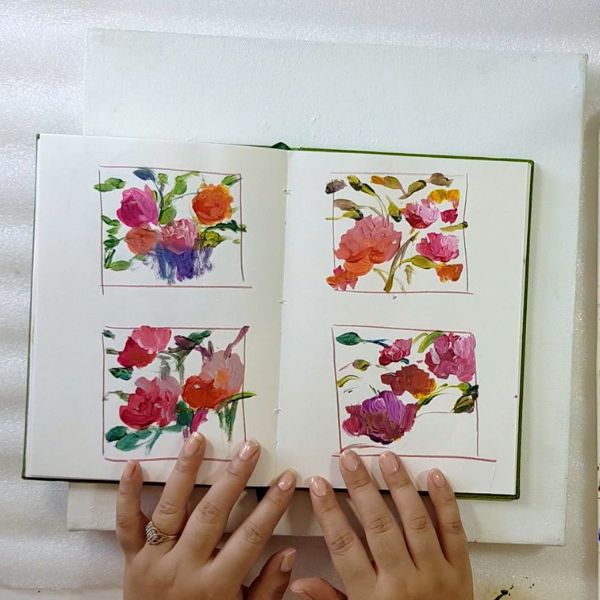

Within several years, O’Keeffe had gained a reputation for her New York City skyscrapers—undoubtedly inspired by her tenure in Manhattan—and abstracted flowers painted during her summers spent with Stieglitz in Lake George, New York.

At the end of the 1920s, O’Keeffe was feeling stifled by the sameness of the landscapes. “Here at Lake George everything is very green,” she wrote in a letter to a friend. “I look around and wonder what one might paint!”

View this post on Instagram

Discovering New Mexico

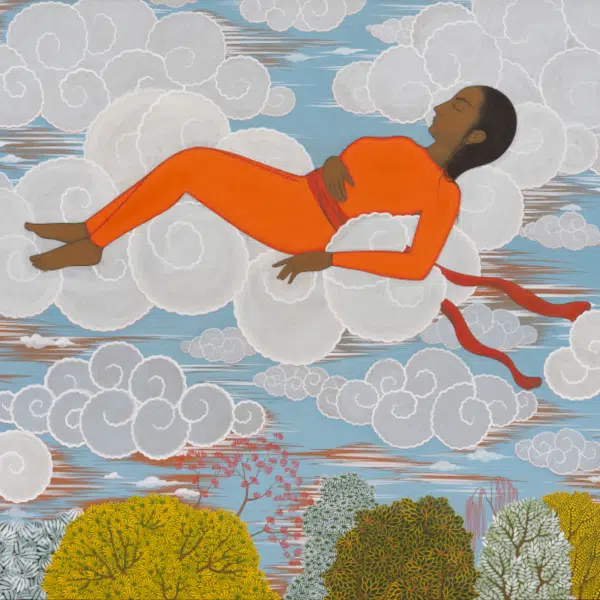

The summer of 1929 marked the first of many of O’Keeffe’s trips to northern New Mexico. She spent the season there and felt as though she had found her “spiritual home.” In another letter, she spoke of the ease in which she felt being there. “You know, I never feel at home in the East like I do out here. I feel like myself and I like it.”

View this post on Instagram

For the next 20 years, O’Keeffe lived part-time in New Mexico and made the permanent move in 1949 (three years after Stieglitz's death). She painted the landscape as well as pictures of distinctly Western imagery such as animal skulls. Although elements like these were recognizable, they were each punctuated with the abstraction for which O’Keeffe was so well known.

In addition to living in the Southwest, O'Keeffe traveled internationally in the 1950s and created paintings based on the places she visited, such as Mount Fuji in Japan. By the 1970s she was suffering from macular degeneration and completed her last unassisted painting in 1972. She continued to create work with the help of several assistants. “I can see what I want to paint,” she said at the age of 90. “The thing that makes you want to create is still there.”

O'Keeffe died on March 6, 1986, at the age of 98.

Photography's Influence and Controversy in O’Keeffe’s Work

Because of her relationship with Stieglitz, modern photography played a pivotal role in O’Keeffe’s work. The pictures of Paul Strand, for instance, inspired her to crop the subjects in compositions. The results were images that were detailed (in terms of color and texture) yet abstract. A work of flower art, for instance, would be enlarged across the canvas so that only part of it was visible. Although recognizable, its trailing forms would double as bold stylizations of a plant.

View this post on Instagram

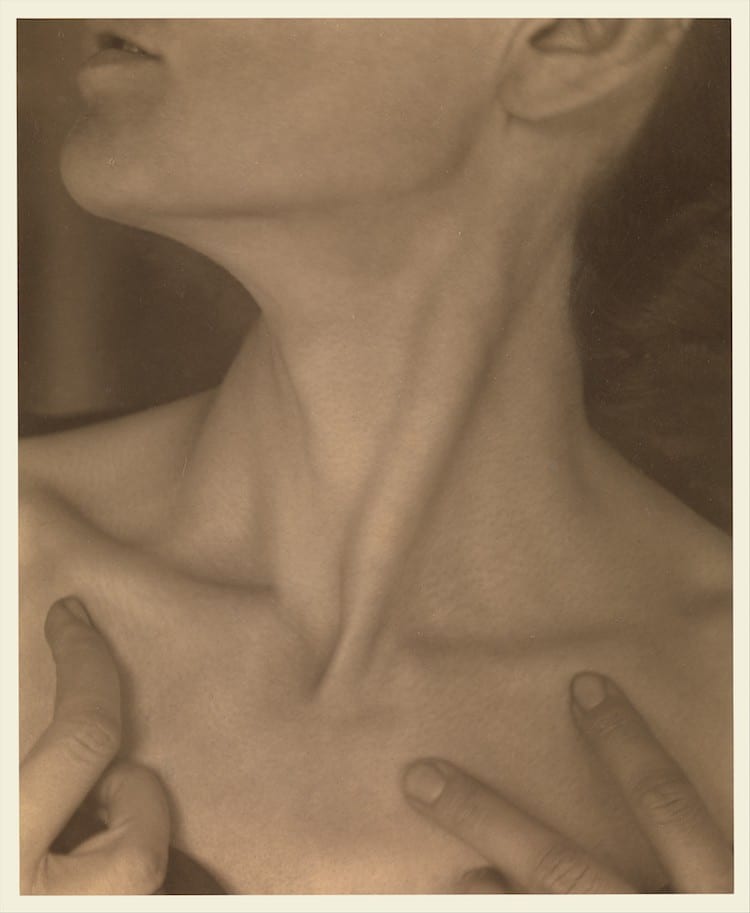

The way in which O'Keeffe zoomed-in on a subject and focused on abstraction through color caused controversy in how she viewed her art versus the critics that reviewed her paintings. When she and Stieglitz spent the summers at Lake George, he created a series of more than 300 photographs of O'Keeffe. At his 1921 retrospective, Stieglitz showed 45 portraits of his wife—including many nudes. These images, along with what her husband said and wrote about her paintings, conveyed the idea of O'Keeffe as a “sensual and sexual creature.”

Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O'Keeffe – Neck. 1921. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Two years later, at a show of more than 100 of her paintings, critics were colored by what they had heard years prior. They viewed O'Keeffe's pictures as expressions of her sexuality—something she did not intend to evoke at all. O'Keeffe was “shocked and disheartened” by critics' reviews, and it shifted the focus of her work. She withdrew from such heavy abstraction and instead turned her attention to recognizable forms that weren't open to interpretation. Unfortunately, even straightforward pictures of flowers—influenced again by photography—continued to be scrutinized as an expression of O'Keeffe's sexuality.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Visit O'Keeffe's Legacy at the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

View this post on Instagram

Located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum is the best way to experience her work and get insight into her creative process as well as the landscape that inspired her. It holds over 3,000 of her works, and the institution is also responsible for the preservation of her two homes and studios in northern New Mexico.

Related Articles:

Art History: The Evolution of Landscape Painting and How Contemporary Artists Keep It Alive

12 Famous Flower Paintings that Make the Canvas Bloom

Top 8 Oil Painting Techniques All Beginners and Professionals Should Know

11 Different Types of Painting That Every Artist Should Know