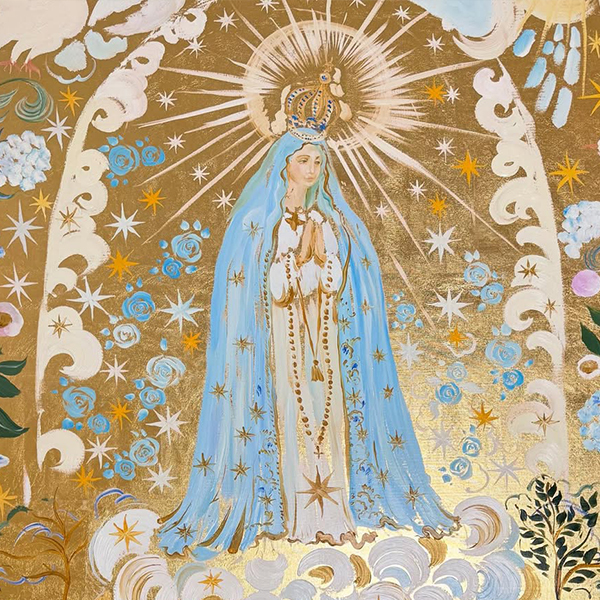

“Welcoming the New Dawn,” mixed media on Evanston municipal ledger, 18 x 36 inches, 2018

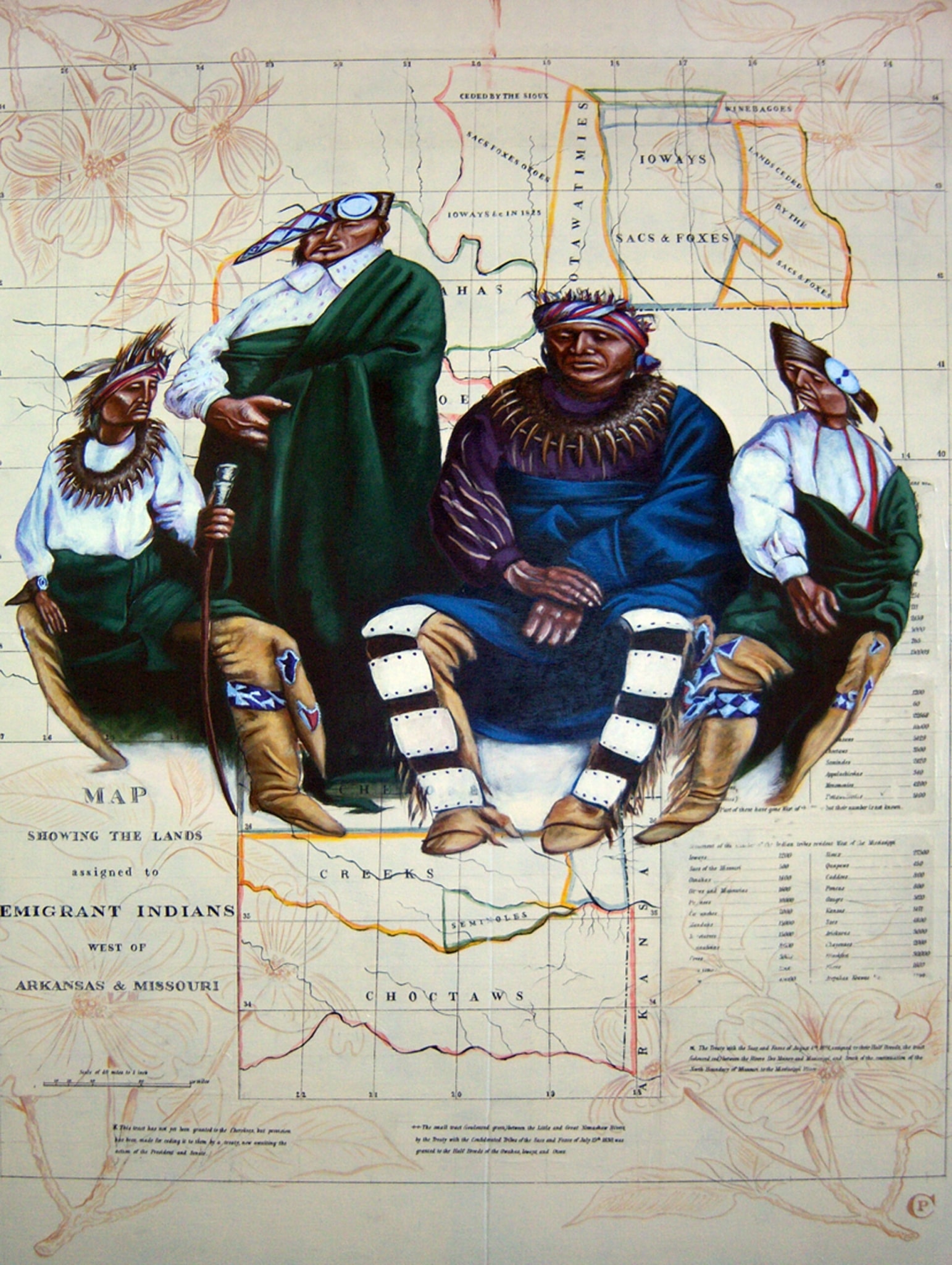

Ledger art emerged in the mid-1800s as a way for Native American people of the Great Plains to preserve their culture when American settlers were moving westward. Chicago-based artist Chris Pappan is carrying on this tradition with his multimedia portraits of different Native figures on historical documents.

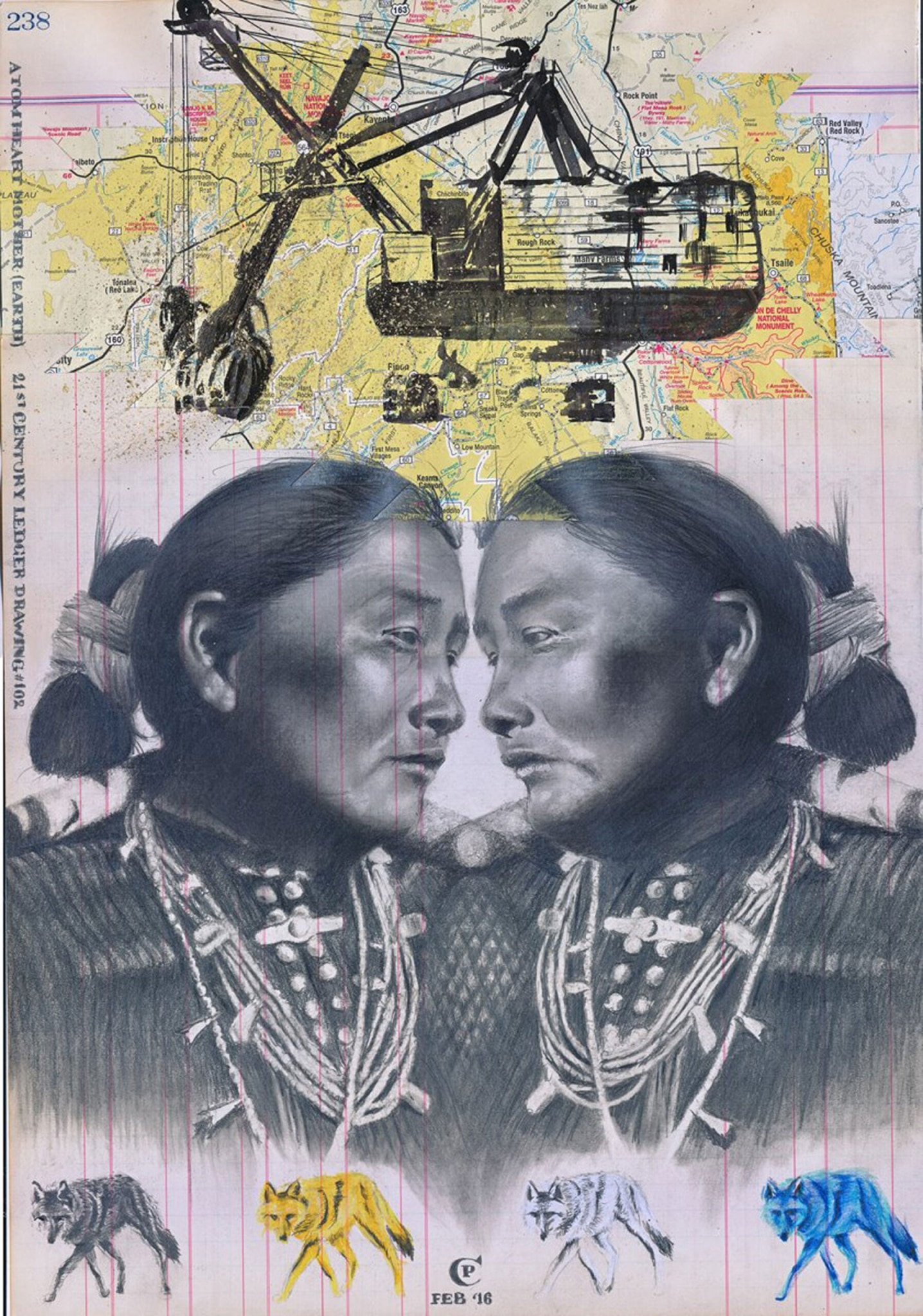

“As our people were forced onto reservations and into prison camps, the ledger paper was an available resource to visually record the way of life that had been decimated,” Pappan—who is a citizen of the Kaw (Kanza) Nation and of Osage, Lakota, and mixed European heritage—tells My Modern Met. “I see my work as part of that continuum or our culture; as reinforcing our existence and reinforcing our contemporaneity.” He uses an array of different materials, like colored pencils, graphite, and ink to sketch realistic renderings of mirrored individuals on 19th-century ledgers. Oftentimes, these figurative drawings are accompanied by collages of vintage maps, which act as ledgers of stolen lands.

Pappan's mixed-media practice involves more than just ledgers, though. His series of mirrored portraits on Boy Scouts of America neckerchiefs comment on the systemic racism embedded in the youth organization and its misappropriation of Indigenous imagery.

We had the chance to chat with Pappan about his ledger art and how his practice upholds traditions from generations ago. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Left: “Quantum,” mixed media on embossed Evanston municipal ledger, 36 x 18 inches, 2020 | Center: “Land Acknowledgement Memorial,” digital image, public art multi-city installation, 2019 | Right: “Of White Bread and Miracles (Shield,” mixed media on Evanston municipal ledger, 36 x 18 inches, 2020

How did your journey in art begin?

I have always been an artist. Starting out as we all do at a very young age, I just kept at it through high school, then attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. After moving to Chicago, I did a short time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. For almost 20 years, I worked for a commercial art gallery which I think really helped me to understand the “business” of art. In 2018, the gallery closed and I’ve been a full-time artist ever since.

Can you tell us about the tradition of ledger art and how it plays a role in your practice?

Ledger art came about in the mid-1800s as America was expanding westward (Manifest Destiny) and introduced paper as an artistic substrate to the people of the Plains. That paper came from the ledger books of soldiers and merchants, then became known as “ledger art.” Historical works were a continuation of narratives that had been painted on clothing, tipis, etc. As our people were forced onto reservations and into prison camps, the ledger paper was an available resource to visually record the way of life that had been decimated. I see my work as part of that continuum or our culture; as reinforcing our existence and reinforcing our contemporaneity.

“Atom Heart Mother (Earth),” mixed media on ledger, 16 x 10 inches, 2016

As a multimedia artist, how do you choose which materials to use in each piece?

A lot of the time, I am trying to utilize materials that would have been used historically in ledger art such as graphite, color pencils, or ink. I have also been influenced by other contemporary ledger artists who employ collages in their works. I often collage pieces of contemporary or vintage maps which act as a ledger of stolen lands.

What is the significance behind drawing on the Boy Scouts of America neckerchiefs?

These works are commenting on the problematic aspects of the Boy Scouts of America. I want to confront the systemic racism that is taught at an early age through the micro/macro-aggressions of mascots and misappropriation of imagery and culture of the Indigenous people of this land. The popular defense of racist mascots is that they “honor” us and mean no offense. However, a generalized depiction of a romantic ideal of what we were once supposed to be offers no honor and is clearly intended as a symbol of subjugation.

“Scout's Honor,” ballpoint pen on vintage Boy Scout neckerchiefs, approximately 100 x 20 inches, 2020

(continued) Through the medium of indelible ink, I am asserting our identity and our continued existence in the face of attempted erasure and negating the centuries of racist misrepresentations. The neckerchief as substrate alludes to the tradition of ledger art while also suggesting historical and contemporary manifestations of prison art; the context of which ledger art is sometimes associated. In the re-appropriation of an object that may have been considered sacred to some, I hope to impose a sense of what Native people feel when we’re confronted with sacred objects or the bones of our ancestors displayed as macabre entertainment or for capitalism.

I ask those that may find this work offensive to reflect upon their own experiences and question their complicity. This is not to place blame on the viewer but to act as an opportunity to recognize the roots of internalized racism and offer a chance for self-reflection. The ancestors portrayed are engaged in a dialogue with each other about their own ways of dealing with systemic and internalized racism. They are also engaging the audience about who and how a historical narrative is conveyed and who benefits from the alterations or distortions of those narratives. Truth and honor are virtuous to the idea of America and are not always easy to find in the history and institutions within.

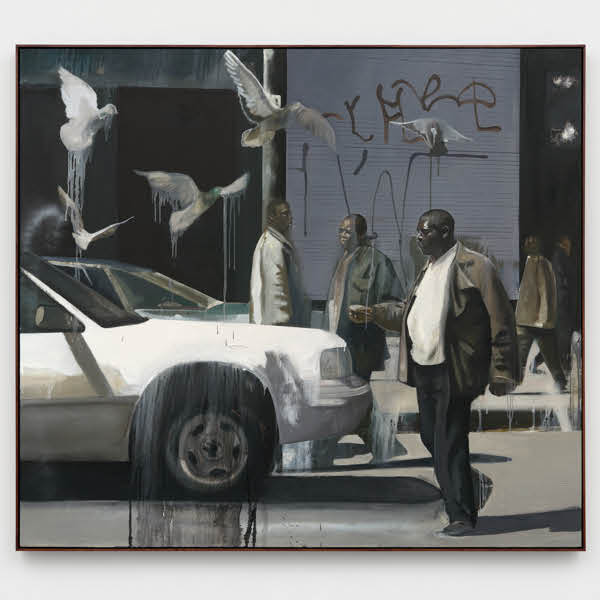

“Displaced Peoples,” acrylic and mixed media on wood panel, 40 x 30 inches, 2014

Your work invokes a lot of historical references. What kind of research do you do before starting a portrait?

I look at a lot of historical photographs and my drawings are based on those photos. What I find interesting is that a lot of those images were produced around the same time that ledger art was becoming a prominent cultural medium. Often the people or ancestors in the photos are misidentified so I will want to make sure I know who I’m drawing if possible. Usually, it takes asking people from those same communities to help identify them. Sometimes they’re not identified, but if they’re really interesting to me visually, I will move ahead in a respectful way.

The ledger paper substrate also has its own history and I try to get as much info on that as possible, such as the watermark, years used, purpose, etc. I am also trying to incorporate my people’s language into some titles of my work and that will get me looking through the Kanza language dictionary and attempting to translate ideas from English to Kanza.

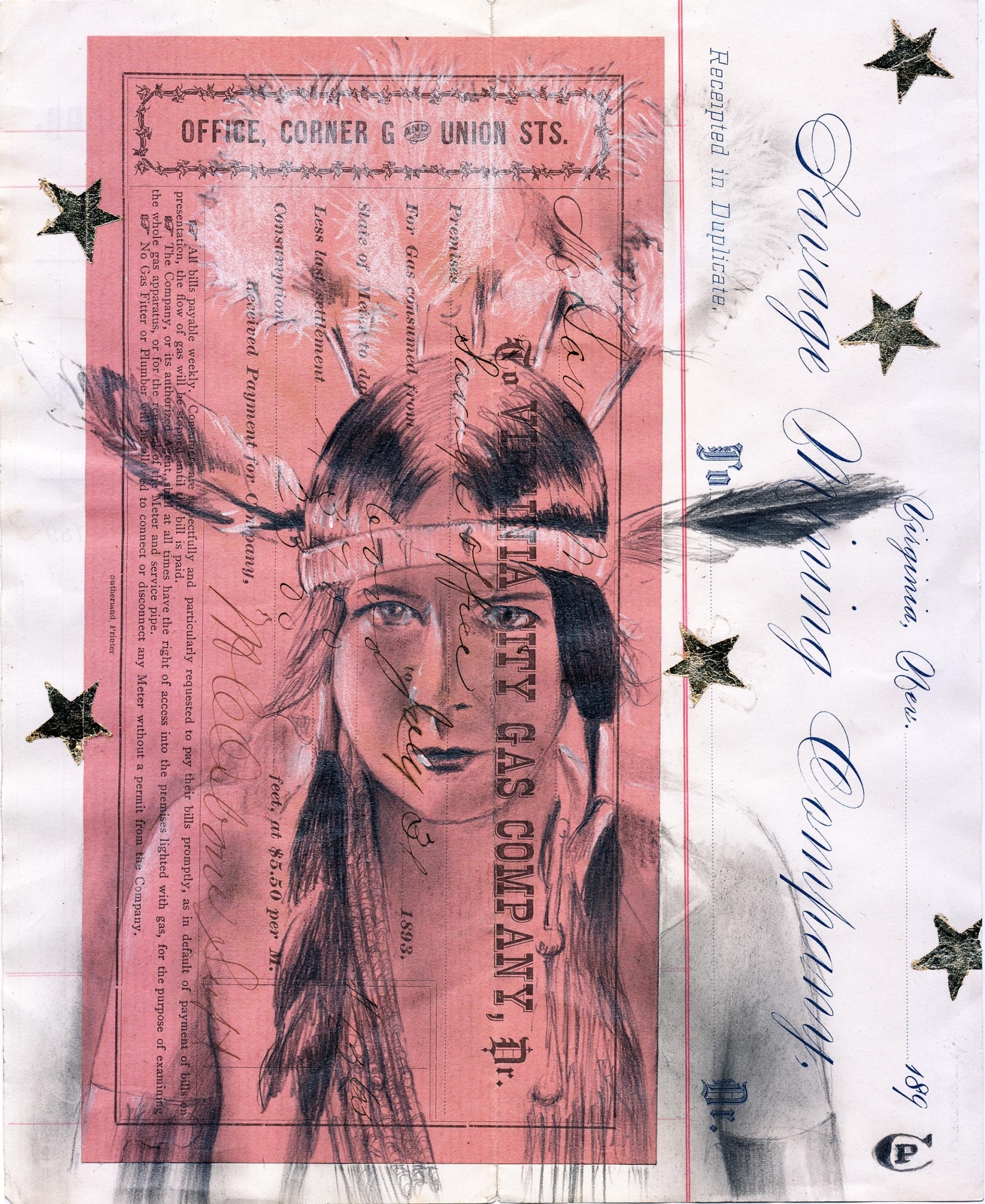

“La Sauvage,” mixed media on mining certificate, 9 x 7 inches, 2016

Can you elaborate on any of the figures that you’ve drawn?

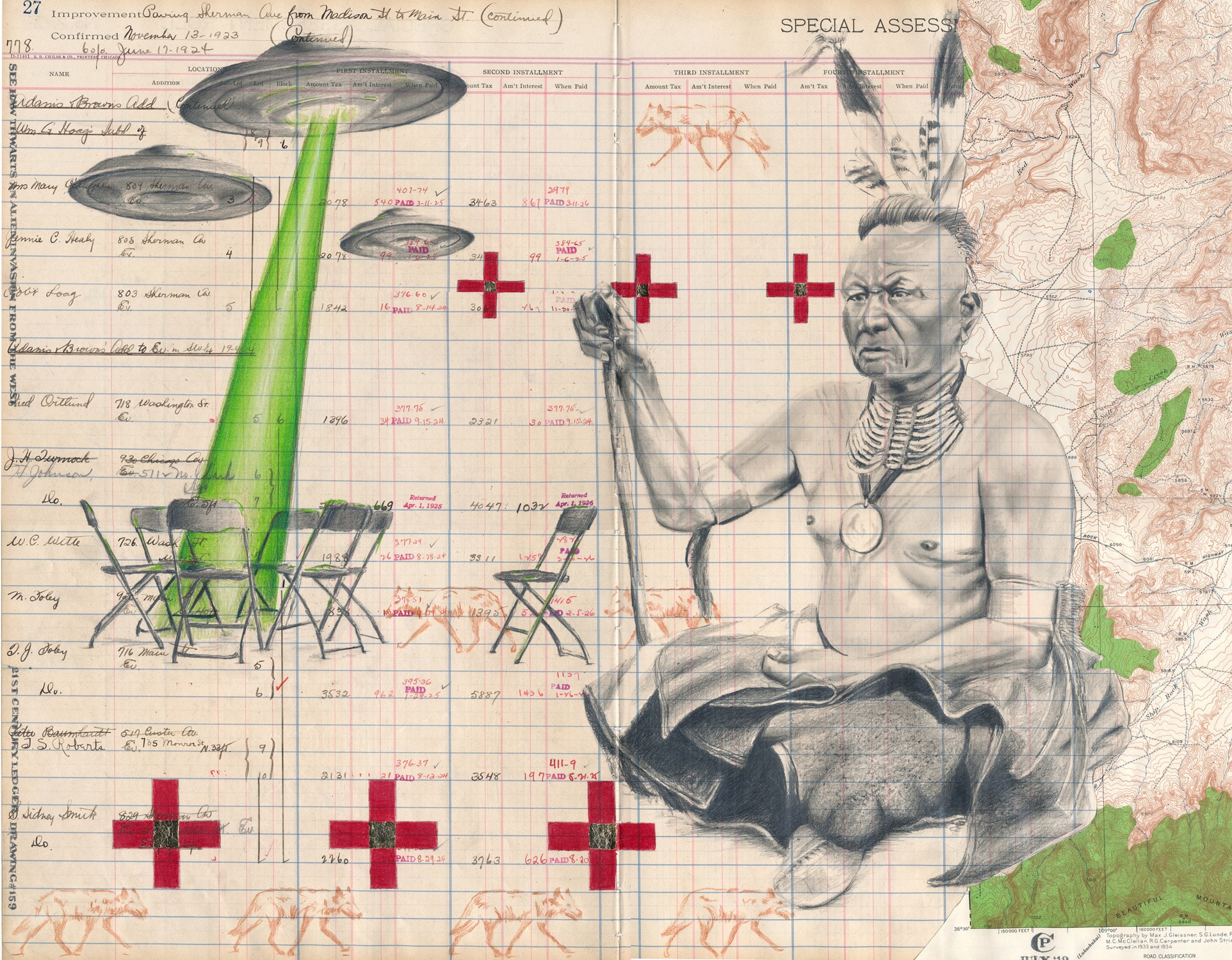

I have a couple of folks who keep recurring in work: See Haw (Osage), Bacon Rind (Osage), and Washunga (Kanza). Combing through old photos of Kanza people (my people) I came across a few images of this leader who just exuded brash confidence and a presence that transcends the boundaries of a mere photograph. After posting a few pieces I did of him on social media, I was contacted by his great-granddaughter who confirmed that he was in fact a real character! That ancestral connection and affirmation of humanity beyond the stoicism attributed to so many Native people really helped to crystalize the direction of my practice.

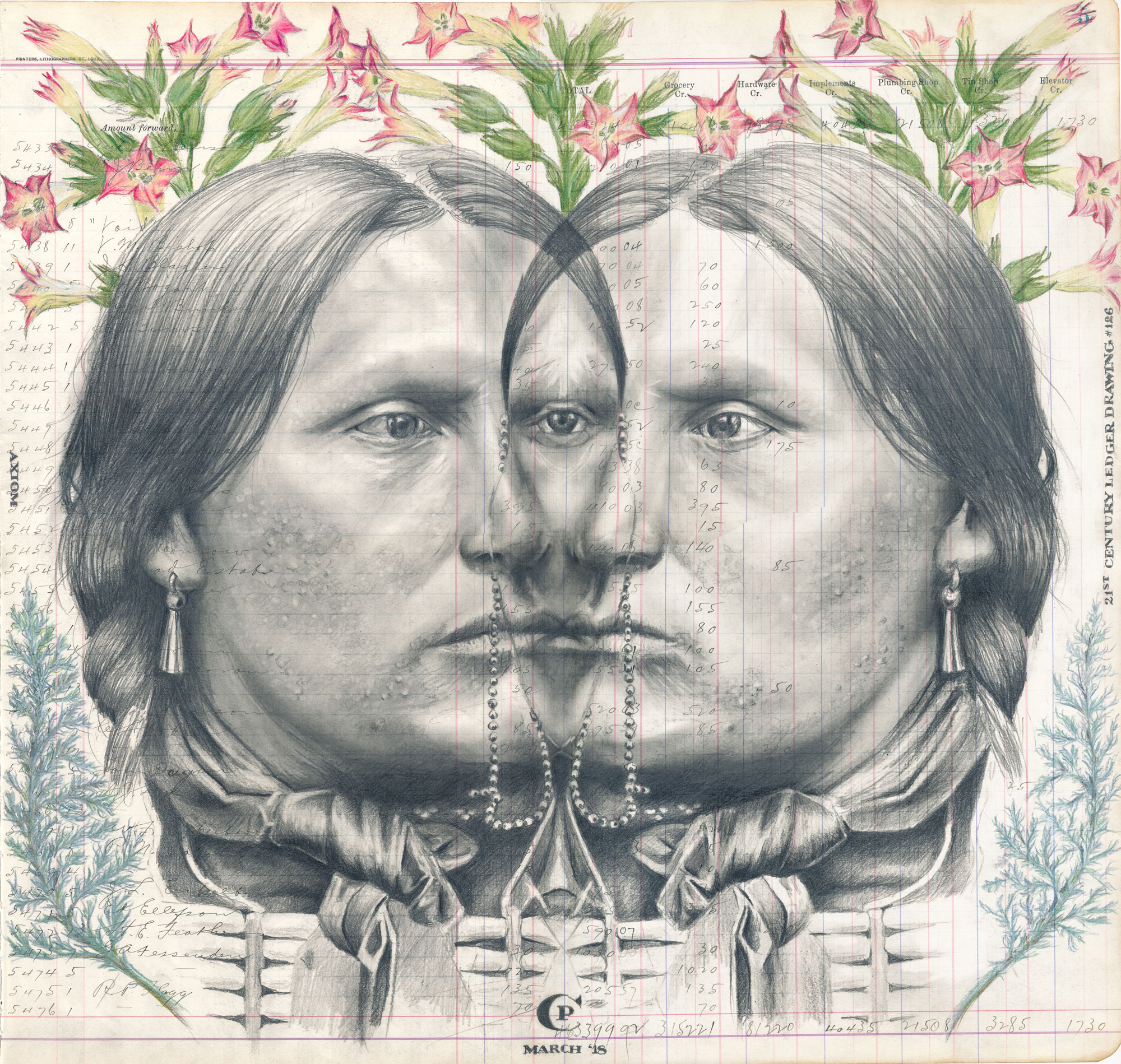

Is there a reason why you often choose to mirror the subjects in your portraits?

That started from a “happy accident” and I looked at it as a challenge to my drawing skills. But then it developed into a few different ideas: pulling oneself apart in order to assimilate; it could be taken literally as two sides to every story, but I see it more as a representation of two people or ideas coming together to create something new while paying close attention to the abstract forms that take shape within the confluence of the two figures. People will see that abstraction differently, bringing their own experience to the work.

“Axiom,” mixed media on ledger, 16 x 16 inches, 2016

How has your artistic practice changed over time (if it has)?

When I started my 21st Century Ledger Drawing series, I wanted to create a connection to the historic importance of the tradition while making it relevant today and for myself. I feel like I have been able to contribute to the tradition overall and helped to inspire other artists. Now, I try to think more about the narrative qualities of the tradition and how I can create contemporary narratives rather than trying to recreate events from the past. I want to relate my experience as a human being in this world.

Some of these works involve characters that relate to creation stories, deities that are prevalent in our world, helping us to cope with inequities but inspiring us to succeed. I am also interested in expanding the scale of my work. Ledger art tends to be confined to one page with very specific dimensions, and I am searching for ways to go beyond those borders and to expand the definition of the genre in the process.

“See Haw Thwarts and Alien Invasion from the West,” mixed media on Evanston municipal ledger, 18 x 23 inches, 2019

Are there any upcoming projects or exhibitions that you can tell us about?

I am a part of an exhibition called Two Man Show at Blue Rain Gallery in Santa Fe, which will be on display from February 26 to March 20, 2021.

I also just started an artist residency with the Chicago Public Library that will be addressing a WPA mural that depicts Native people and the “explorer” Marquette. Additionally, I have a project with the MacArthur Foundation and I'm going to be exhibiting more work at Art Expo Chicago this year (if it’s able to come together).

Chris Pappan: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Chris Pappan.

Related Articles:

Beautiful 50-Foot-Tall Sculpture Pays Tribute to Native American Women in South Dakota

Powerful Portraits of Native Americans Highlight Their Spirit and Cultural Identity [Interview]

Interview: Wet Plate Photographer Captures Powerful Portraits of Native Americans