Louisa May Alcott photographed late in her life. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Most authors find themselves adding elements of their own personality and personal history to their characters—whether they do so consciously or not. Among the great semi-autobiographical characters of modern times is Jo March, the central protagonist of the enduring classic Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. Like Jo, Alcott was one of four close-knit sisters growing up in Concord, Massachusetts in the mid-19th century. The similarities do not stop there. In a masterfully crafted meta-narrative, young Jo writes her own story throughout the novel—blending the character with Alcott, at times beyond easy recognition.

In Little Women, Jo opines, “I want to do something splendid before I go into my castle—something heroic, or wonderful—that won’t be forgotten after I’m dead. I don’t know what, but I’m on the watch for it, and mean to astonish you all, some day. I think I shall write books, and get rich and famous; that would suit me, so that is my favorite dream.”

For Alcott, writing books was more than a dream; it was a means of survival and a source of pride. A female writer in the male-dominated publishing world of the 19th century, Alcott made her mark. The journey to acclaim, however, was not easy or sure.

An Unconventional Childhood

Orchard House, home to Louisa May Alcott from 1858 to 1877 and where she wrote “Little Women.” (Photo: Stock Photos from LEE SNIDER PHOTO IMAGES/Shutterstock)

Louisa May Alcott was born in 1832 in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia). In 1834, the family moved to Boston. Amos Bronson Alcott and his wife Abby May would eventually have four daughters, of which Louisa (like Jo) was the second eldest. Amos was a teacher and a Transcendentalist who associated with the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

In 1840, the family relocated to Concord, Massachusetts. The town—famous for its importance to the opening act of the American Revolution—became a center of the progressive literati. Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thoreau, and Emerson were all mid-century residents. Association with such writers, paired with the radical thinking of her parents, set young Louisa on a path towards literature.

The family moved frequently and often lacked funds. Louisa studied at home, learning from her father and (when could be afforded) governesses. Amos believed in a revolutionary approach to children's learning. Louisa once described her father's method as, saying it “unfolds what lies in the child’s nature as a flower blooms.” Despite his innovations and radical thinking, her father was often dependent on the aid of his wealthier friends and the supplemental income of his wife and children. Louisa and her eldest sister both worked as governesses once old enough to help support the family.

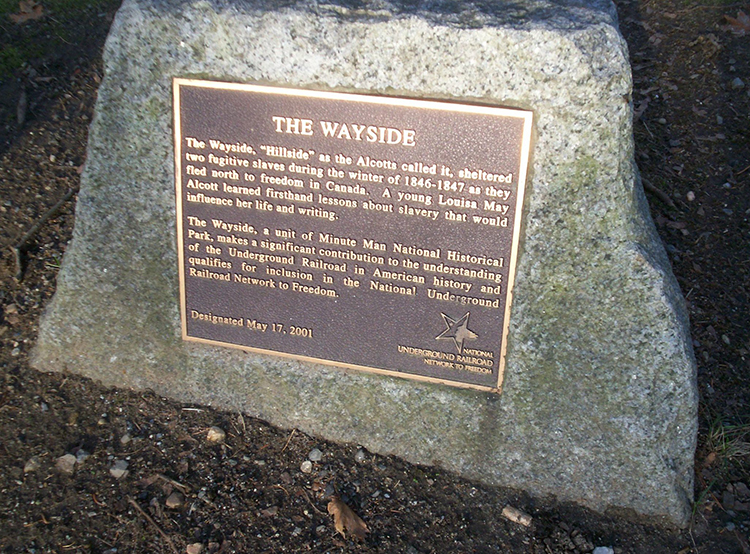

A marker to the Wayside's role as a stop on the underground railroad. The Wayside was the home the Alcott's sold to Hawthorne. (Photo: Midnightdreary via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Concord remained the family home even as its members roved around. For this reason, Little Women would eventually be set in the town. The family lived in a home known as Orchard House from 1858 to 1877—after selling a previous home to Hawthorne. The place became as eclectic as its residents. The youngest girl May was an artist, much like Amy in Little Women. Amos built his daughter a studio. Sadly Elizabeth, like the beloved Beth of the novel, passed away young before the family's arrival in the house. It was in the Orchard House that Louisa would write Little Women, as well as countless other written works.

Writing for a Living

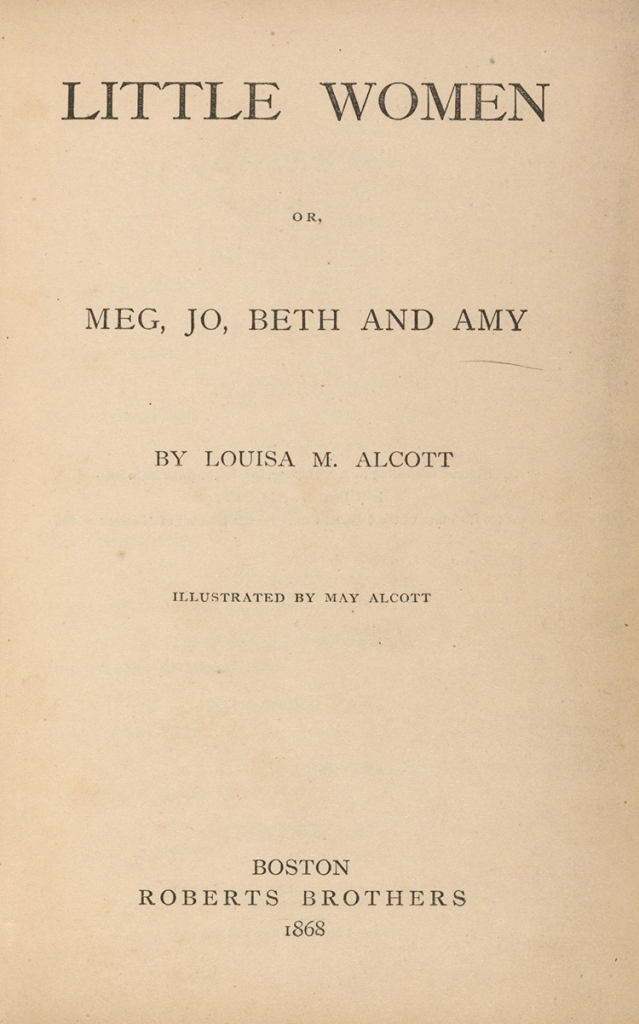

“Little Women” title page from the 1868 first edition. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Louisa May Alcott began writing at an early age, surrounded by the libraries of her father and the likes of Hawthorne. Her first known thriller story (based on a popular print genre) was written in 1848. She also wrote essays inspired by her personal experiences as a working woman.

Reportedly, a publisher told the young author, “Stick to your teaching, Miss Alcott. You can’t write.” Unfortunately, the family's financial situation necessitated any means of income possible. The 1850s were a difficult time, with young Louisa working in Boston while she continued to write. She was, like the March sisters, a great fan of the theater.

Alcott's poems and essays began, slowly, to appear in magazines. Her first book of short stories was published in 1854. Entitled Flower Fables, the stories had been written for a young Ellen Emerson (Ralph Waldo Emerson's daughter). The budding author received only $35 in share of the profits. She would go on to write many more stories for children, some of which would not be published till after her death. Her time in Boston was instructive, however. Coming from a family of abolitionists and feminists, she traveled in a reformist circle that included John Turner Sargent and William Lloyd Garrison.

In the early 1860s, during the Civil War, Alcott's career gained momentum. Alcott worked as a nurse in a Union Army hospital, during which she contracted typhoid. She wrote Hospital Sketches about her experience. The work was published serialized, then as a book in 1863. It followed a female character with humor and gained Alcott some literary acclaim. She spent the 1860s writing many gothic thrillers to bring in cash through sale to magazines. She also published under a man's name at times, A. M. Barnard.

Alcott's most significant work, Little Women, was also written during the decade of the war. Her publisher asked for a novel for young women—a burgeoning potential market. Little Women was published in 1868 as Little Women: or Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy, the first half of the book as it is sold today. The novel follows the four young March sisters who learn to work, learn, and love in Concord. The girl's mother is a reformer and social advocate, much like Alcott's. The father is an existential sort of man who spends most of the first novel away in the war.

Semi-autobiographical in nature, the novel and its sequel (following the sisters as they age, collectively known as Little Women today) were incredibly popular. The parallels to Alcott's life are distinct—including sibling rivalries and parental frustrations. Unlike Jo, Alcott never married. However, the author's love for her family and passionate support of such causes as abolition and women's rights come through clearly in her alter-ego.

The books were the financial answer her family needed. Alcott wrote, “Twenty years ago, I resolved to make the family independent if I could. At forty that is done. Debts all paid, even the outlawed ones, and we have enough to be comfortable. It has cost me my health, perhaps; but as I still live, there is more for me to do, I suppose.” Alcott went on to write two well-received sequels following the March family. She wrote countless stories, many targeted at children. Although she never had children, Alcott adopted a niece and nephew respectively upon the death of two of her sisters.

Alcott died at 55 in 1888, only two days after her beloved father. Today she is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord on “Author’s Ridge,” where she lies close to her childhood mentors Thoreau and Emerson. Her achievements stretched from being the first woman to register to vote in Concord to writing a novel that unequivocally stands beside the likes of Thoreau in the canon of great literature.

Literary Legacy

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts. (Photo:

Author Kenneth C. Zirkel via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little Women remains one of the most famous works written by a 19th-century female author—or perhaps any female author ever. The novel inspired stage and television adaptions—not to mention seven feature films. From the first silent adaptation in 1917 to Greta Gerwig's 2019 rendition, the story of the March sisters—and by extension the Alcotts—has proved its enduring appeal. History's most famous actresses have taken on the roles of the sisters—including Katharine Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, Winona Ryder, Kirsten Dunst, Emma Watson, and Saoirse Ronan.

Alcott herself had mixed feelings about her literary legacy and the primary role Little Women played in it. She expressed at times that she found the novel dull, full of the ordinary foibles of her sisters. However, the young women who read her novel found exactly the opposite: they saw their lives and concerns held up to them in a mirror that held both moralism and mirth.

Alcott did keep her literary integrity in one important aspect: she refused to marry Jo to Laurie, the beloved next door neighbor of the March sisters. “Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life…I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please any one,” Alcott wrote in her journal.

An RKO Radio Pictures lobby card for the 1933 “Little Women” film starring Katharine Hepburn as Jo. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

As Sophie Gilbert pointed out in The Atlantic in 2018, “the wealth of adaptations of Little Women over the past century is proof of its durability, and also its malleability.” For Gilbert, it is Alcott's “ambivalence” about a novel for girls which ends up putting so much of the author in the text. “Jo’s creativity, her nonconformism, and especially her anger—that energy constantly undercuts the sanctimony Alcott dreaded in a genre that she, without blood and thunder, found ways to sabotage in Little Women… she explored women’s place in the home and in the world—wrestling with the claims of realism and sentimentality, the appeal of tradition and reform, the pull of nostalgia and ambition.” It is perhaps for these reasons that readers and viewers keep returning to Alcott's novel.

Visiting Concord

Photo: Stock Photos from WANGKUN JIA/Shutterstock

Today, many aspiring authors and readers touched by Alcott's words make a pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts. For anyone interested in the literary canon of America, Concord hosts must-see sights. One can stroll the beautiful shores of Walden Pond where Thoreau observed and wrote poetically of such small natural moments of battles between ants. One can visit the charming main street with brick facades and pricey antique stores. The Sleepy Hollow Cemetery holds the graves of Alcott, Thoreau, and Emerson, among others. Concord is also historically important as the site of the Battle of Lexington and Concord at the start of the American Revolution.

Alcott's beloved home, Orchard House, has been preserved. It is open to the public as a museum dedicated to the author. It remains much as the family left it. Youth creative writing and theater workshops are held on the grounds—a development which one imagines would please the Alcott family. One can also visit The Wayside, the historic house once owned by the Alcotts and Nathanial Hawthorne that's now part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

Although 150 years may have passed since such luminaries walked the halls, visitors can still find themselves transported by the words and personal possessions the authors left behind.

The Old North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts. (Photo: Stock Photos from JAY YUAN/Shutterstock)

Related Articles:

18 of the Best Independent Bookstores to Visit Across the United States

Get To Know F. Scott Fitzgerald, the Legendary Author Responsible for ‘The Great Gatsby’

10 Facts About Jane Austen, the Beloved ‘Pride and Prejudice’ Author

5 Fascinating Facts About Margaret Wise Brown, the Adored Author of ‘Goodnight Moon’