“The Dance Class” by Edgar Degas, 1875, Musée d'Orsay. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

As the style spread across 16th-century Europe, the dance developed into an art form which was eventually professionalized and perfected. Read on to learn about the origins of ballet—a graceful yet powerful discipline which has captured the hearts of children and catapulted talented dancers to stage stardom.

“Stage Setting with Ballet” by Ferdinando Galli Bibiena (Italian),

1657–1743. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art [Public domain])

Le Ballet de Cour

The earliest ballet dances were part of highly ritualized court entertainment in Renaissance Italy. The performances were choreographed routines performed by aristocrats—men and women—in their elaborate courtly dress. These dances were common at elite weddings where audience members would join in on the fun. Early dances featured mythology and political symbolism.

The term ballet, however, comes from the French ballet de cour, a stylized performance of dance, theater, and speeches. The first ballet de cour took place in 1573 at the French court—encouraged by the Italian-born Queen of France Catherine de' Medici who imported her love for ballet. The first performance featured female dancers representing the French provinces.

Louis IV as Apolo the Sun King in “Ballet de la Nuit,” by Henry de Gissey, 1653. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

18th-Century Innovations

“Pas De Deux” Figurine of two Ballet Dancers, Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory, c. 1760-63. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art [Public domain])

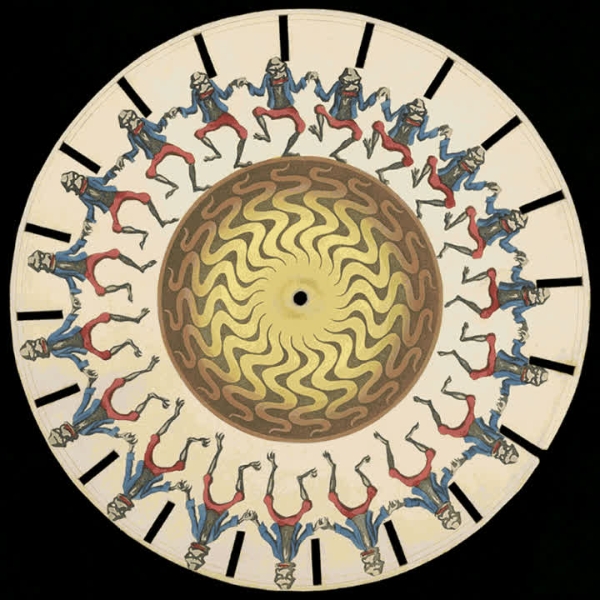

The most important figure of 18th-century ballet was Jean-Georges Noverre, who is typically credited with the narrative shift to the storytelling ballet d’action. The French dancer and choreographer wrote Lettres sur la Danse et les Ballets. Published in 1760, the text outlines a style of ballet based on the relationships of characters. This new style drew on the ancient art of pantomimes, and the ballet d’action was also known as a pantomime ballet. Noverre's most famous ballet—Les Fêtes Chinoises—fully embraced the Rococo aesthetic. A trained corps de ballet performed in front of luxurious set designs. The Parisian public loudly praised the ballet upon its first performance in the city in 1754.

Staged in theaters and opera houses, ballet was becoming more available to audiences outside of the royal court. The art remained dominated by male choreographers, but women did compose and appear on stage as well. Marie Sallé—an early inspiration to her student Noverre—was one such woman. Known as one of the earliest dancers to embrace a truly emotive style, she performed at the Paris Opera and Covent Garden before retiring to teach dance. Her skills were so revered, she was still sought out by nobility in her retirement—she even performed at Versailles. In addition to her dancing, she choreographed her own ballets—including one called Pygmalion, based on the Greek myth of a man who sculpts a female companion.

Romantic Ballet

Ballerina Marie Taglioni in “Zephire et Flore,” c. 1831. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

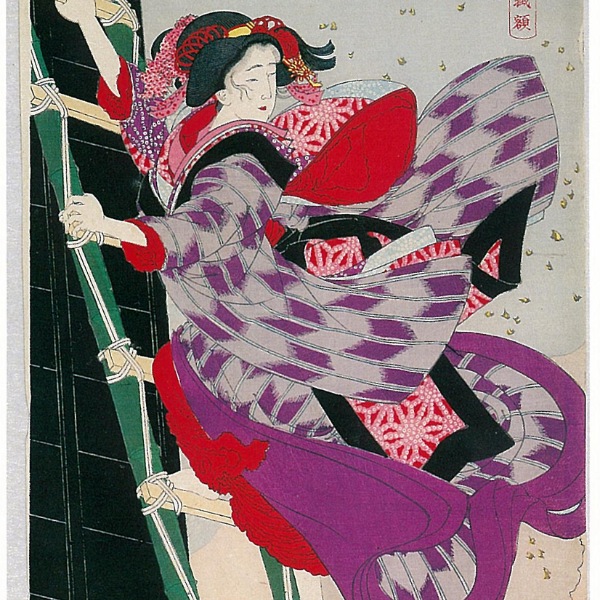

The Romanticism which pervaded European art in the 19th century also affected ballet. Many works of classical ballet were written during this period and are known as romantic ballets. Among these are La Sylphide (1836) and Giselle (1841). Both are still performed today, although often with newer choreography. Soft movements, folk characters, and countryside settings were characteristic of the new genre. Ballerinas wore long tulle tutus and specially made point shoes to dance their leading roles.

Although ballet originally arrived in Russia under the westernizing campaigns of Peter the Great, the pinnacle of Russian ballet is commonly thought to have begun in the late-19th century with the arrival of the French choreographer Marius Petipa. Residing in Russia, he created the renowned ballets The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and The Nutcracker (the latter two in collaboration with Lev Ivanov). These ballets—still some of the most frequently performed today—helped establish Russian preeminence in the world of classical dance. By the late 19th century, ballet performances could be seen by people across a range of social classes around the world in theaters and music halls. While not all dancers earned positions in major companies, those who did were revered and could even be household names.

Modern Companies and Neo-Classical Choreographers

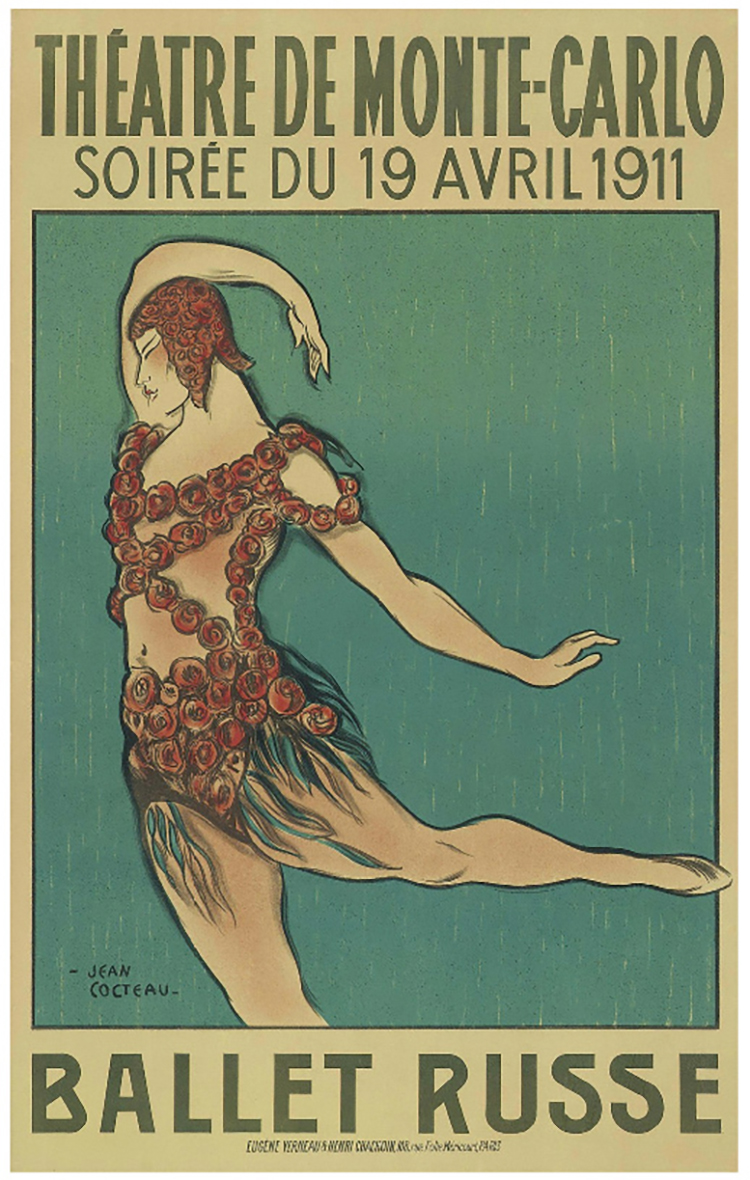

Poster for the traveling Ballet Russes corp de ballet. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

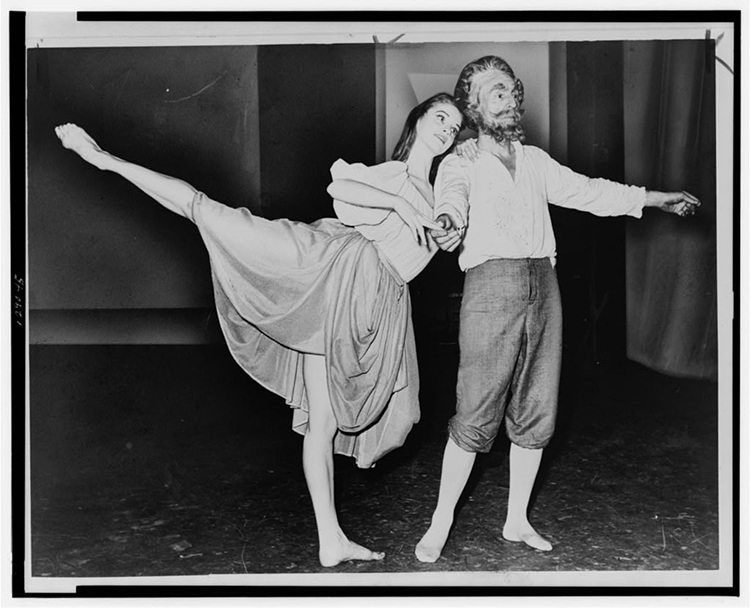

Suzanne Farrell and George Balanchine, performing “Don Quixote” in New York, 1965. (Photo: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection/Library of Congress)

The latter half of the 20th century brought a new style known as neoclassical ballet. A young Russian dancer who trained at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg, George Balanchine became one of the most important figures in modern ballet. The young, classically trained dancer fled Soviet Russia in 1924 and joined the Ballets Russes in Paris as their choreographer. In Paris in 1928, his work Apollo debuted, and is considered today to be the first neoclassical ballet. Its pared-down aesthetic and choreography driven by the music (rather than the story) was innovative.

In 1933, Balanchine moved to the United States. He founded the School of American Ballet in 1934 and the New York City Ballet in 1948. The modern American ballet tradition has been heavily influenced by Balanchine and his modern, avant-garde choreography which appreciated the formerly neglected male dancers. Legendary male dancers of the mid-century period are still revered today, such as Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov. The latter danced with Balanchine's New York City Ballet briefly out of a desire to study with the renowned choreographer, but Baryshnikov is primarily known for his decades of work with the American Ballet Theatre as a dancer and artistic director.

Contemporary Ballet

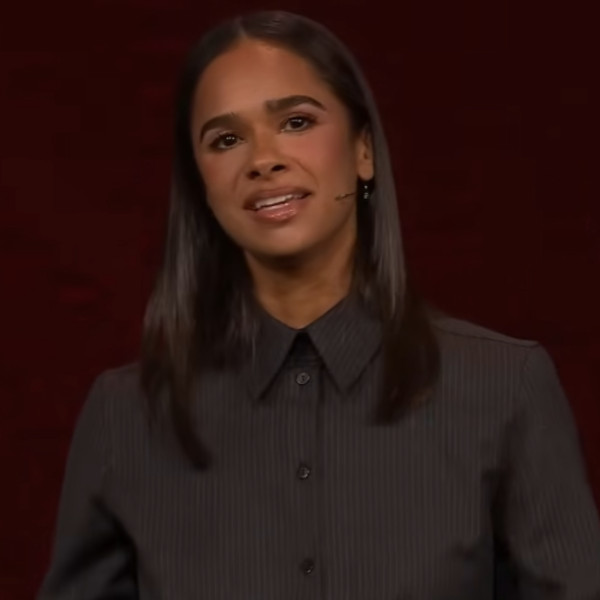

Today, many classical ballets are still tremendous crowd pleasers; roles such as the Sugarplum Fairy and Giselle can make a dancer's career. However, contemporary ballet goes beyond the work of the 19th-century choreographers. Building upon the narrative-less, emotional compositions of Balanchine and other neoclassical artists, contemporary ballet pushes limits. Costumes can be minimal, ballet slippers missing, or sophisticated special effects synced with dancers' movements.

Misty Copeland dancing in “Coppélia,” 2014. (Photo: Naim Chidiac Abu Dhabi Festival via Gilda Squire and Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 ])

To watch a demonstration of 400 years worth of development in ballet done in seven minutes, check out this video from the Royal Opera House.

Related Articles:

Breathtaking Portraits Capture Ballet’s Finest Dancing on the Streets of New York

Watch Ballet Dancers Move Through the Streets of Harlem in Breathtaking Performance

Stunning Drone Photos Capture Unique Perspective of Ballet From Above

25 Creative Gifts for Dancers That Celebrate the Art of Movement