Handmade Halaf pottery bowl with seven‑petalled rosettes from Tell Arpachiyah, Iraq, Halaf period (6000–5000 BCE). (Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY‑SA 4.0)

Long before numbers were written down or equations were formalized, human beings were already thinking mathematically; not on tablets or scrolls, but in clay. New research into some of the world’s oldest known floral pottery, conducted by team from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, suggests that what was once seen as a simple decoration may actually be one of the earliest expressions of mathematical thought, quietly embedded in art from more than 8,000 years ago.

These vessels were made by the Halaf culture, a Neolithic society in northern Mesopotamia that flourished between approximately 6200 and 5500 BCE. Halafian potters decorated bowls and plates with finely painted floral and vegetal motifs that wrap rhythmically around curved surfaces. At first glance, these designs appear ornamental, but closer analysis reveals an underlying order.

The authors of the research, Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich, who studied hundreds of pottery fragments, found that many of the floral patterns follow repeating numerical sequences. Petals and leaves are arranged in groups that double in number, forming progressions such as four, eight, 16, and 32. Creating these designs required dividing circular surfaces into equal segments and distributing motifs with precision, suggesting a sophisticated understanding of symmetry, proportion, and spatial planning.

What makes this discovery striking is that it predates written mathematics by thousands of years. Without numbers or diagrams, early potters translated abstract concepts into visual form. Their understanding of geometry was not theoretical but tactile, learned through observation and repeated practice.

Rather than focusing on animals or human figures, Halafian artists abstracted flowers and leaves into systematic, structured forms. Nature became a framework for pattern, where organic shapes were transformed into systems of repetition and balance.

These ancient ceramics suggest that mathematical thinking did not suddenly emerge with writing, but grew gradually through creative practice. Embedded in clay and pigment, the floral patterns showed how early humans used art to organize the world around them, allowing mathematics to quietly take root long before it had a name.

According to new research, it appears that the world’s oldest floral pottery have patterns that are more than aesthetic designs — they are prehistoric mathematical thinking.

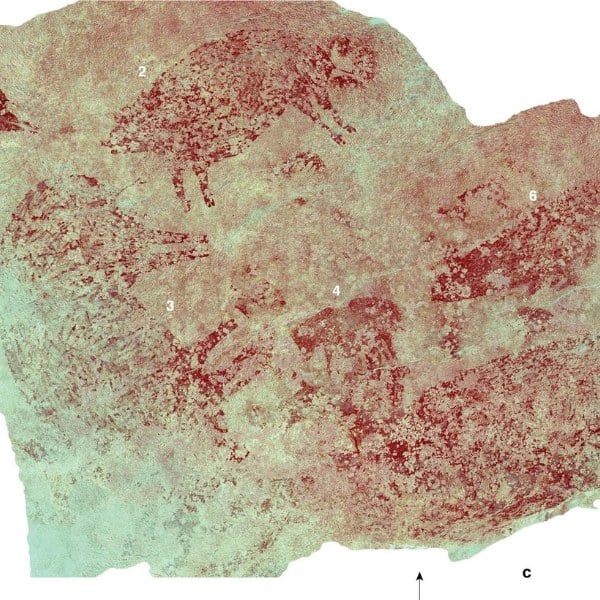

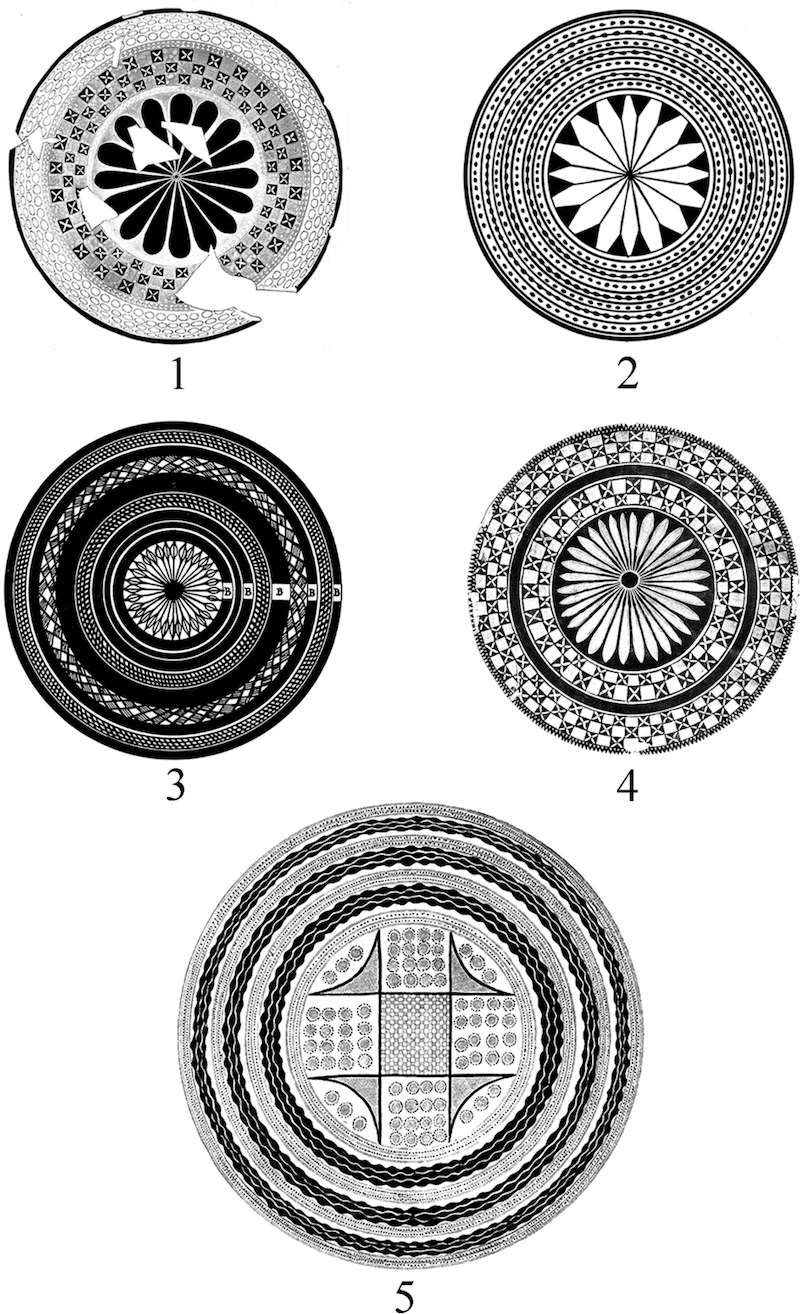

A drawing of Halaf floral motifs showing symmetrical large flowers with 16, 32, and 64 petals and arrangements on pottery from Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra (Halaf period, 6200–5500 BCE). Image adapted from The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art: Painted Halafian Pottery of Mesopotamia and Prehistoric Mathematical Thinking, Journal of World Prehistory. (Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY‑SA 4.0)

From petals to patterns, Halaf pottery reveals a surprising connection between prehistoric creativity and early mathematical thinking.

A drawing of Halaf floral motifs showing symmetrical large flowers with 16, 32, and 64 petals and arrangements on pottery from Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra (Halaf period, 6200–5500 BCE). Image adapted from The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art: Painted Halafian Pottery of Mesopotamia and Prehistoric Mathematical Thinking, Journal of World Prehistory.

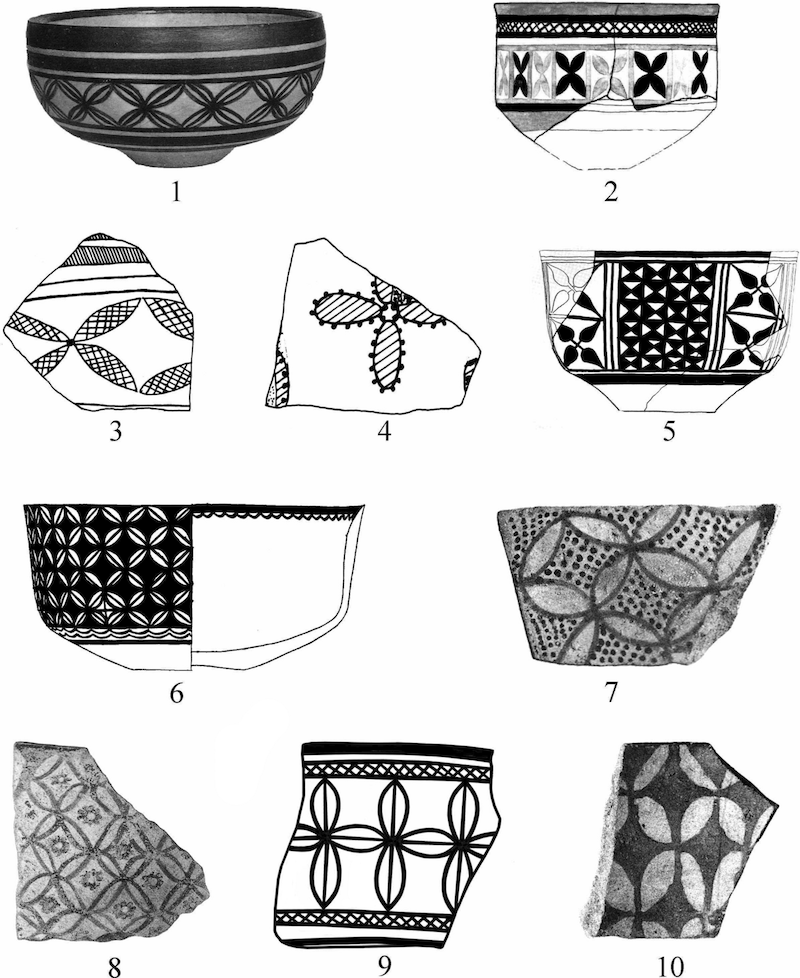

Various compositions of small four‑petalled floral motifs on Halafian painted pottery from Tell Halaf, Chagar Bazar, Ugarit, and Arpachiyah (Halaf period, 6200–5500 BCE). Image adapted from The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art, Journal of World Prehistory.

These delicate floral motifs were more than decoration—they are evidence of geometry and abstract reasoning in prehistoric art.

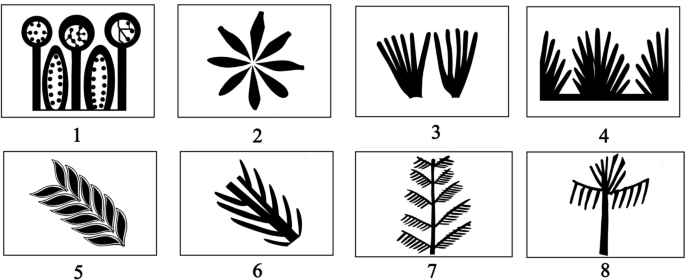

Classification of Halafian vegetal motifs into four basic categories—flowers, shrubs, branches, and trees—on painted pottery (Halaf period, 6200–5500 BC). Image adapted from The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art, Journal of World Prehistory.

Sources: Ancient Math Hidden in Oldest Known Floral Pottery; The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art: Painted Halafian Pottery of Mesopotamia and Prehistoric Mathematical Thinking

All images via Yosef Garfinkel & Sarah Krulwich except where noted.

Related Articles:

Tracing the History of Decorative Art, a Genre Where “Form Meets Function”

Archeologists Uncover Neolithic Stone Tomb With Hugging Skeletons in Scotland

Learn About the Fascinating History of Polish Bolesławiec Pottery

Uncover the History of Ancient Greek Pottery and How It Evolved Over Centuries