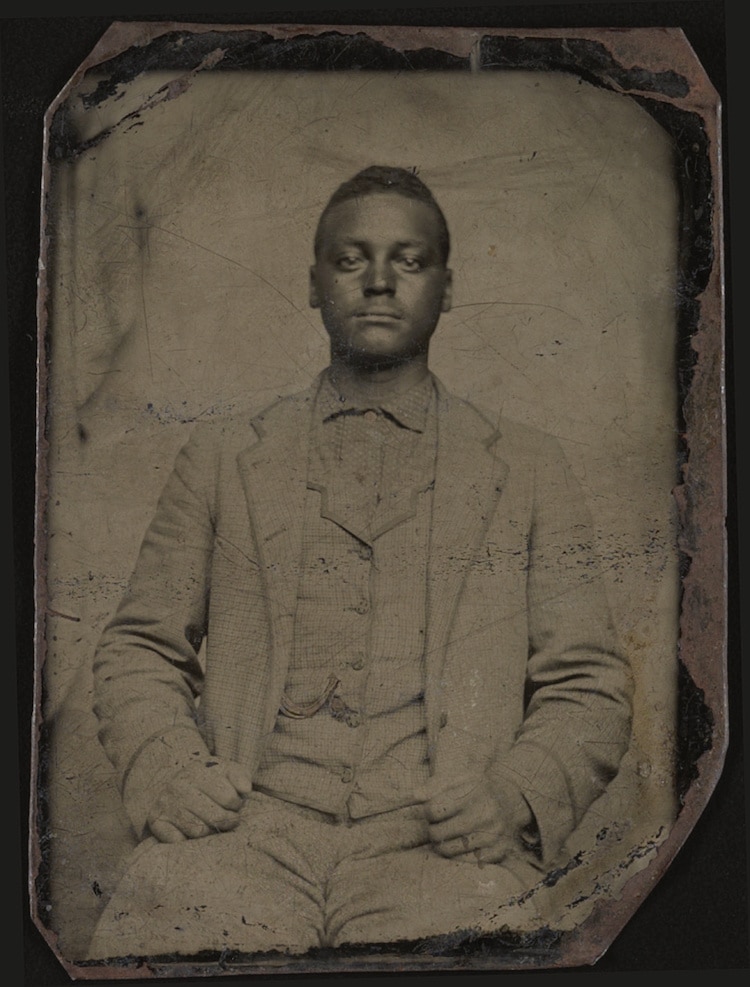

Unidentified man about 19 or 20 years old. Created 1890 and 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Today we get the instant gratification of seeing a photograph we've just taken, but the early days of photography often required long exposure times and complex developing methods before results could be seen. This all changed with the introduction of tintype photography, a process that let photographers break out of the studio and start capturing people on the street.

Tintype photography reached peak popularity in the 1860s and 1870s, but continued to be practiced throughout history and is seeing a resurgence in popularity. Contemporary photographers are taking up the method, with workshops and photography contests dedicated to tintype enjoying success. In 2014, photographer Victoria Will captured intimate tintype portraits of celebrities that caused an online sensation. With an increased taste for everything vintage, more and more people are learning to appreciate the shallow depth of field, uneven exposure, and low tonal range achieved by these images.

The style is so trendy that Hipstamatic has just released a new TinType app for iPhone that gives your digital images the old time effect. There are even companies like TinType Photo Lab that will transform digital photos into tintypes. But if you want to get your hands dirty, there are plenty of resources around to get you well on your way to becoming an expert in tintype photography. Let's look at at the history of the process and how it works before diving into ways you can start your journey into tintype photography.

View this post on Instagram

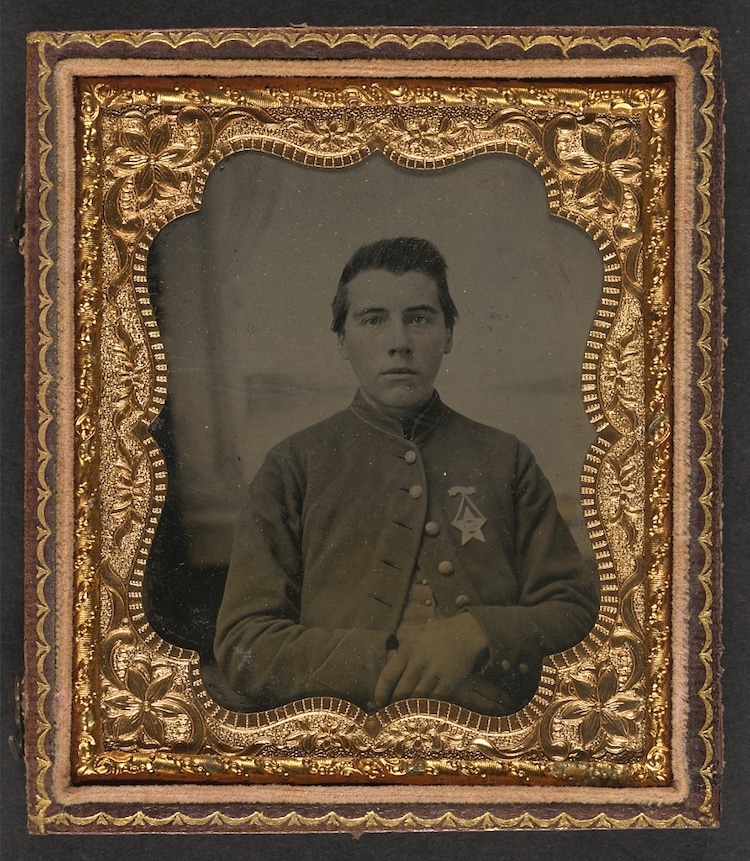

Unidentified soldier in Union uniform. Created between 1861 and 1865. (Photo: Library of Congress)

History of Tintype Photography

As the first cameras were created, a primary issue was how to make photography accessible, portable, and affordable. Daguerreotype and other early forms of photography had drawbacks due to long exposure times (which required sitters to remain completely still) and complex developing methods. The invention of tintype in 1853 by a Frenchman named Adolphe-Alexandre Martin changed all that.

Suddenly, exposure times were shortened and materials dropped dramatically in price. For the first time, photographers could take a photo and hand the image to a client in just 10 to 15 minutes. This opened the door for new types of photography. Patented separately in the United States and the UK, the process was first called melainotype, then ferrotype, and finally tintype. The name comes from the fact that the images were processed on thin sheets of metal rather than glass. Interestingly, there typically wasn't any tin involved—the plates were usually iron.

Though the resulting images were less crisp than a daguerreotype, tintype became popular with itinerant photographers. The quick processing made them a new “instant photo” and photographers would sell tintype portraits at fairs and carnivals. The invention of tintype allowed Civil War photographers like Mathew Brady to take photos out in the field. The lightweight and unbreakable nature of the photographs meant that soldiers were also able to mail portraits back to their loved ones.

Tintype eventually fell out of favor as quickly processing and developing methods were invented, but lately there's been a renewed appreciation for the time-honored technique.

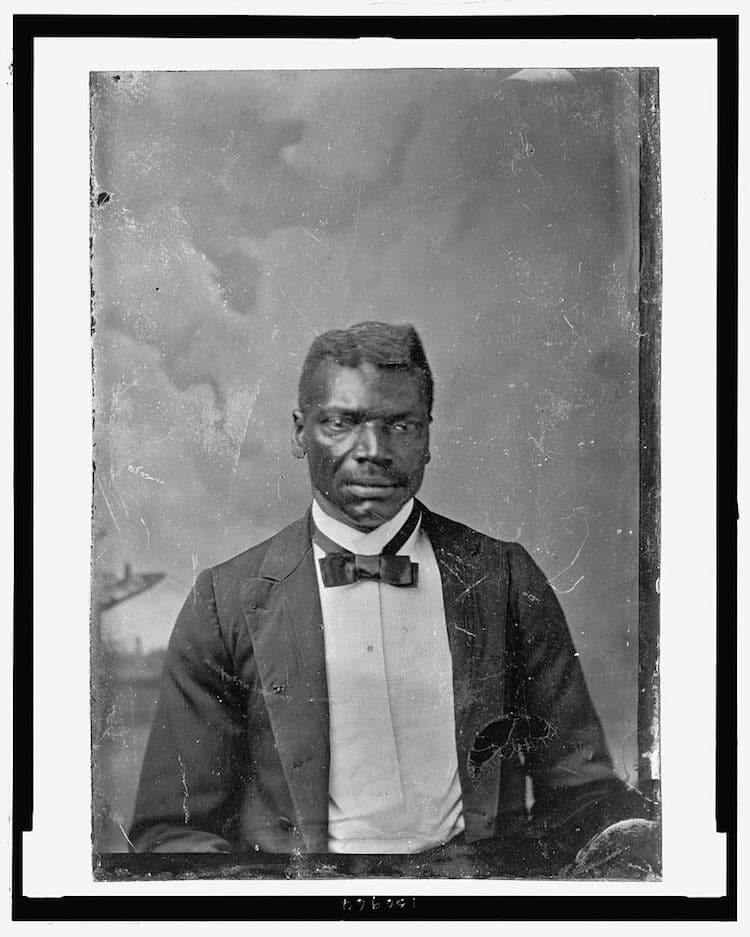

Unidentified Liberian man in suit and bowtie. Created between 1853 and 1890. (Photo: Library of Congress)

How are tintype photos created?

The original method for creating tintype photos is a wet collodion process. Collodion is a syrupy solution of cellulose nitrate in ether and alcohol. In the case of tintype, the wet collodion is applied to a thin iron plate and then covered in silver nitrate. The plate must then be loaded into a special camera in a darkroom, after which it's ready for exposure.

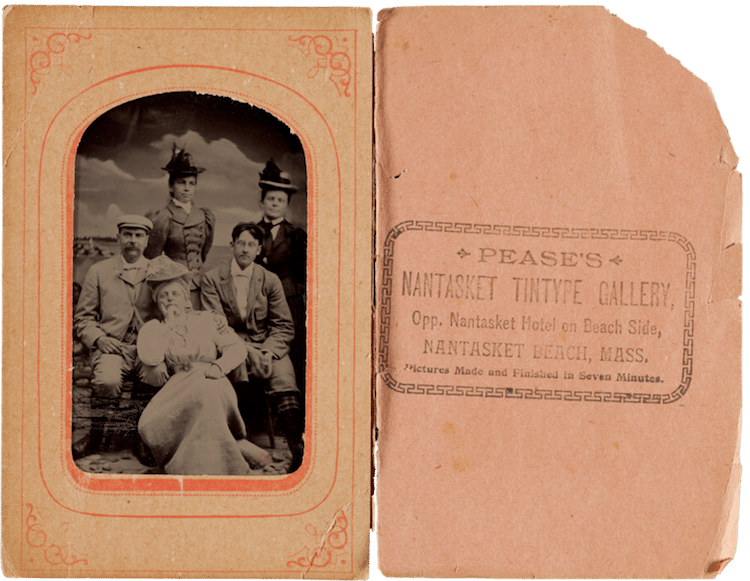

After the plate is exposed, while still wet, it must be processed immediately. The resulting image is an underexposed negative coated with dark lacquer or enamel. Once processed, photographers would either mount them in a case or placed them in simple paper mats that were perfect for carrying.

There is also a dry method, which uses gelatin emulsion in place of collodion. The plates must be prepared well ahead of time, as they need to be dry prior to usage. Whether using the wet or dry technique, the end result remains the same.

Group portrait taken at Pease's Nantasket, date unknown. (Photo: Gawain Weaver Art Conservation via Wikipedia)

Getting started with tintype photography

The boom in modern tintype photography means that there is an increasing number of resources for photographers looking to try the 19th-century technique. Modern Collodion, based in the U.S., and Wet Plate Supplies, based in the UK, both sell a wide array of supplies for budding tintype photographers.

If you're looking for a good starter kit, the Rockland Tintype Parlor Kit gives you everything you need to dive into the process. Chemical Pictures: The Wet Plate Collodion Book is another excellent resource filled with in-depth explanations of how to create many types of wet collodion photographs.

Watch this video to learn more about the science of tintype photography.