Ohan Breiding, “Belly of a Glacier (To dress a wound from what shines from it) II,” 2025. Giclée prints. Site specific dimensions; 11 x 22 feet overall. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

With the world's rising temperatures, more glaciers than ever are melting rapidly. This has caused communities to mourn the loss of what was and to try to prevent further devastation. Swiss-American artist Ohan Breiding has captured the complexities of this situation with an experimental documentary and photography series that ruminate on the imminent loss of the Rhône Glacier.

Now on view at MASS MoCA, Ohan Breiding: Belly of a Glacier documents the efforts of residents to place thermal blankets on the ice, as a way of slowing the inevitable. Because, despite this recent attention, scientists predict that the Rhône Glacier will disappear by 2050. To that end, Breiding also visited the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility in Lakewood, Colorado, which preserves ancient ice cores like small time capsules.

“Ohan Breiding’s work is a powerful, intimate portrait of a dying glacier,” said Susan Cross, MASS MoCA Senior Curator. “The stunning photographs and video make the loss feel very personal—as it should, given that we are part of the ecosystem being forever transformed by climate change.”

Their work demonstrates how this ice represents something highly personal and why its disappearance feels like such a loss. Aside from the obvious ecological impact, this ancient ice is a bridge to the past, literally freezing history. Once it is gone, that past is somehow washed away. It's certainly personal for the artist, who was raised in a Swiss village not far from the Rhône Glacier and has fond memories of visiting the site with their family. These memories are incorporated into the film, which takes viewers into the melting core of the glacier.

Breiding hopes the installation will help people view “time as something fragile, how love and loss are deeply connected, that we’re a small part of something much larger.” As more communities mourn the loss of these glaciers, even holding funerals and creating memorials to them, Breiding's rumination on the matter is more urgently needed than ever.

Ohan Breiding: Belly of a Glacier is on view at MASS MoCA through December 14, 2025. We had the opportunity to speak with the artist about this moving project and what it means to them. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

Ohan Breiding, “Belly of a Glacier,” 2024. HD video, with audio, 32:55 min. Ed of 2 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

How did your childhood influence your decision to undertake this project?

The German etymology of the word “home” originates from “Heimat” meaning “home” or “haunting,” and “Gast,” meaning “guest” or “ghost,” so as part of my solo exhibition, Belly of a Glacier, I examine my own roots and childhood as a visitor and someone who has returned to their childhood home and to the remains of the glacier. The film, Belly of a Glacier, with the same title as the exhibition, begins with an analogue 35mm photograph that depicts my childhood self on a sled with my father standing by my side, wearing a red snow suit, blurry in movement. My mother took this photograph. I filmed this snapshot as a way to keep both her gaze as well as the landscape alive, freezing it in time.

My childhood best friend’s teenage daughter, Juna, narrates the beginning of the film in her native Swiss German tongue, the language indigenous to the Rhône Glacier. She acts as my alter ego, recalling an early childhood memory: “It is December. I walk out into the snow. With each step, I sink down a little. My body compresses the ground beneath me. Making a crunching sound. Everything is slick and blueish white. Large snowflakes fall down onto me. One lands in my palm. It is perfectly symmetrical, with six points radiating from the center like a flower. I watch it change shape. The heat from my body making it disappear.”

This statement implicates my body in the melting of the snowflake. As the story is told, the photograph slowly turns to red, signaling a fever as well as the aging of the analogue print—cyan and yellow dyes in color film degrade faster than the magenta dye over time. I’m interested in how analogue photography and film conjure up feelings of nostalgia, which animate my childhood memories of the Rhône Glacier.

Ohan Breiding, Belly of a Glacier, 2024. HD video, with sound, 32:55 min. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI Gallery, Los Angeles

What do you most enjoy about working with the natural world and landscape?

I love working outdoors in landscapes that are much older than me. I imagine the natural world as a place to witness time and learn through the spirit-mind (Geist), through intuitive insight. Glaciers are spiritual landscapes for me. They offer a space for slowing down, deep listening, embodied knowledge, and learning via the senses. The natural world is also inherently queer: shapes are varied, in flux, unique. Nothing is perfectly straight outdoors. Water transitions between gas, liquid, and solid states, much like the fluidity of trans-identities. Mountains move and grow. The glacier is both dead and alive, a haunting of sorts, and its body (ice) acts as a trans-national/trans-temporal matter that offers a new conception of time (beyond the linear) and place (beyond fixity). Also, this applies to the medium of photography/film, which grasps to restore what has been abolished by time, by distance, and to attest that what we see in the image did indeed exist.

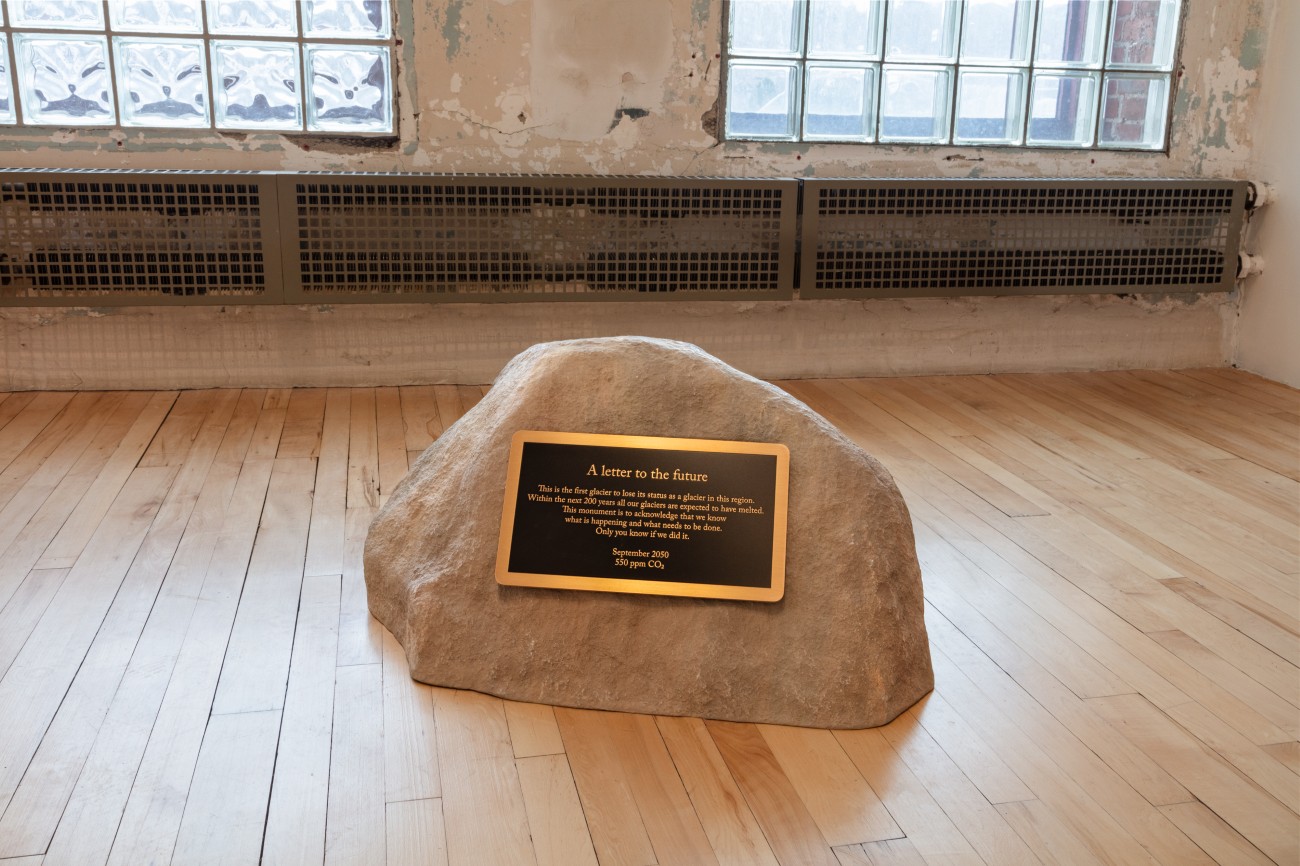

Ohan Breiding, “Even the stones are alive a letter to the future),” 2024. Bronze and fiberglass. 15 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 27 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI (Photo: Jon Verney)

These glaciers almost take on human qualities in the way the public mourns them. Why do you think that is, and how did that move you?

Cryologists—those who study ice—use corresponding language across the bodies of humans/animals and glaciers: “glacier tongue,” “glacier snout,” “belly of a glacier,” and “calving.” I am interested in this relation because it already unsettles a distanced process of scientific study by forming a kinship with animal life and in gesturing to embodiment as a form of study, which is what I did as I traveled to and across the glacier.

In order to understand what is happening to our climate and to our glaciers, we must foster attendance to what the ice has to say. In my exhibition, I consider concepts of fever, bodily fragility, and glacier calving—which is paralleled in the film by the birth of a cow, as well as the calving of a glacier (the death of a glacier). Glacier funerary practices began in 2019 when Iceland constructed the first memorial to mark the death of its Okjökull Glacier. Glacier funerals have since been held around the world to mark the melting of glacial bodies.

Death is for the living and when I staged a speculative funeral for the Rhône Glacier, I am asking the audience: What does it mean to mourn something before it has perished? How do we prepare for this imminent loss? Does mourning help us feel the urgency of this loss, as a problem of anthropomorphic climate destruction? Can acts of mourning mobilize us to protect the most vulnerable–those who will be most affected by global warming and sea levels rising?

Ohan Breiding, “Belly of a Glacier,” 2024. HD video, with audio, 32:55 min. Ed of 2 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

What was the most challenging part of bringing your vision to life?

The most challenging parts were also the most invigorating ones. I knew years ago that I wanted to film the birth of a cow, but planning this was quite challenging and involved a lot of planning with a farmer in the Swiss Alps who only communicates via a landline. Also, staging the glacier funeral in a studio in Los Angeles and working with animal trainers to film the last funeral attendant, who is an adult Hollywood cow named Bugs, was quite challenging but ultimately so rewarding.

Ohan Breiding, Belly of a Glacier, 2024. HD video, with sound, 32:55 min. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI Gallery, Los Angeles

Did anything unexpected happen in the creation of Belly of a Glacier?

During my initial research, I was surprised to learn that the villagers from Obergoms, who live below the Rhône Glacier, have been draping thermal blankets over the glacier to insulate it from rising temperatures. This collective care has helped but won’t prevent the inevitable—the Rhône Glacier is expected to have fully disappeared by 2050. The Rhône Glacier becomes the Rhône River and is the artery that connects the Swiss Alps to the Mediterranean Sea, Europe to Northern Africa and the Middle East.

During the creation of this project, the glacier became a space for transition where its ice body took on different forms. I kept thinking about Toni Morrison’s “The Site of Memory,” where she writes: “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. It is emotional memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our “flooding.” Along with thinking about collective care as an antidote to violence and the transformation of landscapes through a visual language, the sonification of the glacier and the animal world became very important. Collaborating with sound designer Richy Carey and editor Katrin Ebersohn were such highlights—connecting the fevering glacier to sound recordings in the womb or the breaking of ice (calving) to sirens, cowbells as warning, as resistance.

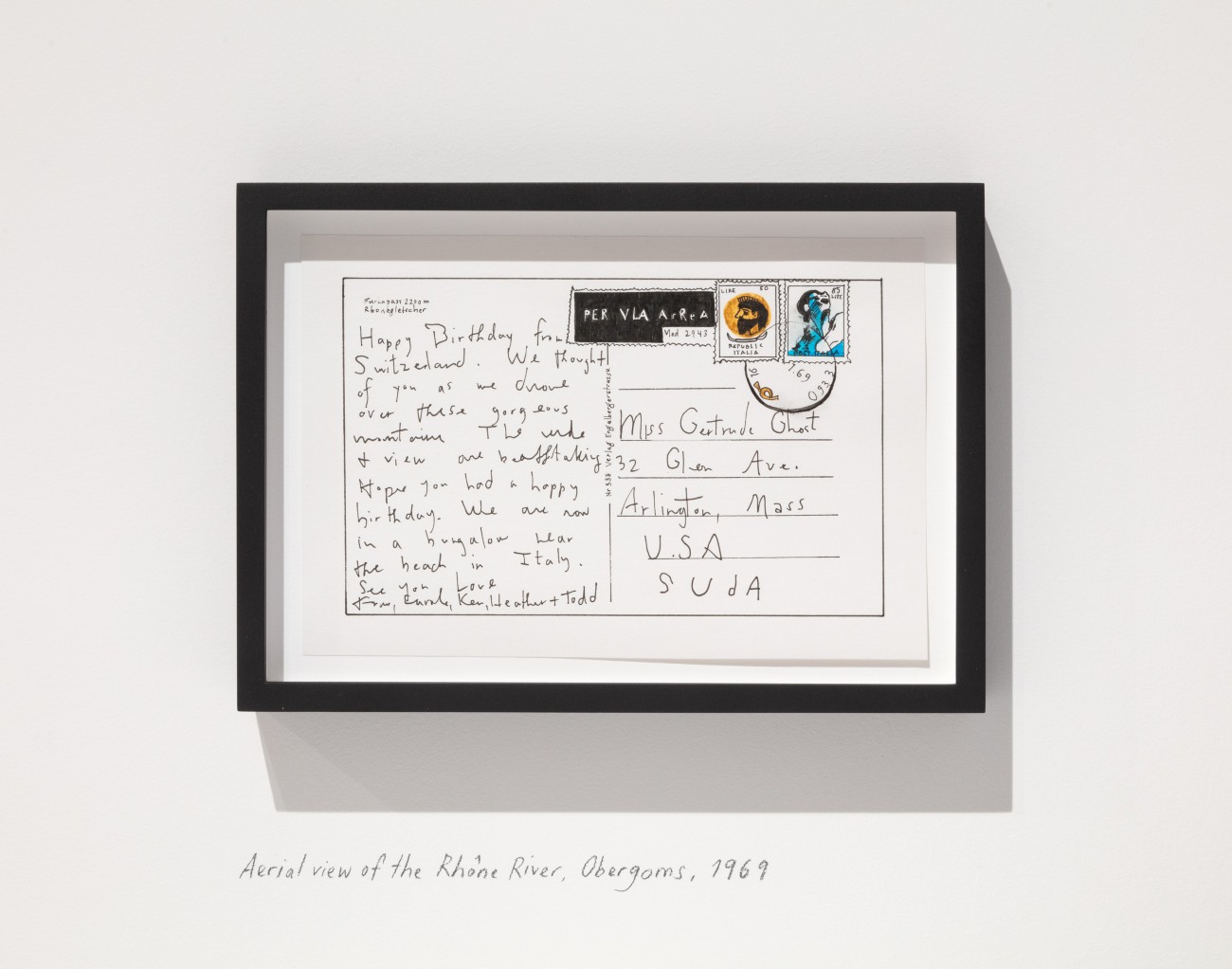

Ohan Breiding, “Souvenir 7 (Aerial view of the Rhône River, Obergoms, 1969),” 2024. Ink on paper, graphite. 4 x 6 in (drawing only). Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

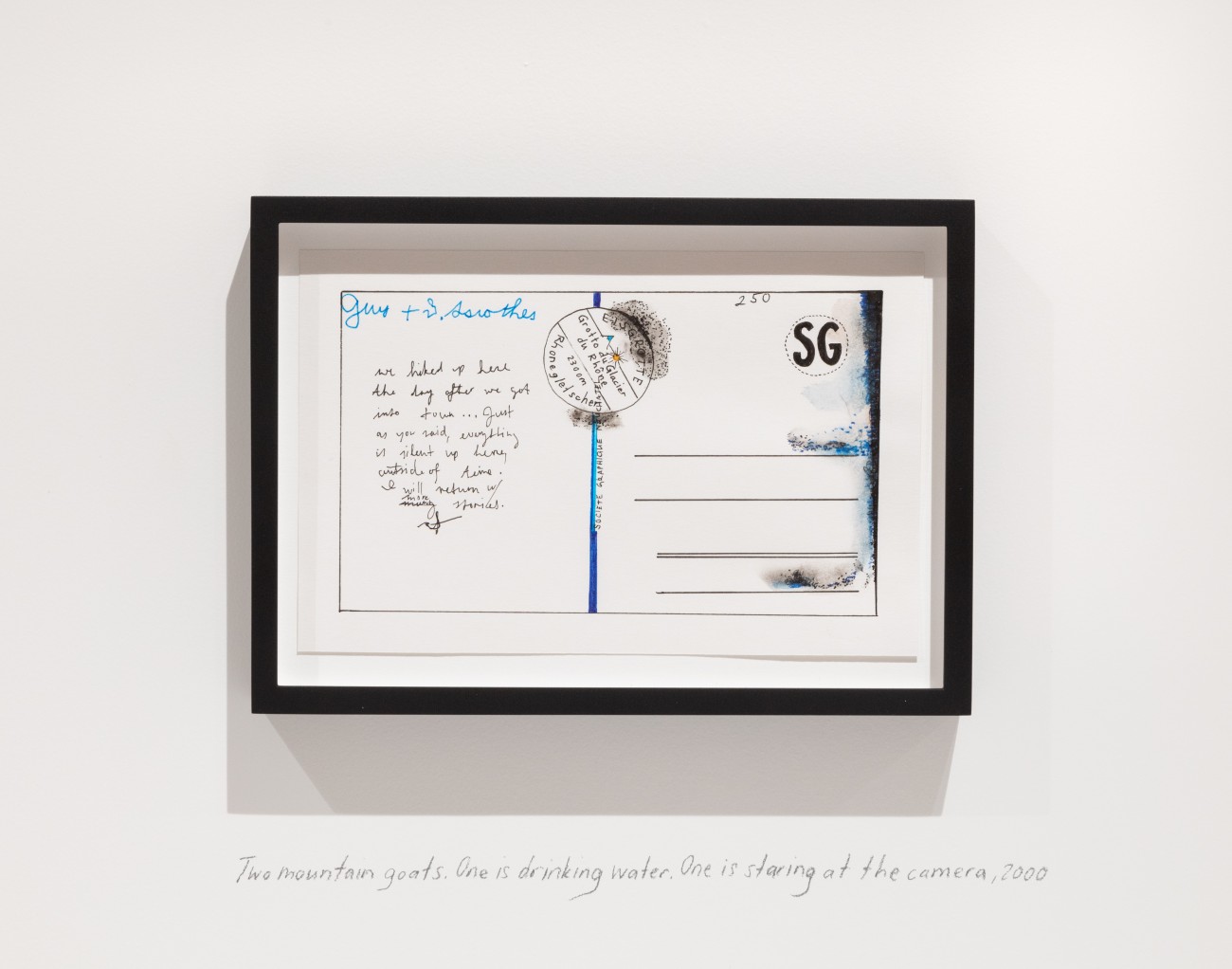

Ohan Breiding, “Souvenir 2 (Two mountain goats. One is drinking water. One is staring at the camera, 2000),” 2024. Ink on paper, graphite. 4 x 6 in (drawing only). Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

The exhibition also includes a series of postcards. Can you explain their function and how they work to solidify this story?

Alongside the film, there is also a large-scale photography installation, To dress a wound from the light that shines from it, which consists of almost one hundred unframed digital prints, varying in size and layered on top of each other. This monumental piece depicts a panorama of the glacier, including details of ice surfaces, rock formations, and animals that rely on the glacier’s water source. A hallway connects the film to this photographic installation and on those walls, there are seven intimate drawings that I made, based off of the backside of collected postcards that people wrote while visiting the Rhône Glacier from 1969-2000 and that were sent to family members and friends in the US.

The postcards act as souvenirs vis à vis the monument, the glacier. They also reference an outdated and nostalgic form of communication, a once tourism, which no longer exists in this region. These drawings were a way for me to connect with strangers and people I will never meet through an overlooked archive, who had at some point experienced a healthy glacier, the same one I experienced during my childhood. Below each postcard I describe the postcard’s backside with my own handwriting in graphite directly onto the museum wall: Stereograph of nearly two identical churches, Gletsch, 1971, A family standing on the Rhône Glacier, 1979, Two mountain goats. One is drinking water. One is staring at the camera, 2000.

Ohan Breiding, “Belly of a Glacier (To dress a wound from what shines from it) II,” 2025. Giclée prints. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI. (Photo: Jon Verney)

What do you hope people take away from Belly of a Glacier?

While many environmental discourses and exhibitions deploy statistics and doom, Belly of a Glacier looks to poetics and play, erotics and even humor while proposing an intersectional, interdisciplinary approach to ecological solidarity work. By highlighting the knowledge of ice and debris while documenting care experiments, I gesture towards trans-temporality and porous boundaries between in/animate worlds. I hope to convey the message that human, animal, and glacier bodies are interrelated and that even if a community is not within our purview, we are still collectively accountable for its well-being and futurity.

“To dress a wound from the light that shines from it (Belly of a Glacier),” 111 Giclée Prints on Fine Art Luster Paper. 128.55 in x 266.93 in or 326.5cm x 678 cm

What's next for you?

I just opened a solo exhibition at A.I.R Gallery in NYC called Beside the Sun, which features photographic and sculptural works that explore the violence of the photographic medium and resource extraction by reanimating Great Depression-era WPA (Workers Progress Administration) image archives. I specifically look at how the medium of photography, in particular the silver gelatin print, is extracted from the earth and animals; silver salts from the ground are suspended in gelatin from ungulates (horses, cows, sheep, goats, and pigs) to create a fixed image. I combine this large-scale photographic installation with delicate beeswax sculptures of earth augers (large drills) that are traditionally used to cut into the land. Of course, the beeswax material queers the form, giving a sensual smell, a softer touch, retooling the object to become something else.

In addition, I am working on a new film and photographic project titled, A letter to the future, which weaves a ritual of grief set in 2025 in the Alpine village of my upbringing, attended by local priests, politicians, midwives, medical workers and scientists with a speculative future set in 2225, where human/animal chimeras, coded to see outside Eurocentrism, have taken over Svalbard’s Arctic World Archive (AWA). There, the main protagonists act as archeologists of the future and use the historical and cultural data that has been preserved beneath the permafrost for 200 years to make sense of an absurdist Western, scientific knowledge’s past.