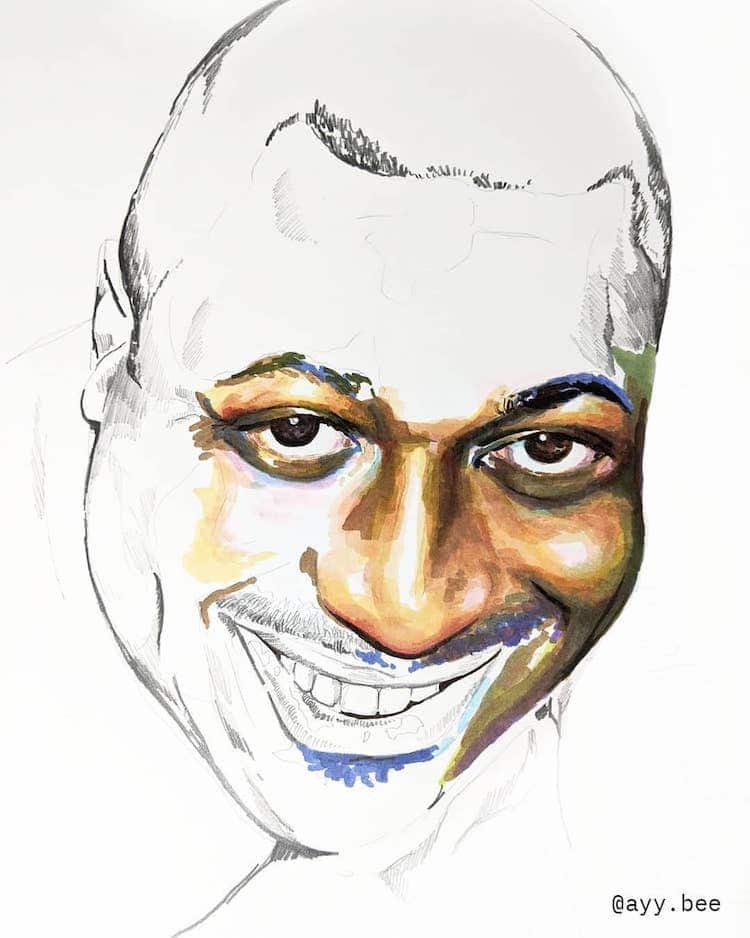

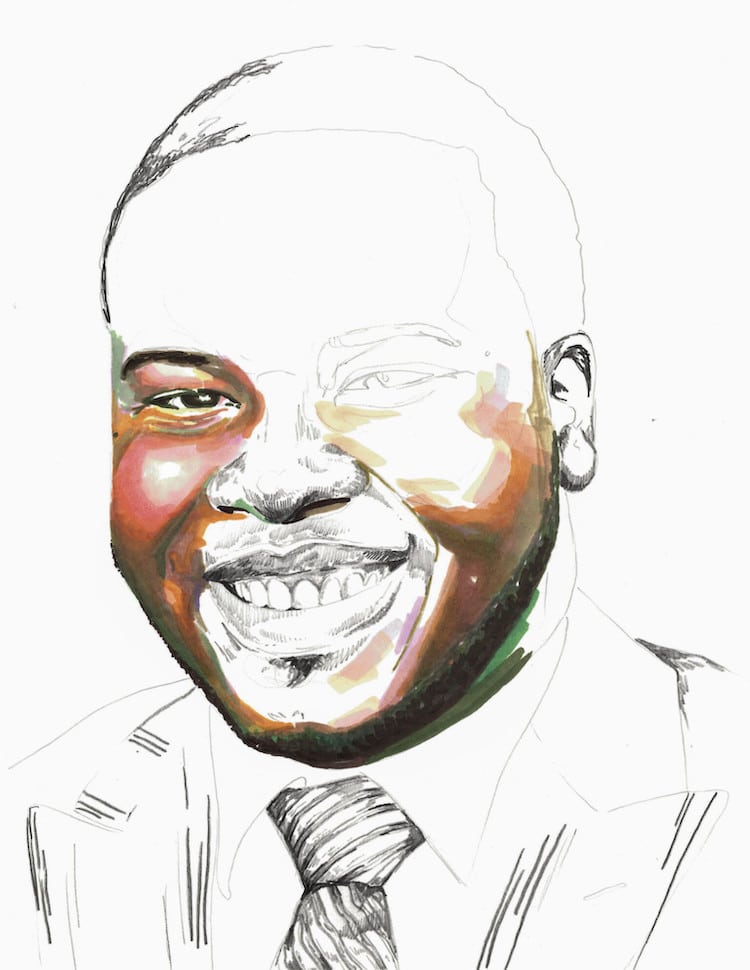

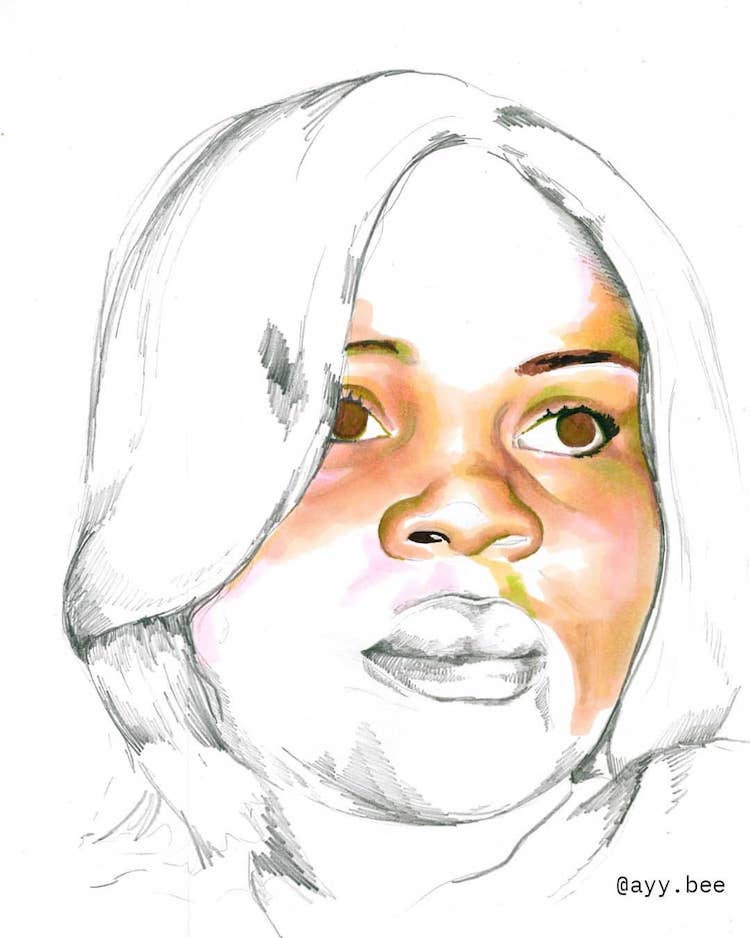

George Floyd. 46 years old, 46 minutes of color

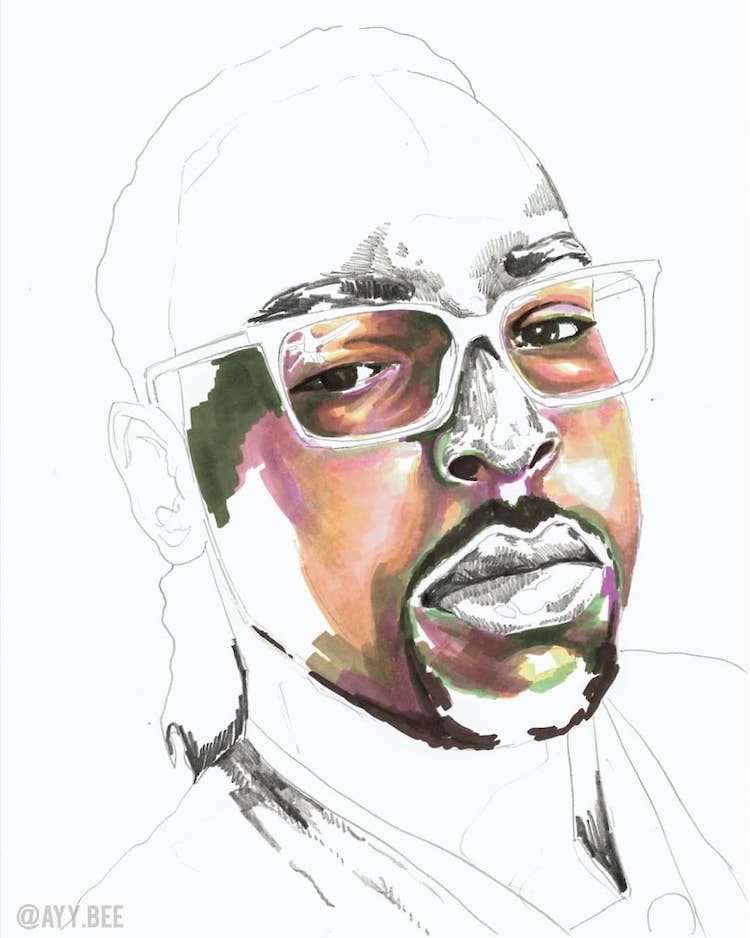

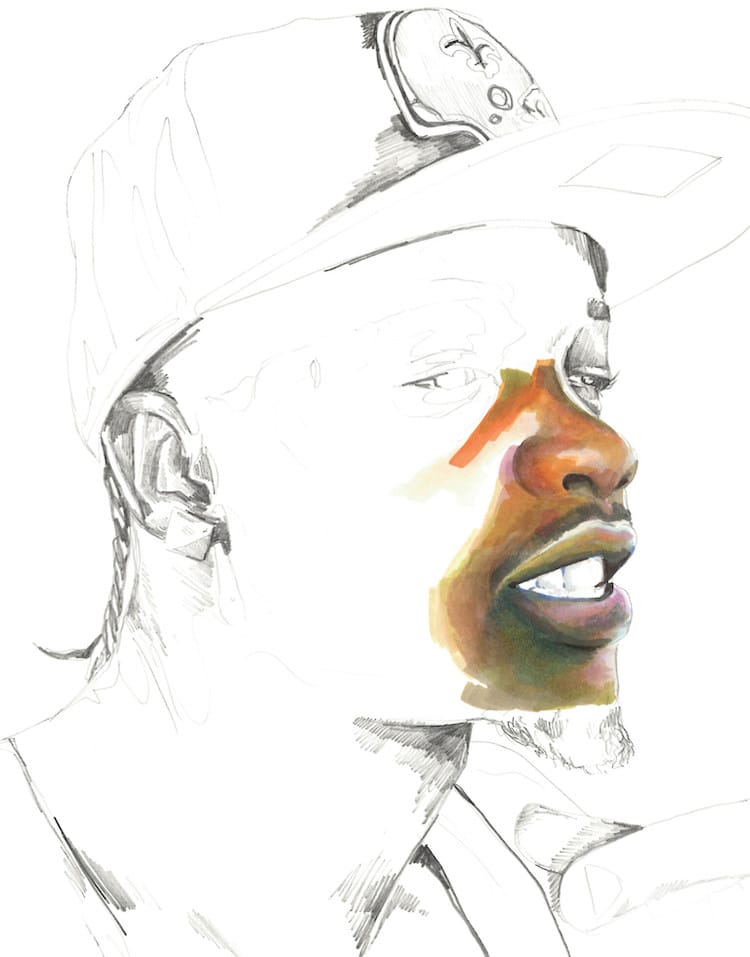

Artist Adrian Brandon creates work that focuses on the Black experience. While part of this centers around the “unique joy, swagger, and love” that is shared in the community, Brandon also uses his talents to mourn the Black people who have been killed by police. Through his ongoing series called Stolen, Brandon draws portraits of the many men, women, and children whose lives were tragically cut short. Their likenesses are first rendered in pencil and then the Brooklyn-based artist uses markers to color the portrait for the years they were alive, in which one year equals one minute of color.

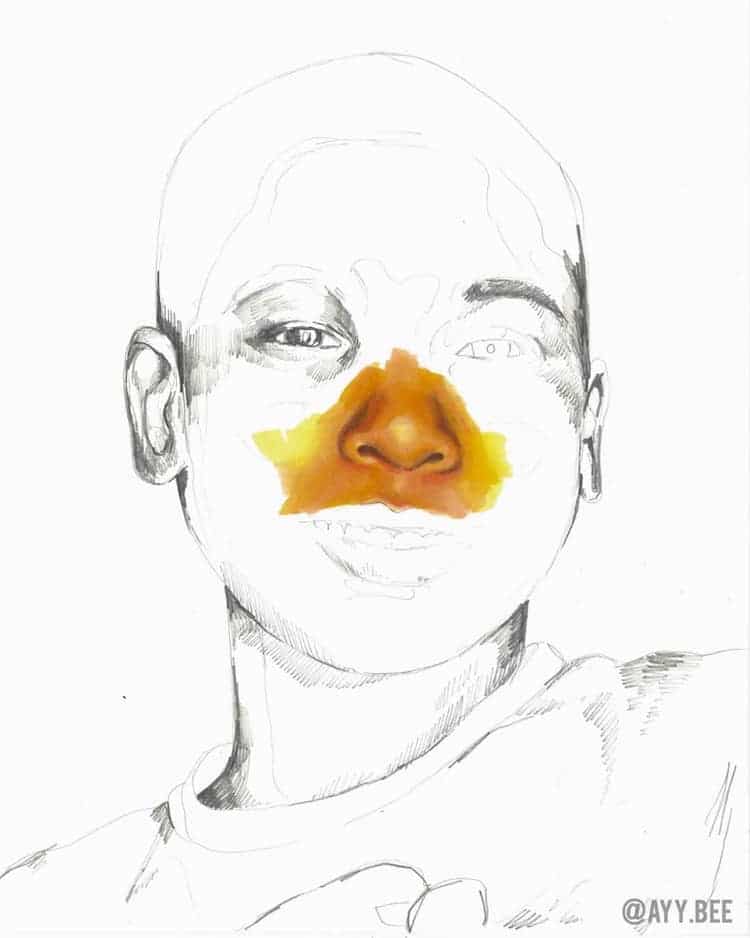

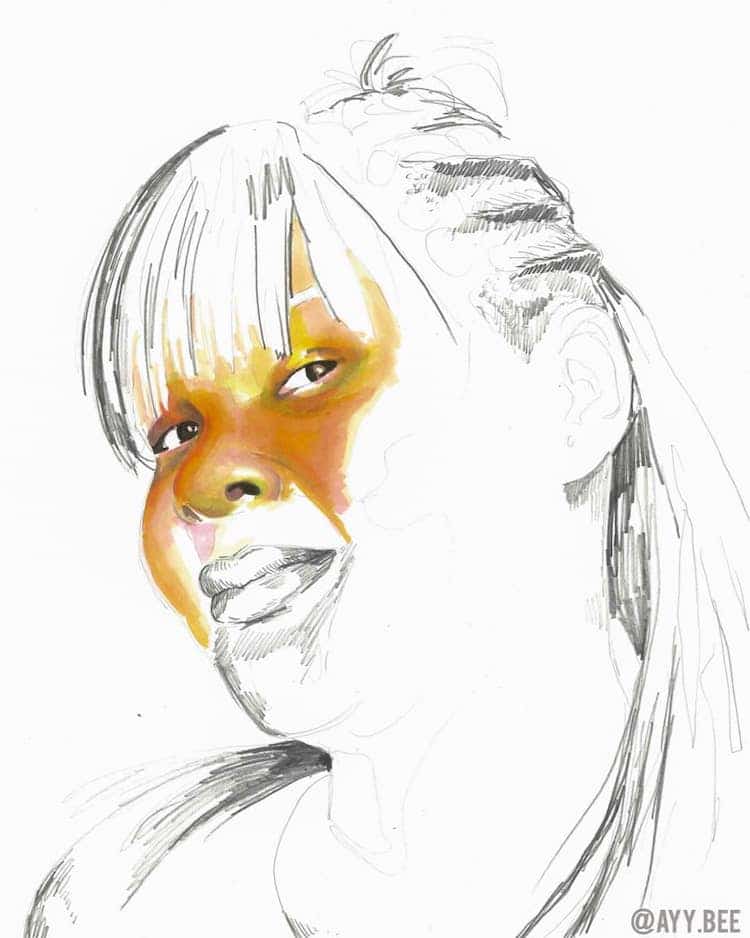

George Floyd, whose death sparked worldwide outrage and protests, was counted down from 46 minutes. Other victims have only a fraction of that time; Tamir Rice was just 12 years old when he died, and that gave Brandon only enough time to have the center of his face colored.

The incomplete portraits force us to contemplate what has been lost in the death of these individuals. They are powerful and devastating reminders that these people won’t celebrate another birthday or participate in life’s milestones, from finishing school to getting married. “This emptiness represents holes in their families and our community,” Brandon explains, “who will be forever stuck with the question, “who were they becoming?”

We spoke with Brandon about Stolen and the role that art making has in expressing our humanity. Scroll down for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

Tamir Rice. 12 years old, 12 minutes of color

What's your artistic background?

As a family, we used art as a way of showing love and celebrating each other. Every Mother’s and Father’s Day included handmade menus for brunch. I slept on a bunk bed that was decorated with paintings and poems by my mother, illustrating a world in which my siblings and I ate pancakes all day on Planet FILA. We played GI Joes in a room with doors covered in murals of our father lifting us up and carrying us on his shoulders, and I ate Wheaties cereal on a hand-painted stool customized just for me, every morning. With this being my foundation for creativity, drawing has always been something I’ve loved.

Sandra Bland. 28 years old, 28 minutes of color

Breonna Taylor. 26 years old, 26 minutes of color

How did you get into drawing and portraiture?

In school, I was the kid in class filling the margins of each page with doodles, creating years worth of my best art on lined notebook paper. In high school, although sports were my primary extracurricular focus, I had an art teacher named April Ferry who saw more in me than just an athlete. I continued pursuing art at Pitzer College where I learned how my art can spark a real conversation about injustices in the world, and it wasn’t until 2017 that I began focusing on portraiture. That year, for Black History Month, I highlighted Black leaders that are alive and enriching Black culture today—Black History in the Making. I taught myself how to paint with markers and fell in love with the depth I could achieve through layering and blending colors.

Eric Garner. 43 years old, 43 minutes of color

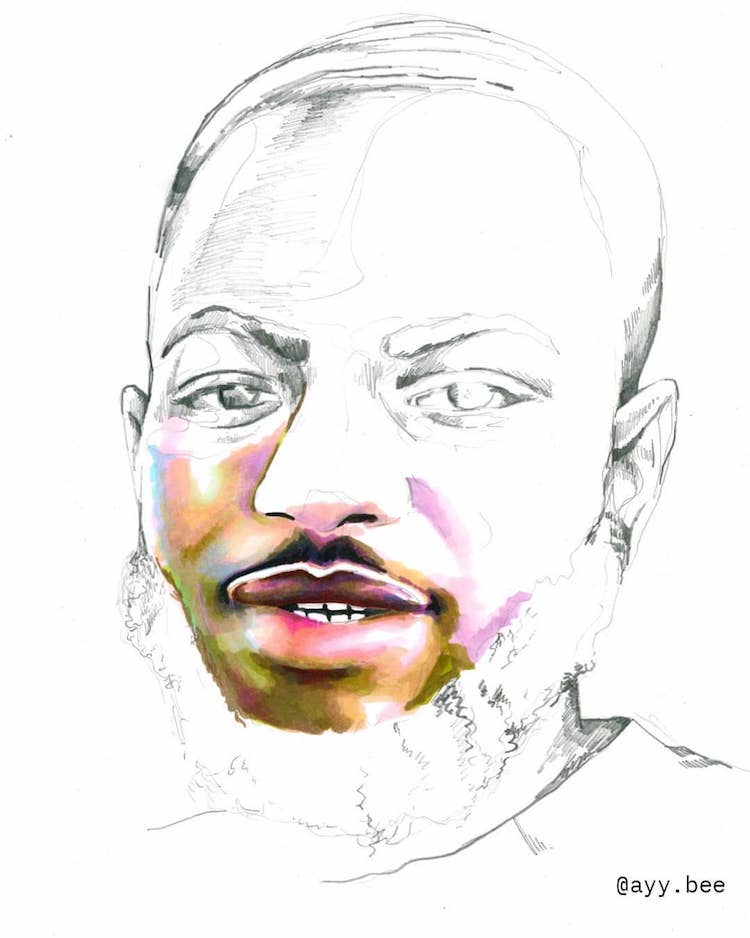

Ryan Twyman. 24 years old, 24 minutes of color

How did you come up with the concept—relating time and color—for the Stolen series?

As a Black man in today’s society, the fear of police violence against the Black community is always present in my mind. A broken taillight, a hoodie, or simply playing with friends can cause the end of our life. In late 2018, Jemel Roberson had just been killed and his story was fresh on my mind; he was only one year older than me when his life was stolen. I needed a way to show how many Black lives are taken by police because the hashtags weren’t working. One day, as I was working on a commission of a 92-year-old Black man who had passed away (from natural causes), I shared the work in progress with my girlfriend. We talked about how oddly beautiful the piece looked even though it wasn’t complete—how the empty space stirred questions. I often think while working on commissions of the deceased: What were they like? How did they carry themselves in the world? How did they die? I reflected on how fortunate he was to live a long life, and how not all Black people are given that much time. With all of this in mind, Stolen was born.

View this post on Instagram

To watch you add color to your portraits for only a short period of time adds another level of emotion to this series. What is it like working in this way, knowing what the minutes ticking by mean?

It’s stressful and it’s heavy. I started the Stolen Series in February of 2019, and after several months I had to step away from it and give myself space to grieve. Each time I start coloring a new piece there’s a sense of panic. I want so badly to color in as much as I can… to finish this eye, to get to the lips. When the timer goes off there’s anger, deep sadness, and a sense of hopelessness. The fact that so many people are resonating with these portraits has made me feel so much more hopeful. People of all skin colors are feeling the same despair I feel when I create them, and recognition of that loss is so important as we fight for change. Some family members have also reached out and thanked me for creating a portrait of their loved one; for keeping their name and story alive. That has made such a difference in how I feel as I create new portraits. Honoring these lives is so important to me. So while creating these portraits takes an emotional toll on me, I find peace in the fact that I’m spending time with them and learning their stories. I’m mindful that the pain I feel is nothing like the pain the families feel, and I’m humbled to honor these stolen lives and use my skills to amplify their stories.

Aiyana Stanley-Jones. 7 years old, 7 minutes of color

Botham Jean. 26 years old, 26 minutes of color

In these portraits, the uncolored space holds so much meaning. What does the emptiness mean to you?

The emptiness symbolizes the unknown. All the questions that their loved ones are now faced with. All the milestones and celebrations that will never be had. It represents the hole that is left in the hearts of their communities. The desire for more. The painful truth that their story was unfinished.

Rekia Boyd. 22 years old, 22 minutes of color

Philando Castile. 32 years old, 32 minutes of color

You've said you feel rushed to create these pieces, knowing that the time is running out. How does this relate to the larger experience of Black people?

Stress. Anxiety. Fear. These are feelings far too familiar for Black people in the United States, and history has made it so. The timer represents the uncertainty; the randomness that Blacks live with every day—not knowing if this is the day that something you do or say or wear might end your life. For parents, it’s the worry that your daughter might play her music too loud outside the 7-11, or your son might reach for his wallet when the police pull him over instead of keeping his hands on the wheel as you’ve taught him. These fears are so real and so prevalent for Black families. Minor transgressions can cost a life. We’re exhausted.

Akai Gurley. 28 years old, 28 minutes of color

What kind of response have you received from Stolen so far?

So far, people have been incredibly receptive to Stolen. Lots of people are using the series as a way to begin a conversation about the Black Lives Matter movement with their peers. Art teachers have reached out from all over the world expressing their excitement to use the series in their curriculums focusing on art as a tool for change. Strangers have really opened up to me about the visceral reactions they have felt. Right now, we are seeing a lot of content on social media about the injustices that need attention, and this series is doing just that, but in a visual language that is unique and heartbreakingly simple.

In November of 2019, I featured Stolen at my first solo art show in New York City. In attendance were the family members of Akai Gurley, an unarmed Black man who was killed in a stairwell in Brooklyn in 2014. I colored his piece for 28 minutes. I was deeply moved by the conversation I had with his family. They expressed their gratitude for the series and how nice it felt to see other people still thinking of Akai. This is what the series is all about to me, to show the families that their loved ones are not forgotten and to raise awareness of the common threads that tie all these lives together.

Tony McDade. 38 years old, 38 minutes of color

What role do you think art-making plays in expressing our humanity?

Art has the ability to pull us in through feelings and emotions. It invites us to be vulnerable and can transcend politics and party lines, giving us a more universal reach. Art speaks to the heart and keeps our humanity out front. Given the fight before us, that’s important. We can’t lose sight of the fact that this is about human lives. Sure, policy and systems need to change. That’s critically important. But this isn’t just a revolution to be waged by policymakers and legislators. This fight is about human lives and art helps us remember that.

In addition to Stolen, you have other series of works including Brooklyn Windows, which is about COVID-19. What else are you working on now, and what do you have planned for the future?

Right now, most of my focus is on Stolen. I am seeking ways to have Stolen experienced in person because it holds so much more power when you are confronted with a wall of faces looking back at the viewer. My show last year proved that and unfortunately there have already been so many additional lives added to the series.

When I am not creating pieces for Stolen, I am creating work that celebrates Black culture. Black people are flooded with imagery of Black pain, suffering, and loss, and I want to counter that with reminders that our skin is something to celebrate. That our love is powerful. That our durags are really just superhero capes.

Atatiana Jefferson. 28 years old, 28 minutes of color

Adrian Brandon: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Adrian Brandon.

Related Articles:

Fairytale-Inspired Portraits Reimagine Disney Princesses as Regal Young Black Girls

Quilted Portraits Honor the Stories of Black Men and Women Who Are Forgotten by History

15+ Black-Owned Businesses Selling Creative Products to Support

Street Artists Around the World Are Paying Tribute to George Floyd