“Apocalypse Tapestry” (detail) (Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the oldest forms of textile art, tapestry weaving was a prominent craft from the second half of the 14th century to the end of the 18th century. In Europe, the period saw the production of large wall tapestries that were typically owned by royals and the elite. Kings, queens, and aristocrats often used them to decorate both indoor and public spaces to display their wealth. Henry VIII, for example, had around 2,000 tapestries hanging in his various palaces.

A tapestry is created by weaving colored weft threads through plain warp threads. Using wool or silk, the weaver builds up blocks of color in a specific order to create patterns and images. The complex technique allows the maker to create tapestries that illustrate colorful scenes. Many famous tapestries from history retold stories from the Bible and mythology, while others depicted scenes from significant, real-life events.

Read on to discover five tapestries from history that contain fascinating tales, rendered in thread.

Unravel the intricate stories behind these five famous tapestries.

Apocalypse Tapestry

The “Apocalypse Tapestry” 1377-1382 (Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Apocalypse Tapestry was woven in Paris between 1377 and 1382. It was commissioned by Louis I, the Duke of Anjou, and depicts the story of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation by Saint John the Divine. The 140 meters long, six-meter-high tapestry features around 90 scenes woven in colorful thread spread over six panels. A Flemish artist named Jean Bondol came up with the designs that were later interpreted by craftspeople as large, textile weaves.

Although the theme of the apocalypse is somewhat bleak, the tapestry actually displays a positive message. During the 14th century, the apocalypse was a popular story and focused on the heroic aspects of the last confrontation between angels and beasts. Many of the scenes in the Apocalypse Tapestry depict destruction and death, but the design ends with a joyful story of good conquering evil.

It is unclear how Louis I displayed the tapestry, but some historians believe it was exhibited publicly, outdoors. The Apocalypse Tapestry now sits in the castle Château d’Angers in west-central France.

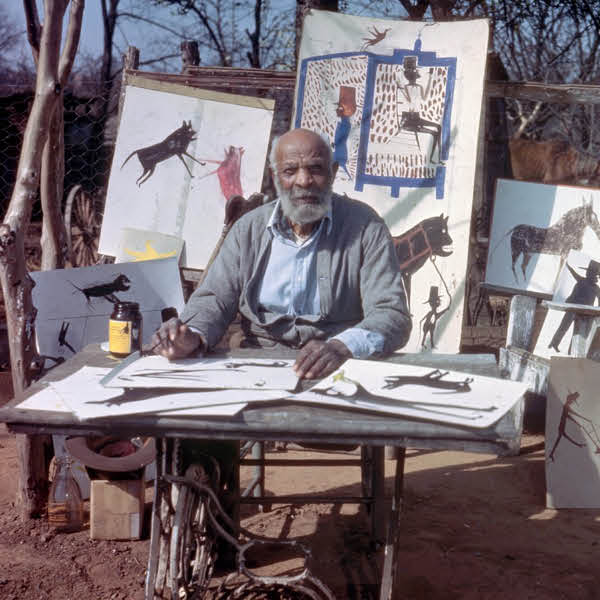

Hunt of the Unicorn

“The Unicorn Defending Himself” from the “Unicorn Tapestries” series, 1495–1505 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Hunt of the Unicorn (also known as the Unicorn Tapestries) is a series of seven tapestries made in Paris during the 16th century. Woven from natural-dyed wool, metallic thread, and silk, the tapestries feature a variety of bright hues and beautiful details.

The elaborate textile design depicts a group of high-born men hunting a unicorn, set in an idealized French landscape. Each tapestry illustrates a different moment from the pursuit, from “The Start of the Hunt” to “The Unicorn in Captivity.” There are several theories about the symbolism of the series, but some Christian scholars believe the unicorn represents Christ and the hunt represents his crucifixion.

The Unicorn Tapestries are currently housed in The Met Cloisters Museum in New York.

Lady and the Unicorn

“The Lady and the Unicorn” 1484-1500 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The mystical unicorn was a common motif in historic tapestries, but unlike the previous Hunt of the Unicorn series, this six-part collection has a more peaceful narrative.

The Lady and the Unicorn series was designed in Paris and woven in Flanders around 1500. Woven from wool and silk in the style of mille-fleurs (meaning “thousand flowers”), the series is often considered one of the greatest European works of art of the Middle Ages.

Each of the six designs features a noblewoman with the unicorn on her left and a lion on her right (some also include a monkey in the scene). It is commonly accepted that five of the tapestries represent the five senses—touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight—while the sixth represents love or desire. In Touch, the lady’s hand touches the unicorn’s horn; in Taste, a monkey is eating a sweetmeat; in Smell, the monkey is sniffing a flower; in Hearing, the animals listen to music; and in Sight, the unicorn is looking at itself in a mirror. In the final tapestry, the woman places down (or picks up) a necklace into a box, which is believed by some to represent desire.

Fun fact: All six tapestries covered the walls in the Gryffindor Common Room in the Harry Potter film series. The set is now on display in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

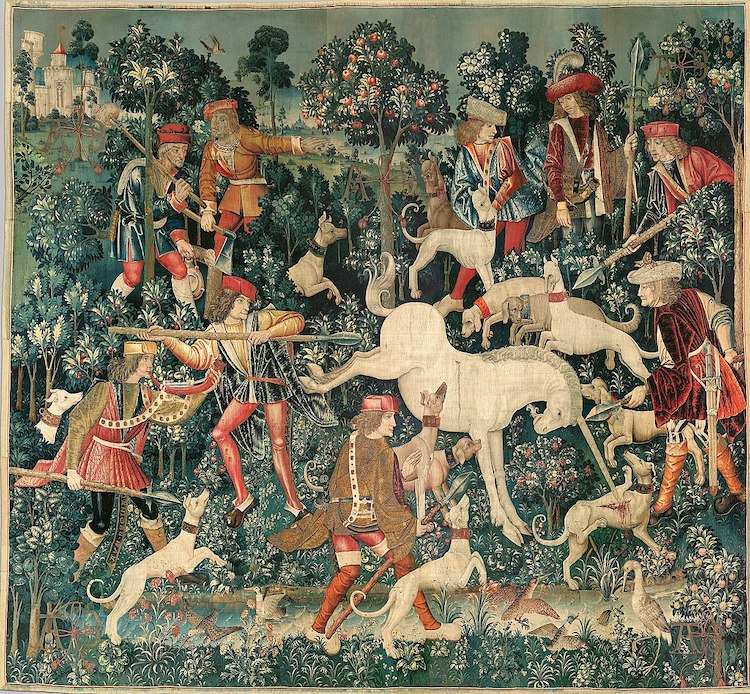

Bayeux Tapestry

“Bayeux Tapestry” (detail), c. 1051-1099 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Although it’s called the Bayeux Tapestry, this iconic piece of textile art wasn’t woven (like traditional tapestries)—it was embroidered. Measuring 231 feet (70 meters) long and 19.5 inches (49.5 centimeters) wide, it presents a rich representation of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 with 58 different scenes.

It begins with the journey to Normandy in 1064. King Edward the Confessor is talking with Harold, Earl of Wessex, who then departs for his family estate in Sussex with his hunting dogs. Although the end panel of the embroidery is missing and still a mystery, the existing end of the cloth shows the Anglo-Saxons fleeing at the end of the Battle of Hastings in October 1066.

The Bayeux Tapestry was likely commissioned by Odon de Conteville, Bishop of Bayeux and half-brother of William,

to decorate the new cathedral of Bayeux in the 11th century. However, today it still provides a fascinating and accurate depiction of the Middle Ages. In addition to presenting visual information about military items (such as weapons and armor), it also gives details of everyday life during the time. Luckily, the piece survived both the French Revolution and the Nazi occupation of France. It now stays at the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy.

Devonshire Hunting Tapestries; Swan and Otter Hunt

“The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries; Swan and Otter Hunt” 1430-1450 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries are a group of four very large tapestries made between 1430 and 1450 in Arras in Artois, France. Each one measures around 9 feet wide (3 meters) and depicts early 15th-century men and women in elaborate court dress hunting forest animals such as boars, bears, swans, otters, deer, and falconry.

The almost 600-year-old works are the only great 15th-century hunting tapestries to survive. They belonged to the Devonshire family and were displayed in their Chatsworth House in England for more than 500 years before they were allocated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. However, it was recently announced that two of the tapestries are returning to Chatsworth House. The current Duke of Devonshire said it was “a great privilege” to have them back.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Free Online App Lets You Create Your Own Bayeux Tapestry

Artist Spends 520 Hours Reimagining World Map as a Giant 20-Foot-Wide Tapestry

30-Foot Hand-Stitched Tapestry Tells the Story of Star Wars

Learn to Love the Loom When You Try the Ancient Art of Weaving