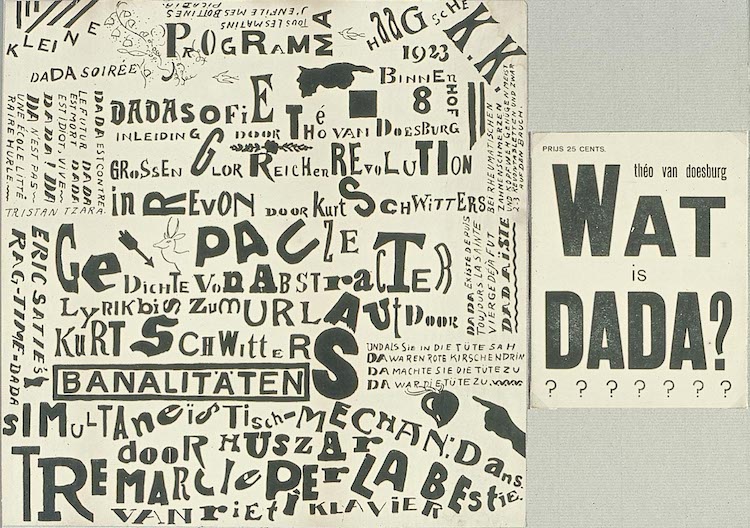

Photo: Theo van Doesburg (Public domain)

Art has been around since the dawn of time, but it's undergone many changes. Different art movements have emerged over millennia, and with them they brought inspirational artists we celebrate years later. A fairly recent style was Dadaism. Dada was a 20th-century avant-garde art movement (often referred to as an “anti-art” movement) born out of the tumultuous societal landscape and turmoil of WWI. It began as a vehement reaction and revolt against the horrors of war and the hypocrisy and follies of bourgeois society that had led to it. In a subversion of all aspects of Western civilization (including its art), the ideals of Dada rejected all logic, reason, rationality, and order—all considered pillars of an evolved and advanced society since the days of the Enlightenment.

Purporters of Dada instead embraced the absurd, chaos, nonsense, and blind chance—attributes they believed to offer a truer representation of a society that could engage in what they saw as the senseless carnage and destruction of WWI. As it was put by one of Dada’s original adherents, French-Romanian poet Tristan Tzara, “The beginnings of Dada were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust.”

The Birth of Dada and Cabaret Voltaire

During the First World War, a number of intellectuals, writers, and artists who opposed the war fled to neutral Switzerland. It was there, in Zurich, that many of them gathered during their self-imposed exiles and set the ball of Dadaism rolling. In 1916, German writer Hugo Ball—usually dubbed the founder of Dada—opened the Cabaret Voltaire with his partner and fellow Dadaist Emmy Hemmings.

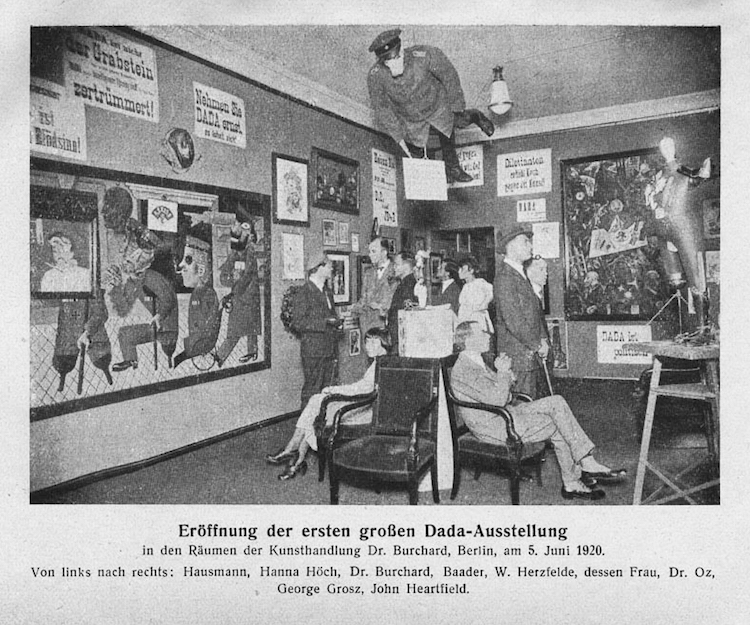

Grand Opening of Cabaret Voltaire Exhibition (Photo: Unknown author [Public domain])

Why is it called Dada?

As for how the movement got its unusual name, there are a few different explanations for how that came about. The most popular version of the story fits in quite nicely with Dada’s overarching essence. It alleges that the name was chosen by Hugo Ball and Richard Huelsenbeck when they randomly stabbed a knife into a French-German dictionary and it landed upon the word, which they deemed fitting. Tristan Tzara later claimed that he had coined the term. Some believe that it was just a nonsense word, chosen for its likeness to the first unconscious babbling of a child.

“Dada is ‘yes, yes’ in Rumanian, ‘rocking horse’ and ‘hobby horse’ in French,” Ball once wrote. “For Germans it is a sign of foolish naiveté, joy in procreation, and preoccupation with the baby carriage.” Whatever the case, it didn’t really need to make much sense.

As Dadaism grew, it spread across Europe and even to America. Many of its original members left Zurich and went to other cities such as Paris, Berlin, and New York, taking their own versions of Dada ideals and philosophies with them. Consequently, in each new place, the movement took on a different hue, becoming more political in some regions while leaning more into its anti-art aspects in others.

Dada Artists and Their Works That Characterized the Movement

Hugo Ball

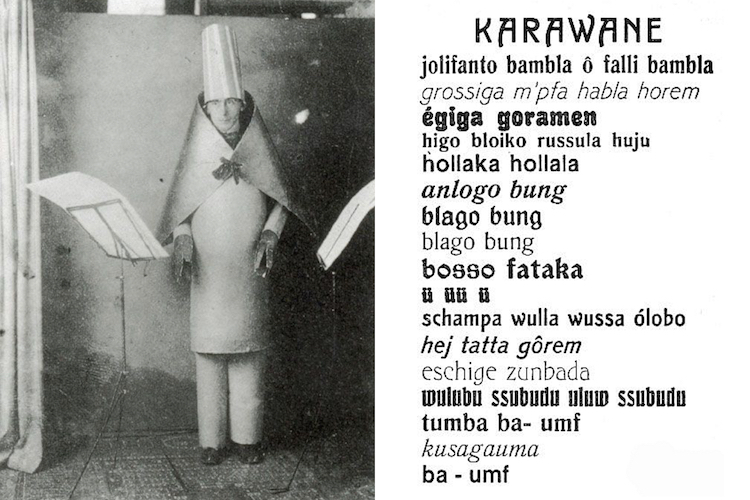

Left: Dada Artist Hugo Ball Reciting Sound Poetry at Cabaret Voltaire (Photo: Unknown author [Public domain]), Right: His first sound poem, titled “Karawane” (Photo: User Albrecht Conz on de.wikipedia [Public domain])

It will serve to show how articulated language comes into being. I let the vowels fool around. . . Words emerge, shoulders of words, legs, arms, hands of words. Au, oi, uh. One shouldn't let too many words out. A line of poetry is a chance to get rid of all the filth that clings to this accursed language, as if put there by stockbrokers' hands, hands worn smooth by coins. I want the word where it ends and begins. Dada is the heart of words.”

This new form of poetic articulation that he described was called sound poetry, and it was his primary medium of Dadaist expression. He performed the first and most well-known of these—called “Karawane”—at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916.

Tristan Tzara

“Portrait of Tristan Tzara” by Robert Delaunay (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

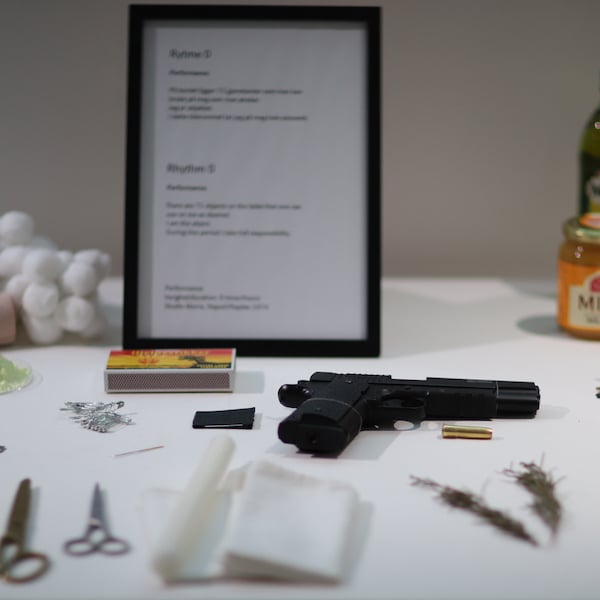

TO MAKE A DADAIST POEM

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

Jean (Hans) Arp

Jean Arp helped establish a Dadaist group in Cologne, Germany. Though he was not as deeply entrenched in Dadaism as some of his counterparts, he was one of the first artists to incorporate randomness and chance as a collaborator in his works. In one of his earliest “chance collages,” he tore pieces of paper into rough-edged shapes and then dropped them onto a larger sheet of paper, gluing them in place wherever they fell.

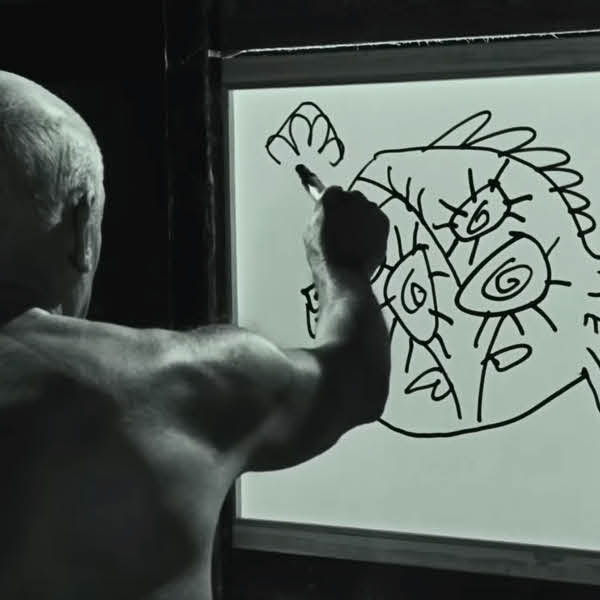

Raoul Hausmann

Raoul Hausmann was a poet, a performance artist, and also worked in collage. However, his most famous work is a sculpture entitled Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time). It consists of a manikin head made out of solid wood, with various instruments and found items affixed to it. This piece is an iconic representation and physical embodiment of Dadaist ideals, undermining the assertion that the head is the source of reason and logic. By contrast, Hausemann argued that man’s head is empty, “with no more capabilities than that which chance has glued to the outside of his skull.”

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch | Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1920

Hannah Höch was one of the very few women active in the Dada movement and one of the pioneers of the photomontage technique and collage. Her works were more serious on many levels than those of most other Dadaists. Dealing with themes of feminism and womanhood, her collages often cut with razor-sharp precision to the core of modern society’s hypocrisy and oppression of women.

Marcel Duchamp

“Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

This piece was what Duchamp referred to as a “readymade”—a common manufactured item that he would then sign, date, and display in a gallery, therefore declaring it a work of art. By doing this, he raised many concepts that questioned long-held views on what constitutes art. Duchamp’s larger purpose was to shift away from what he called “retinal” art, or art made for the eye, to a new form of art that is created for the mind.

What Happened to Dada?

The Dada movement was destined to be short-lived, seeming to have programmed its own self-destruct button at its very conception. “Dada is anti-Dada” was even one of the group’s oft-used mantras. By the early 1920s, Dadaism was slowly fizzling out as its primary players scattered across the world and moved on to other pursuits. However, despite its brief trajectory, Dada marked a crucial and pivotal moment in 20th-century art and culture, and its lasting influence can still be seen in many of the artistic styles and movements that followed—long after its own swift demise.

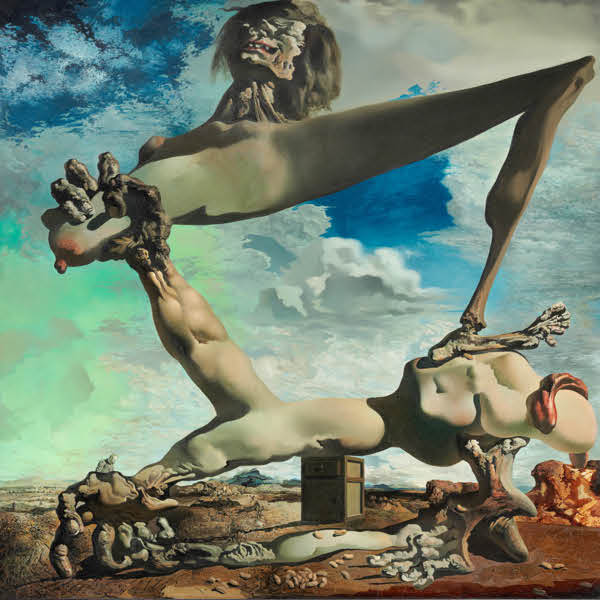

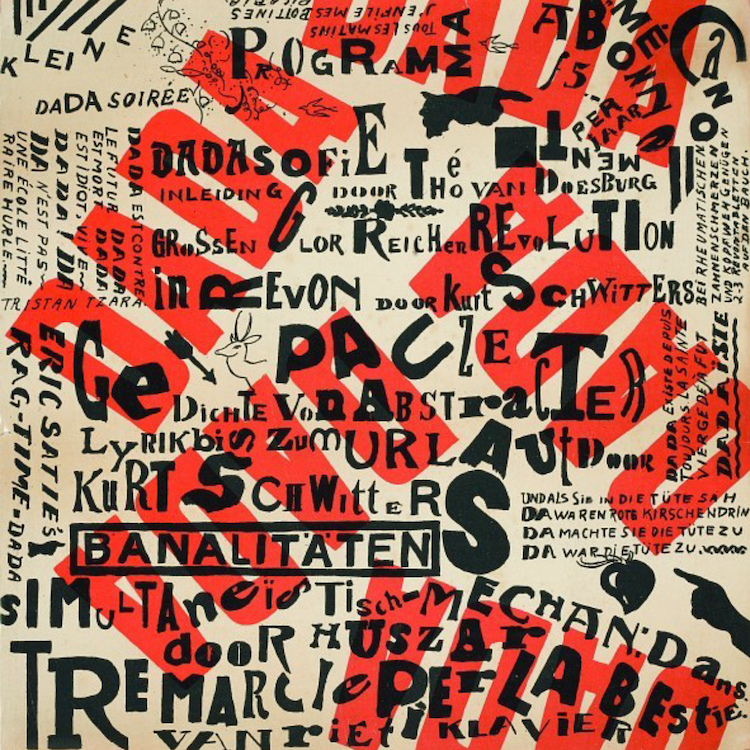

Artist: Theo van Doesburg (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Dada’s influence can even be seen outside of the visual arts. Many critics have associated its influence with the birth of rock music of the 70s and the punk movements that later followed. Others have acknowledged the foundation that Dadaist visuals might have laid for much of today’s internet visual culture, especially memes.

Though this anti-art, art rebellion took place about 100 years ago, it is still incredibly relevant. Perhaps now more than it has been in quite a while.