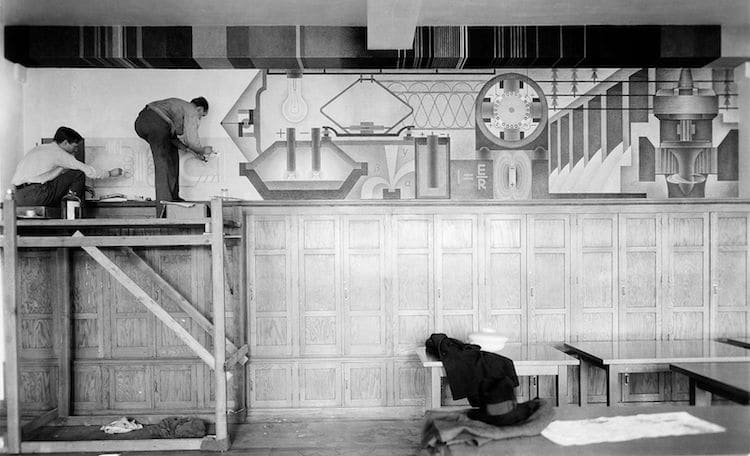

Photograph of artist Eric Mose on scaffold with mural “Power” at Samuel Gompers Industrial High School for Boys, Bronx, New York (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

“I pledge you, I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people,” he proclaimed in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1932. Four months later, FDR would win the election by a landslide, and by 1933, he would launch his New Deal, a series of policies and programs intended to put the country on a streamlined path toward relief, reform, and recovery. With an emphasis on employment, the New Deal's primary goal was to put people to work, whether through low-interest loans to farmers, large-scale construction assignments, or even a creative Federal Art Project.

The Federal Art Project

Logo of the Federal Art Project (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Art

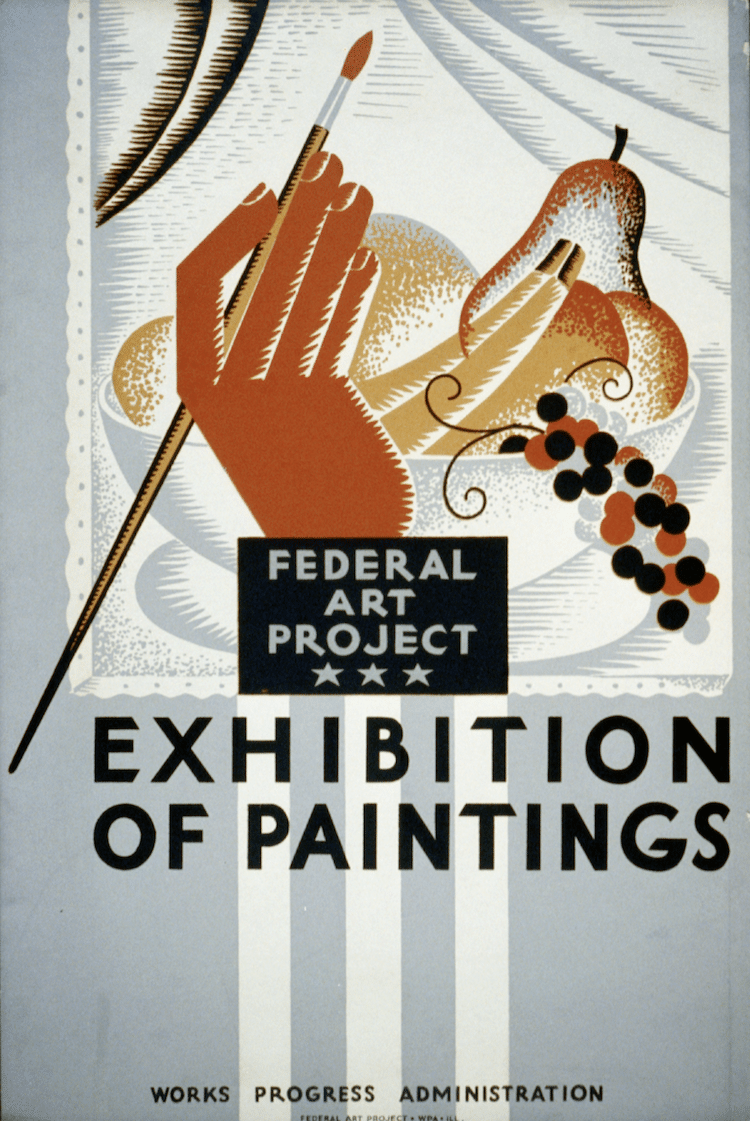

“Exhibition of Paintings” Poster, ca. 1936-1941 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

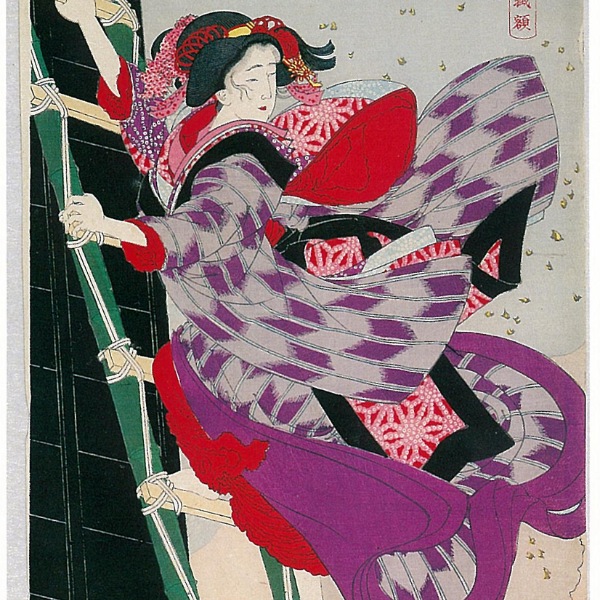

The Federal Art Project, however, focused on enlisting out-of-work artists to produce graphic posters, documentary photographs, large-scale sculptures, modernist murals, and other works of art (namely for municipal and public buildings, but also for theaters, museums, and other arts organizations). It also called for community art centers to pop up across the country, serving as exhibition spaces, educational institutions, and as a much-needed means of making art accessible to all.

“I, too, have a dream,” FDR said, “to show people in the out of the way places, some of whom are not only in small villages but in corners of New York City—something they cannot get from between the covers of books—some real paintings and prints and etchings and some real music.”

Artists

Sculpture workshop in New York sponsored by the Federal Art Project, C. 1940 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

What set the Federal Art Project apart from these initiatives, however, is that it employed artists of all skill levels and backgrounds. “The organization of the Project has proceeded on the principle that it is not the solitary genius but a sound general movement which maintains art as a vital, functioning part of any cultural scheme,” Cahill explained in 1936. “Art is not a matter of rare, occasional masterpieces.”

This inclusive approach to employment proved successful. By the end of its first year, the Federal Art Project employed over 5,000 artists. By 1943, this number doubled, culminating in hundreds of thousands of artworks.

Record numbers of employment and high quantities of output, however, were not the only positive outcomes offered by Cahill's hiring practices. With little focus on upholding traditional notions of talent, the Federal Art Project inadvertently fostered some of modern art's most groundbreaking artists. In 1940, African American painter Jacob Lawrence would break boundaries with his colorful Migration Series, while Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko would found the Abstract Expressionist movement just a few years later.

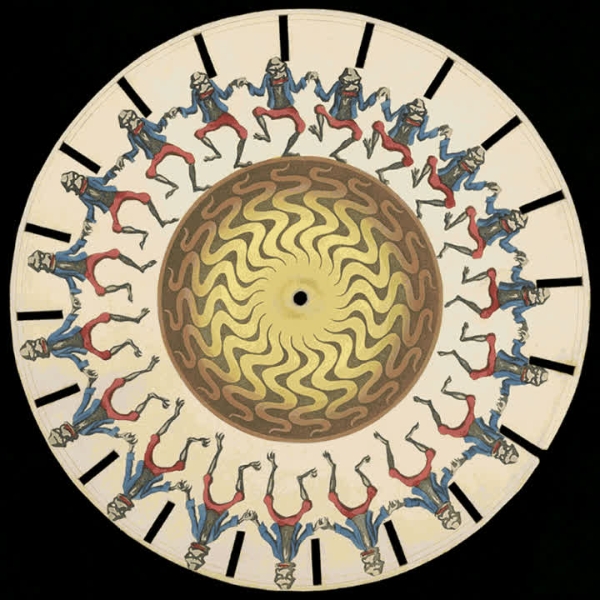

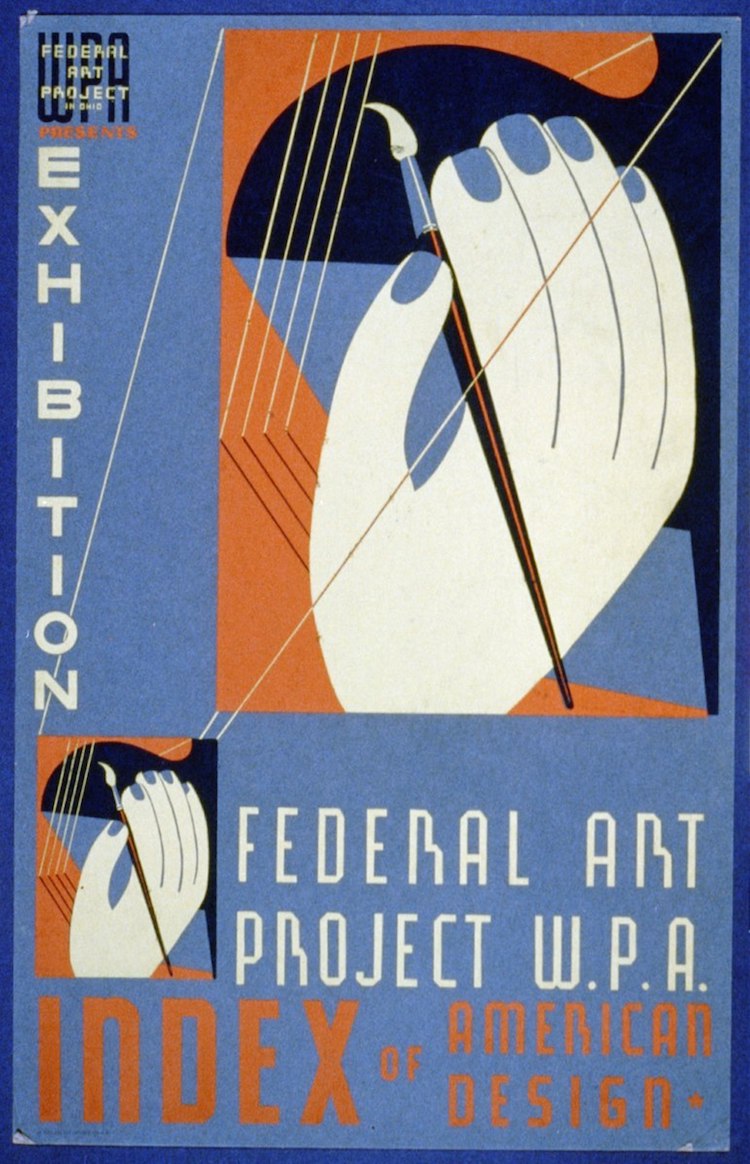

Poster for Federal Art Project exhibition of “Index of American Design,” ca. 1936-1938 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

“As we study the drawings of the Index of American Design we realize that the hands that made the first two hundred years of this country's material culture expressed something more than untutored creative instinct and the rude vigor of a frontier civilization,” Cahill explained. “The Index, in bringing together thousands of particulars from various sections of the country, tells the story of American hand skills and traces intelligible patterns within that story.”

The Project's Legacy

The Federal Art Project continued employing artists until 1943—four years after the termination of Federal Project Number One and the end of the Great Depression. At its conclusion, Holger Cahill was still director, having overseen the impressive completion of roughly 2,500 murals (many of which still adorn the walls of public buildings), 18,000 sculptures, 108,000 paintings, 22,000 plates for the Index of American Design, and countless ephemera.

While these works are considered federal property, many of them have seemingly disappeared, whether unaccounted for in non-federal repositories or simply lost. Since 2001, however, the U.S. General Services Administration has been diligently working to track down any misplaced or missing works, taking inventory and compiling a readily available resource for “museum professionals, the academic community, art conservators, and the public at large.” So far, the agency has recovered and cataloged 20,000 irreplaceable pieces, culminating in a legacy that is stronger than ever before.

Related Articles:

The Story Behind the Iconic ‘Migrant Mother’ Photo that Defined the Great Depression

How African American Art and Culture Blossomed During the Harlem Renaissance

How Diego Rivera Shaped Mexican Muralism, a 50-Year Movement Sparked by the Revolution

9 Abstract Artists Who Changed the Way We Look at Painting

Precisionism: The Modern American Style Sparked by Industrialization