Photo: Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

During the Renaissance, Michelangelo made a name for himself as a master of humanist sculpture. The Florentine artist's unrivaled ability to realistically represent the human form is evident across his entire body of work, with the famous David and Pietà at the forefront. Though undoubtedly among his most well-known works, these pieces are far from Michelangelo's only marble masterpieces—a point that is saliently proven by his Slaves.

Crafted in the early 16th century, this pair of sculptures were originally part of a papal commission. Ultimately left unfinished and omitted from the final design, the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave now serve as highlights of the famed Musée du Louvre, where they stand as symbols of Michelangelo's “quest for absolute truth in art.”

A Monumental Commission

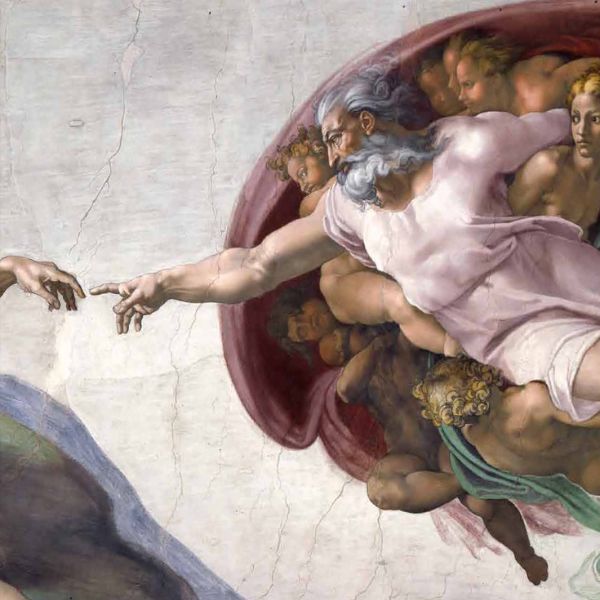

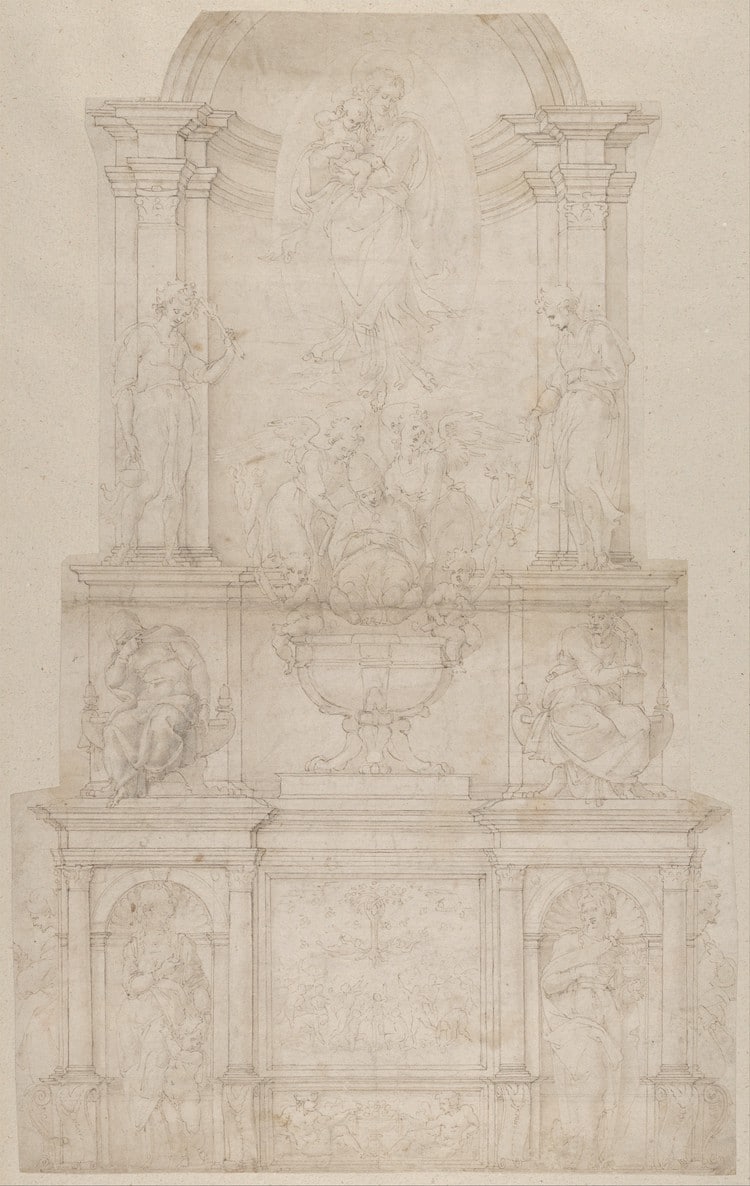

Michelangelo, “Design for the Tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere,” 1505-1506 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art [Public Domain])

According to written sources and surviving sketches, this freestanding tomb would tower at over 32 feet tall. Inside, it would house a chapel, while its three-tiered exterior would feature life-sized sculptures of saints, angels, prophets, and slaves. According to Michelangelo's biographer Giorgio Vasari, these unprecedented designs promised a monument that “in beauty and pride, richness of ornamentation, and abundance of statuary surpassed every ancient imperial tomb.”

Horace Vernet, “Julius II Ordering Bramante, Michelangelo, and Raphael to Build the Vatican and Saint Peter's,” 1827 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Even when Michelangelo completed the ceiling in 1512, the pope remained preoccupied with plans for the basilica. By the pope's death the following year, Michelangelo had only commenced carving three sculptures—a seated Moses and the two slaves—leaving the holy figure's heirs to rethink the pope's grand plans.

They presented Michelangelo with a second contract detailing a smaller, subdued version of the tomb. While they anticipated a seven-year timeline, completion of the tomb—whose design was again drastically altered in 1516, 1532, and 1542 and which now exists in Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome—would take forty years. “And so I find,” Michelangelo wrote in 1542, “I have lost all my youth tied to this tomb.”

To make matters worse, these ever-changing plans ended up omitting some of Michelangelo's nearly completed sculptures—including the Slaves.

Michelangelo's Slaves

(Left Photo: Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]; Right Photo: Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

In terms of their body language, the two figures have little in common. The Rebellious Slave features a “coarser figure whose whole body seems engaged in a violent struggle,” while the Dying Slave depicts a “superbly young and handsome, and apparently in a deep (perhaps eternal) sleep.” Both, however, exhibit markers of Michelangelo's signature skill: a lifelike approach to the human form.

This is evident in the figures' expressive faces and gestures, richly detailed anatomical features, and asymmetrical postures. Known as contrapposto or “counterpose,” this stance gave Michelangelo's figures a realistic look and feel while also evoking the Renaissance focus on balance, harmony, and the ideal form.

An Unfinished Legacy

Michelangelo, “Studies for the Sistine Ceiling and for the Tomb of Pope Julius II” (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Why did Strozzi move the marbles to France? After causing controversy by opposing the rule of Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Strozzi was exiled to Lyon—and so, in turn, were the Slaves. First, the pair were placed in niches in the courtyard of the Château d'Ecouen, a castle near Paris. Then, they found a home in Cardinal Richelieu's palace in Poitou. In 1749, the Duke of Richelieu brought them to Paris, and, after a noblewoman attempted to illicitly sell them in 1793, they were made French property and entered the Louvre's collection in 1794.

Photo: Stock Photos from Heracles Kritikos/Shutterstock

Today, the Slaves are among the museum's many sculptural treasures—a collection that includes gems like the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. As the Louvre's only Michelangelo marbles, they are arguably his most famous Slaves. They aren't, however, the only ones. In the 1520s and 1530s, Michelangelo sculpted four more Slaves, which are now located in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence. Like the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave, these figures were omitted from the final design, and remain incomplete—a fate that, fittingly, leaves them poignantly imprisoned within the stone.

“I saw the angel in the marble,” Michelangelo once remarked, “and carved until I set him free.”

Related Articles:

A Detailed Look at Bernini’s Most Dramatically Lifelike Marble Sculpture

18th-Century Sculpture Has a Delicate Net Carved Out of a Single Block of Marble

Exquisite 19th-Century Sculpture Cloaked in a “Translucent” Marble Veil

How Caryatids Have Beautifully Blended Sculpture and Architecture Since Ancient Times