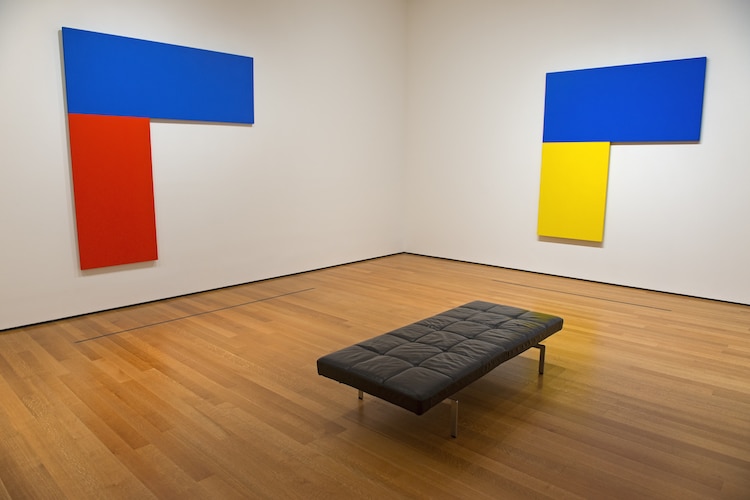

Ellsworth Kelly at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (Photo: Stock Photos from Jorn Pilon/Shutterstock)

Abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly is known for pushing the envelope with his avant-garde paintings, prints, and sculptures. Over the course of his stunning 70-year career, Kelly developed a distinctive approach to his practice, characterized by a preference for minimalism, a penchant for bold colors, and the “new freedom” of finding inspiration in the unexpected. “A glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched panes, lines of a roadmap, the shape of a scarf on a woman’s head, a fragment of Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion, a corner of a Braque painting, paper fragments in the street,” Kelly explained. “It was all the same: anything goes.”

While Kelly found inspiration in a wide range of subjects, there are certain motifs that had a particularly profound impact on his art. Here, we explore some of these important influences, from a childhood passion for birds to a cultivated interest in flora.

Explore the eclectic influences that shaped Ellsworth Kelly's avant-garde art.

Birds

In 1923, Ellsworth Kelly was born in Newburgh, New York. When he was a child, Kelly and his family relocated to Oradell, New Jersey, where he and his grandmother would birdwatch at a nearby reservoir. When paired with a passion for the work of artist and avid bird enthusiast John James Audubon, these excursions sparked a lifelong love of ornithology—a study that would play an unexpectedly important role in his artistic practice.

Kelly's most well-known works are highly abstracted. However, visual allusions to birds are often evident, from soaring shapes reminiscent of spread wings to specific color combinations inspired by plumage. “I remember vividly the first time I saw a Redstart, a small black bird with a few very bright red marks,” he explained in his monograph. Most of all, however, Kelly's interest in birds trained him to observe—and, ultimately, find inspiration in his surroundings. “I believe my early interest in nature taught me how to ‘see’.”

Camouflage

Ellsworth Kelly, “The Meschers,” 1951 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Fair Use])

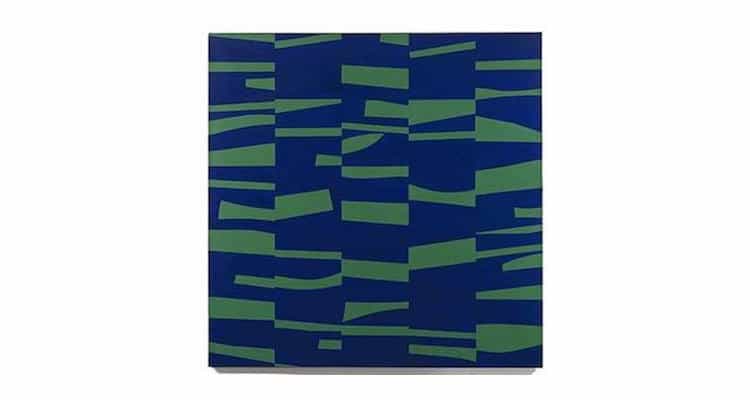

While each of these hands-on projects helped Kelly hone his artistic talents, his exposure to camouflage resonated particularly strongly. The aesthetic influence of this strategic use of tone and pattern is evident in several of his abstract works after 1949, including The Meschers and Colors for a Large Wall in 1951 and Méditerranée in 1952. Though these works comprise simple series of different-colored squares, their hidden reference to military camouflage reveals that—much like the muse itself—they're more than meets the eye. “My forms are geometric, but they don't interact in a geometric sense,” Kelly explained. “They're just forms that exist everywhere, even if you don't see them.”

Architecture

After the war, Kelly continued his formal education at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In 1947, however, he returned to France, enrolling at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts (National School of Fine Arts) in Paris. As a student in the French capital, Kelly had two important realizations: he was no longer interested in traditional, figurative painting; and inspiration was everywhere—especially in architecture.

“In October of 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, I noticed the large windows between the paintings interested me more than the art exhibited,” he recalled. “I made a drawing of the window and later in my studio I made what I considered my first object, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris.” Comprising a pair of canvases framed by strips of wood, this sculptural piece laid the groundwork for the experimental approach to art that would eventually define Kelly's career. “From then on, painting as I had known it was finished for me.”

Additionally, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris launched Kelly's interest in architecture, evident in everything from abstract gouache paintings of cityscapes to photographs of “buildings that rose to the sky from the dense Manhattan grid.”

Plants

Architecture was not the only muse Kelly cultivated while living in Paris. He also started looking to plant life for inspiration, culminating in a collection contour drawings of flowers, leaves, and seaweed.

Like Kelly's other sketches, his botanical drawings are rendered simply and quickly, serving predominantly as a study of the shape and color encountered in his surroundings. What sets them apart, however, is how he observes his subjects. “My ideas I can find anywhere,” he said. “And I draw because I have to note down my ideas or flashes—I call them flashes, because they come to me, like that. Not so much in the plant drawings. I have to see them.

While Kelly left France in 1954, he would continue exploring this theme for decades, whether crafting plant lithographs in Manhattan or sketching in Spencertown, where he moved in 1970 and remained until his death in 2015.

Related Articles:

7 Fascinating Facts About Alexander Calder

5 Intriguing Facts About Modern Master Willem de Kooning

6 Museums with World-Class Sculpture Gardens

6 Museums That Make San Francisco a Must-See City for Art and Culture