Photo: Gorodenkoff/Depositphotos

When thinking about prehistoric men and women, there are longstanding stereotypes. Men used to go out and hunt large creatures, while women gathered food—a clear-cut division of labor based on sex. However, the latest research points out that this was not entirely true. Not only did some women hunt as well, they also possessed certain physical traits that may have made them better hunters than their male counterparts.

These findings were shared by Cara Ocobock, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology and director of the Human Energetics Laboratory at the University of Notre Dame. As a human biologist studying physiology and prehistoric evidence, she found that many of the ideas regarding early humans–especially those pertaining to males being biologically superior—weren't looking at the big picture. “This was what everyone was used to seeing,” Ocobock said. “This was the assumption that we’ve all just had in our minds and that was carried through in our museums of natural history.”

With the help of Sarah Lacy, an anthropologist with expertise in biological archaeology at the University of Delaware, Ocobock found that not only did prehistoric women did practice hunting, but their anatomy and biology would have made better at it. But how so? Well, according to Ocobock, the female body is better suited for endurance activities due to the higher levels of two hormones, estrogen and adiponectin. By modulating glucose and fat, they enhance athletic performance—like running animals down into exhaustion before actually going in for the kill.

Additionally, the female anatomy has features that could have contributed to their hunting strength. “With the typically wider hip structure of the female, they are able to rotate their hips, lengthening their steps,” Ocobock explained. “The longer steps you can take, the ‘cheaper’ they are metabolically, and the farther you can get, faster. When you look at human physiology this way, you can think of women as the marathon runners versus men as the powerlifters.”

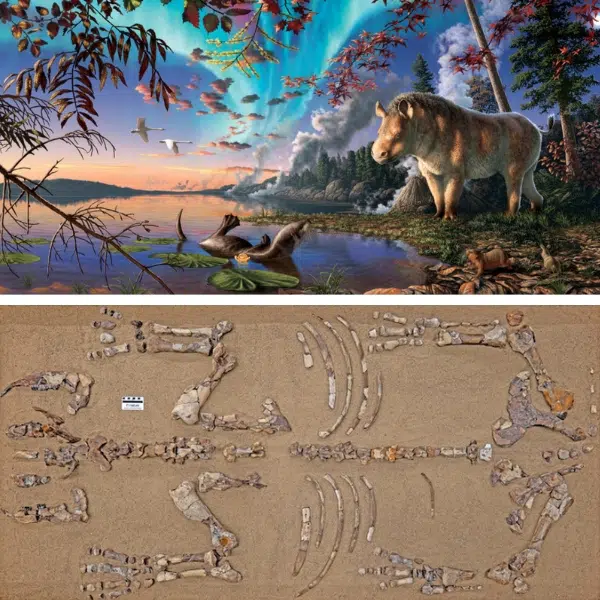

Lacy and Ocobock also found archaeological evidence that supports their theory. Female hunters from the Holocene period in Peru have been found buried with hunting weapons. “You don’t often get buried with something unless it was important to you or was something that you used frequently in your life,” Ocobock said.

The injuries sustained in both prehistoric female and male bodies also speak of enduring similar activities. “We have constructed Neanderthal hunting as an up-close-and-personal style of hunting, meaning that hunters would often have to get up underneath their prey in order to kill them,” Ocobock added. “As such, we find that both males and females have the same resulting injuries when we look at their fossil records.” These include head and chest injuries from being kicked by an animals, bite marks, and fractures. “We find these patterns and rates of wear and tear equally in both women and men,” she said. “So they were both participating in ambush-style hunting of large game animals.”

Ultimately, they both hope their findings challenge the notion of a “female physical inferiority” and gender biases. Ocobock concluded, “Rather than viewing it as a way of erasing or rewriting history, our studies are trying to correct the history that erased women from it.”

The latest research points out that not only did some prehistoric women hunt, breaking a longstanding stereotype, but they also possessed certain physical traits may have made them better hunters than their male counterparts.

Photo: Gorodenkoff/Depositphotos

Arguments include the presence of higher levels of estrogen and wider hip structure, as well as the finding of ancient women buried with their spears.

Photo: Gorodenkoff/Depositphotos

h/t: [IFL Science]

Related Articles:

Rare 1885 Photo Captures the First Licensed Women Doctors of India, Japan, and Syria

Archeologists Discover 1,500-Year-Old Mayan Palace in Mexico

10 Fearless Women From History Who Fought for a Better Future