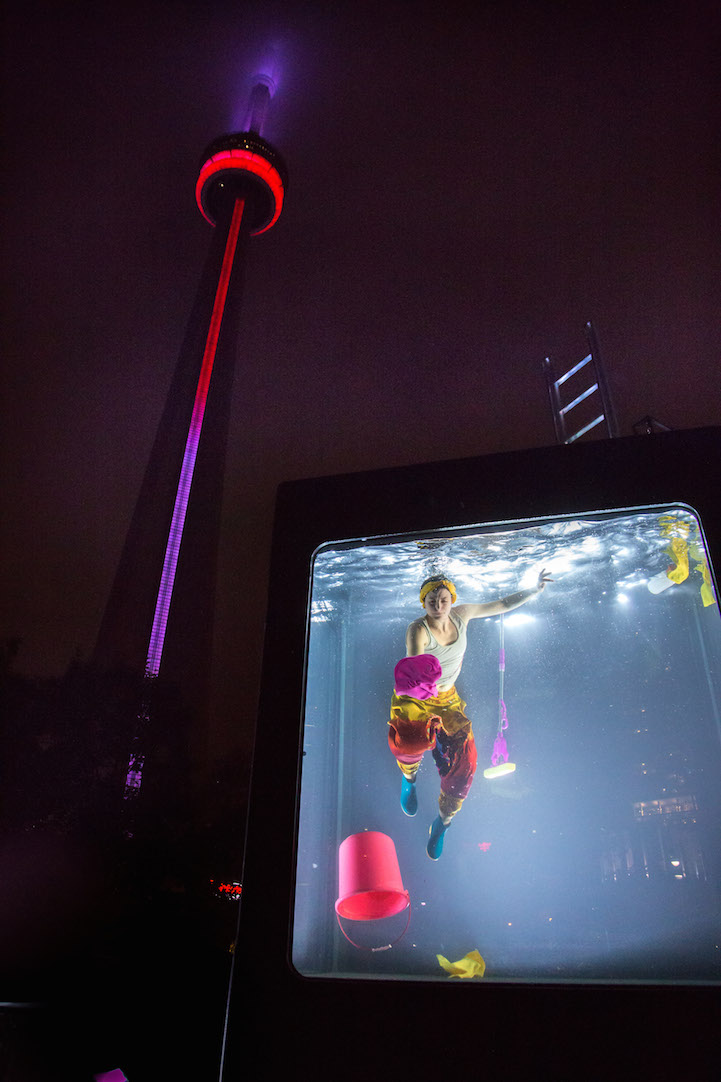

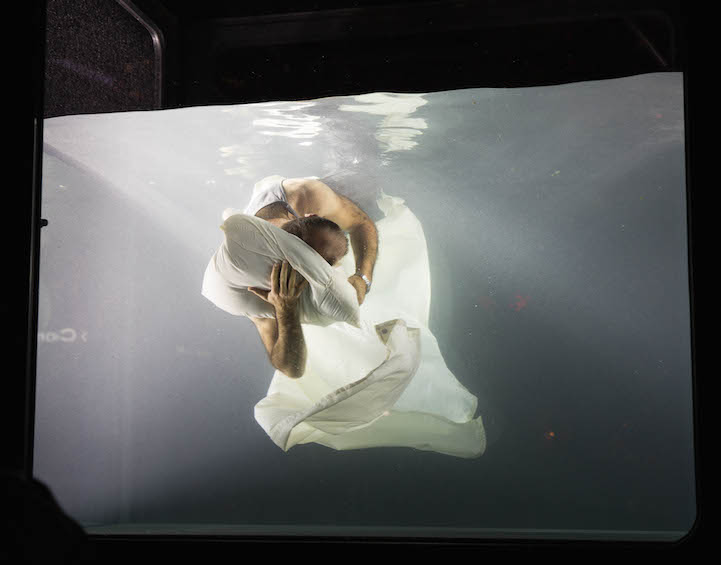

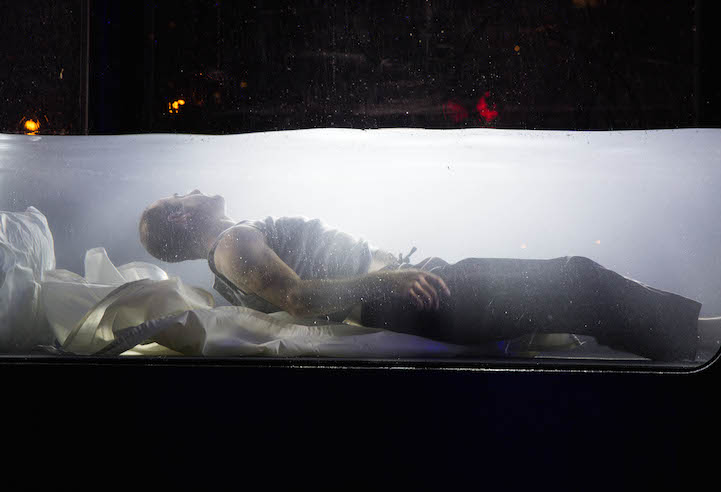

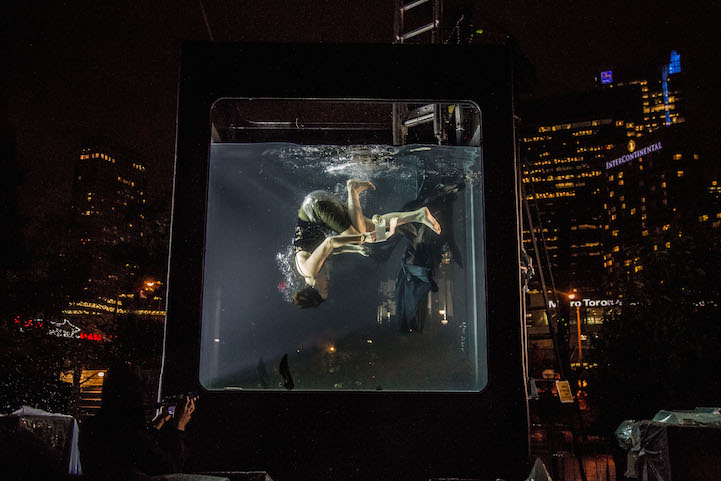

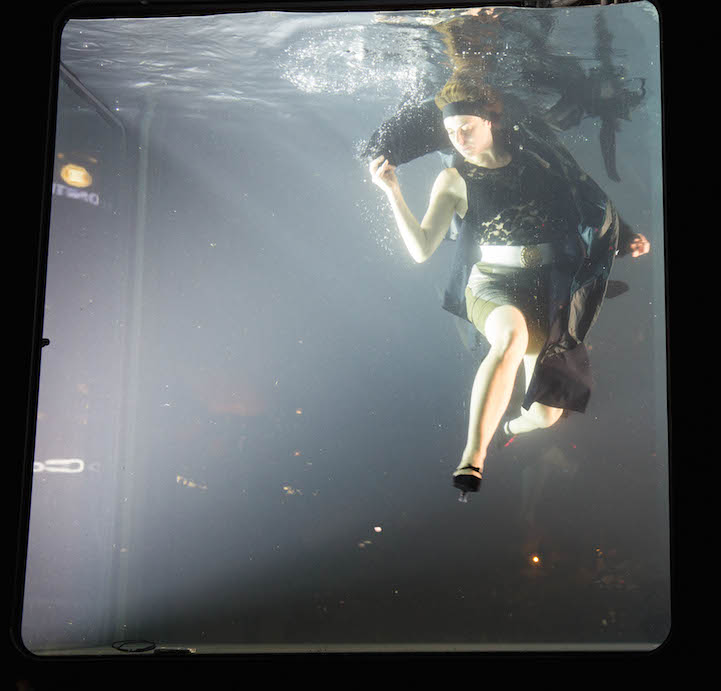

What would everyday life look like if Earth was flooded by rising seas, melting glaciers, intensifying floods and droughts? HOLOSCENES is a thought-provoking performance installation by artist Lars Jan that visually answers this question. “The ebb and flow of water and resulting transformation of human behavior offers a portrait of our species' collective myopia, persistence and, for better or worse, adaptation,” explains Jan. It is a “visceral, visual and public collision of the human body and water.”

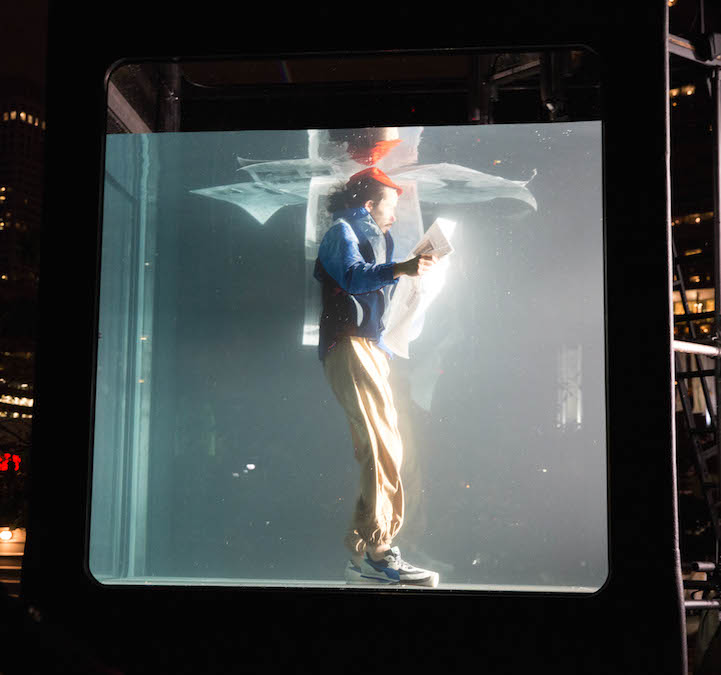

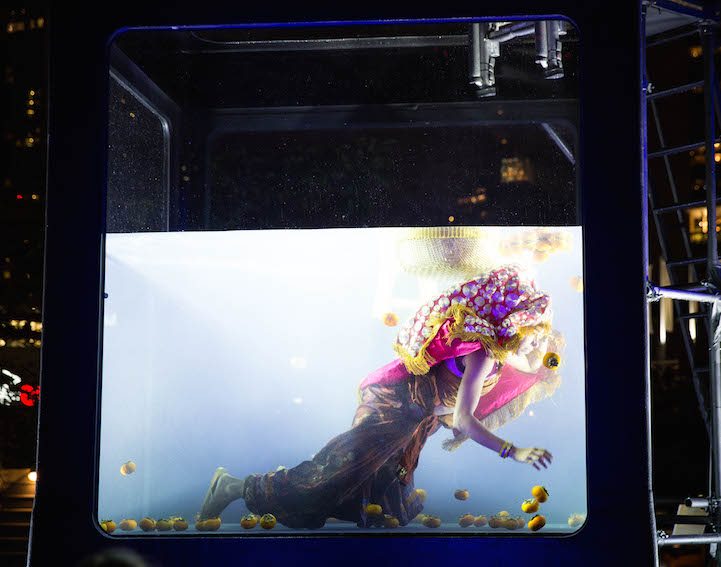

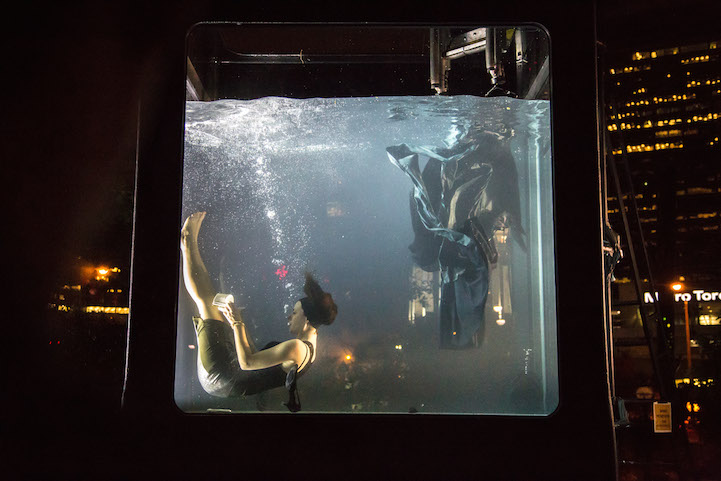

The large aquarium is viewable from 360 degrees and, for over 12 hours, several performers take turns in the aquarium for about an hour each, conducting a variety of mundane yet poetic behaviors such as reading a newspaper, washing windows, or trying to falling asleep.

Filled and drained by a custom, programmable hydraulic system, the aquarium floods with up to 12 tons of water in less than a minute, deluging the performer within. As the water rises, the performer swims to the top like a whale gasping for air and then dives back down to adapt their behavior to the new aquatic environment. A submerged hydrophone transmits sounds of movement and churning water to the audience.

Lars Jan is a director, writer, artist, and founding artistic director of Early Morning Opera, a performance + art lab, whose works explore emerging technologies, live audiences, and unclassifiable experience. I had the pleasure of meeting Lars at Scotiabank Nuit Blanche in Toronto. Check out my interview with him, below.

Can you please give us a little bit of background on yourself and Early Morning Opera?

I'm a director, writer and visual artist, and I live half the year in Los Angeles, and the other half in Brooklyn. My parents emigrated from Afghanistan and Poland, and met in Cambridge, MA. I mostly grew up around there.

I direct Early Morning Opera, a performance and art lab that is an ever-expanding network of frequent and new collaborators, including people working within and beyond the arts. We research and develop multi-disciplinary projects over several years, and often these works are influenced by my early background as an activist. Our works have been commissioned and presented by places like the Whitney Museum, Sundance Film Festival, and BAM Next Wave Festival, and funded my many national, state, and private philanthropies including the NEA and Rauschenberg Foundation. But, we couldn't have created HOLOSCENES on our own – at the outset we partnered with the incredible producers MAPP International Productions, who helped us work at this scale in terms of resources and complexity.

What inspired you to create HOLOSCENES?

By 2010, I felt increasingly aware of a string of devastating floods, and images of people around the world struggling through deep, turbulent water were haunting my thoughts. One in particular, captured by photo journalist Daniel Berehulak during the flooding in Pakistan, was so simultaneously beautiful and horrific that I began thinking a lot about beauty as a delivery mechanism for despair, and as a route to empathy.

Around that time I had an intense daydream over about 60 seconds in which a man in was in a big glass room trying to read a newspaper, but suddenly the room started to flood with water fast. But he didn't panic, or even acknowledge the water rising over his head; he just turned the page, and kept reading. Soon the paper dissolved in his hands, but still, he just kept reading the nothing that was in his hands.

At that moment, I had no idea that this image would be the seed of the next three years plus of my work and imaginative life. I have lots of small visions not unlike that one, but most are just part of the day to day, and I forget them shortly after they appear. But, for whatever reason, I can't shake some images for months, and at some point I recognize that's the case and that's how I decide on my next project. The man holding a nothing-newspaper while the floodwaters rose around him was like that.

You mentioned that you envisioned HOLOSCENES evolving over time. How do you see it evolving?

From the early stages, I imagined HOLOSCENES as a multi-platform project, in part because I knew the performance installation itself would be too logistically complex present everywhere I would've wanted, but also because various formats are better suited to the different conceptual threads within the project.

I've almost completed a series of circular light-boxes – called light circumferences – featuring photos I captured during the HOLOSCENES development process, as well as a video installation. These will be exhibited for the first time at the Pasadena Museum of California Art in the first half of 2015.

I'm also working towards a second suite of photographs – a process I began during the premier in Toronto, and will continue during the upcoming performances at the Ringling Museum of Art and Yerba Buena Center of the Arts in 2015. I'm also trying to figure out how to gather the resources to shoot a feature-length film in the tradition of Koyaanisqatsi.

The performance unfolds in public space and is mostly wordless, so it doesn't really allow for text to be transmitted. It's a visual and visceral experience, which is how I wanted to make the broadest audience possible feel something about what they were seeing, but also compel them to immediately ask themselves: What is this about?

They're free to answer that question for themselves, but I'd like to create a book – that appears to be badly water damaged – as well as newsprint handouts, to be available as resources for folks interesting in learning more about the thinking that went into the project, and shedding some light on the multi-disciplinary process and group of collaborators responsible for HOLOSCENES.

All that should take me to 2017 or so. I'll be making new works and exhibiting existing ones during that span, but I'm sure that I'll be developing various components of HOLOSCENES for many more years.

What is the message you are trying to present through your installation?

Well, I don't want to limit what HOLOSCENES is about. One of my favorite parts about the project is how open it is.

That said, something I've learned myself through this project is that climate change is a mirror. It's more about us – the behavioral and cognitive science behind how we make decisions, think in the long-term, and feel empathy – than it is about CO2 or melting glaciers.

What was your impression of Scotiabank Nuit Blanche this year? What does the event represent to you?

Coming from the US, I find it extraordinary that a city is the producer of an annual art event operating at this scale. Frankly, I wish we had a similar festival in New York or LA or elsewhere in the US, but we don't as yet – at least not that I know of.

I was in awe of the patience and integrity of the team of producers and technicians working with us, and have to admit that I don't quite know how we could have premiered anywhere else – they gave us a three week residency in advance of Nuit Blanche itself, and so they helped develop the project in addition to presenting it. For a project of this scale, that's a unique commitment, so I feel very lucky and grateful to them.

Photo credit: Sue Holland and Eugene Kim

Holoscenes at Scotiabank Nuit Blanche's website

Early Morning Opera