Photo: Stock Photos from PHANT/Shutterstock

The city of Rome is full of ancient buildings and modern churches—including some sites that are both. Among the most magnificent historical houses of worship is the Pantheon.

Built by the Romans likely as a temple or political space, the domed structure continues to fascinate engineers for its gravity-defying signature dome. The Pantheon is also a significant historical landmark that draws lines of continuity from polytheistic Rome through the Dark Ages to Renaissance opulence.

Whether you are seeking history or would like to attend mass in an ancient church, the beautiful Pantheon is a must-see on any visit to Rome.

Scroll on for nine fascinating facts about the history of Rome's ancient Pantheon church.

The exact date of origin of the Pantheon has confused scholars.

Left: Roman Emperor Hadrian (ruled 117-138 CE) (Photo: Livioandronico2013 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Right: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, military leader and son-in-law to Augustus. (Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5)

For a long time, the exact origins of the Pantheon confused scholars. It is now known the Pantheon was dedicated around 126 CE. However, the architect and exact dates of construction are unclear. The building bears a prominent inscription reading, “Marcus Agrippa the son of Lucius, three times consul, made this.” The text references Marcus Agrippa, a military leader who was son-in-law to the emperor Augustus (who ruled 27 BCE to 14 CE). Augustus and Agrippa both engaged in many building projects to transform Rome at the end of the Republican period.

Agrippa built his Pantheon on the site of the present-day building. The word pantheon derives from the Greek meaning “all gods.” This first Pantheon burnt down in 80 CE, and a second building likewise met its demise in 110 CE. (Fire was a frequent hazard in the ancient world.) Despite the confusing inscription, the present building actually dates to the reign of Hadrian. While the building may have been used as a temple, it also seems to have hosted certain political functions.

The Pantheon survived the Dark Ages—barely.

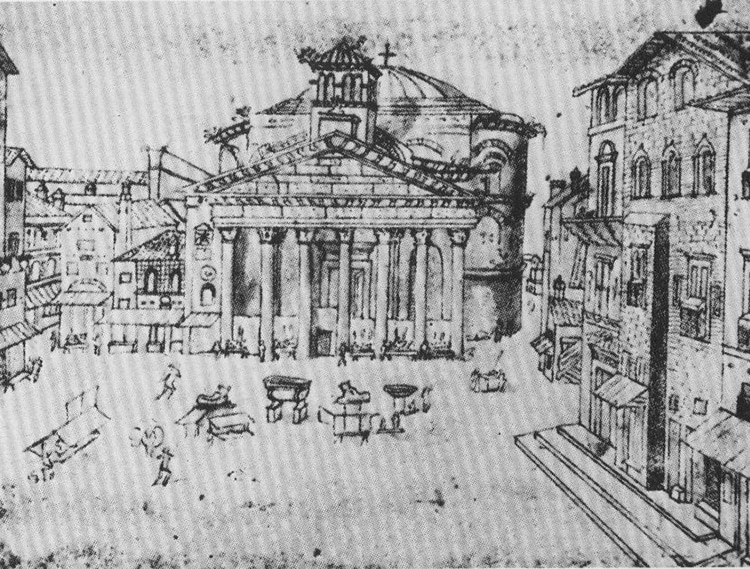

Sketch of the Pantheon in the 15th century, with only the single medieval bell tower. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The western half of the Roman Empire entered a long decline under external military pressures compounded by internal strife. In 476, the last true western emperor's rule ended. While the eastern half of the empire developed into the powerful Byzantine Empire, Italy in the west was under the rule of Germanic Ostrogoths until it was conquered by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great in the mid-6th century. Justinian established the Duchy of Rome within Byzantine-controlled Italy. For the next several centuries, Italy saw military conflicts and territorial divisions between the eastern Romans (also known as the Byzantines), the Lombards, and the Franks.

During this period often referred to as a “dark age” in Europe, the Byzantine Emperor Phocas allowed Pope Boniface IV in 609 to consecrate the Pantheon. The building became a Christian church known as Sancta Maria ad Martyres (St. Mary and the Martyrs), as the relics of many martyrs were transferred to be interred there. However, the building was not immune to the plundering and disintegration which plagued the ancient buildings of Rome. For example, in the late 7th century, Emperor Constans II stripped all the bronze from the church's dome to be melted down for imperial use. The original marble facing of the building was likewise often pillaged.

Several bell towers once existed.

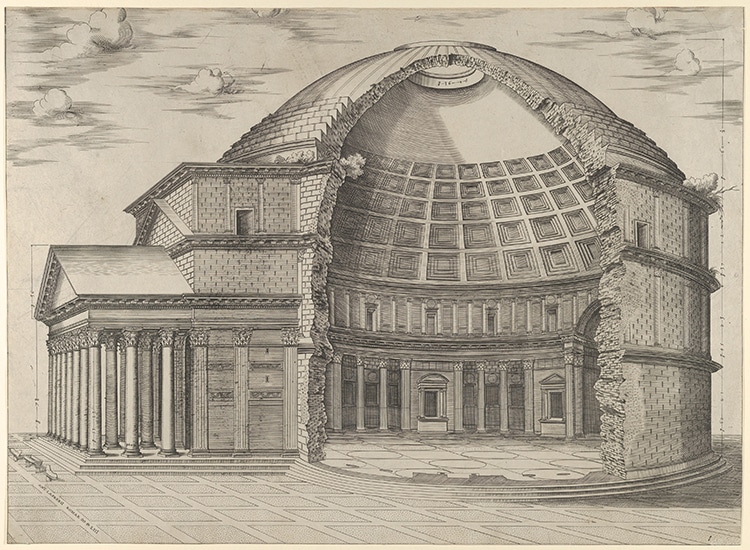

A reconstruction of the Pantheon (above) and the building around 1700 (below). Engraving by Jan Goeree, before 1704. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

In 1270, a central bell tower was added above the intermediate block connecting the portico to the dome. The 17th-century Pope Urban VIII removed the medieval addition to replace it with two new bell towers. These were apparently quite unpopular additions that the public mocked as donkey ears upon the classical facade. These two towers appear in artist's renderings from the period; however, sketch artists and painters also liked to portray the “reconstructed” Pantheon as they believe it looked in ancient days. The two bell towers would eventually be removed by Pius IX in the 19th century.

The pope once used the bronze decorations to make canons.

Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Pope Urban VIII did more to the Pantheon than just adding the twin bell towers. The Pope stripped the bronze decorations from the portico in 1626. These were melted and used to create 80 canons for the Castel Sant'Angelo. The Castel Sant'Angelo is another classical building, dating from the 2nd century. Originally a tomb for Emperor Hadrian, the building was repurposed by the papacy as a papal residence and fortress; the bronze cannons were only part of the building's impressive defensive capabilities.

The design of the Pantheon was groundbreaking and set the tone for buildings to come.

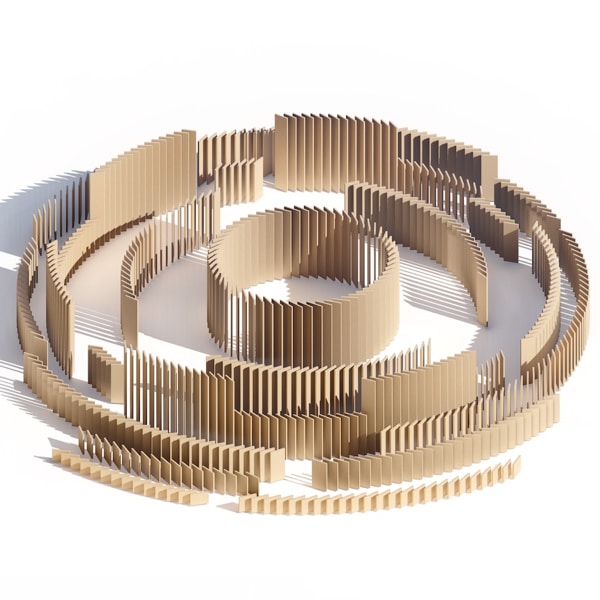

A cut-away view of the Pantheon, by an anonymous artist in 1553. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

While today many people regard the Pantheon as representative of Roman architecture, the building was unique at the time of its construction. The combination of a domed temple cella (inner room) with a classic portico (columned porch) and traditional triangular pediment (the front-piece of the portico) was relatively rare—especially for such a large-sized structure. The enormous dome is crafted from concrete and supported by the lower walls of the rotunda which are up to six meters thick.

Featuring a coffered design, the dome is a marvel of ancient engineering. It is the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world, including no steel supports as such structures would today. Measuring about 143 feet in both diameter and height, the structure would perfectly contain a 143-feet-in-diameter sphere.

The Pantheon dome is famous for its central feature—an opening of roughly 20 feet in diameter. Known as an oculus, this hole serves an important architectural purpose by properly distributing the force of the large dome. As it is open to the elements, the floor was specially crafted in convex marble to channel rainwater to drains. The circular patterns of the Pantheon—as seen in the oculus, dome, and the decoration of the lower rotunda—inspired many later buildings, including Thomas Jefferson's designs at the University of Virginia and the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

Renaissance artist Raphael is buried in the Pantheon.

Left: The grave of Raphael and Maria Bibbiena. (Photo: Ricardo André Frantz via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Right: Self-portrait by Raphael, circa 1504-1506. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Renaissance painter Raphael (full name Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) is perhaps best known for his fresco The School of Athens in the Vatican. The brilliant young artist passed away at 37 in 1520. A darling of the ecclesiastical art patrons, he was interred with great ceremony in the Pantheon. He shares his tomb with his fiancée Maria Bibbiena.

The Pantheon is still an active Catholic church.

The altar in the Pantheon. (Photo: Bengt Nyman via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

While it is a monument of world heritage, the Pantheon today is still an active church. It is a Catholic Basilica and mass is celebrated on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. On Pentecost, for example, red rose petals are strewn from on high within the church's rotunda. Midnight mass at the Pantheon is a sight not to miss if you happen to be in Rome for the holiday season.

The Piazza della Rotonda, on which the Pantheon sits, features an Egyptian obelisk.

Piazza della Rotonda, seen with the Pantheon and obelisk. By Giovanni Battista Piranesi, circa 1751. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The Pantheon has long sat on an open square known as the Piazza della Rotonda. In the 15th century, Pope Eugenius IV cleared the clustered medieval buildings in front of the church to create a paved plaza. In the 16th century, a central stone fountain was added. And in the early 18th century, an Egyptian obelisk was also erected in the center of the redesigned fountain (created by Filippo Barigioni). The ancient red marble obelisk was brought to Rome in antiquity and rediscovered in the medieval period. All over Rome, ancient materials were often reused in medieval and early modern building projects.

The Pantheon features in Dan Brown's popular The Da Vinci Code.

Photo: Stock Photos from HERACLES KRITIKOS/Shutterstock

Even if you have never visited Rome, you may be familiar with the Pantheon through Dan Brown's bestselling book Angels & Demons. Although the book and its series are not free from factual errors, they enchanted readers across the world with the possibility of mystery and magic in historic Rome. The book and its predecessor The DaVinci Code inspired a whole new audience to take an interest in history and incredible monuments to time and human achievement such as Pantheon.

Related Articles:

11 Architectural Styles That Define Western Society

5 Art Deco Buildings That Embody the Vintage Glamour of This Architectural Style

All Aboard for the History of the Grand Central Terminal, an Iconic NYC Landmark

10 Incredible Mosques of the World Celebrating the Grandeur of Islamic Architecture