Photo: Daniel Chodowiecki (Public domain)

There are some inventions that have changed the course of human history, and the printing press is one of them. As the name suggests, this machine allows for the mass production of printed matter like newspapers and books. Its function sounds unremarkable today, but when the printing press was refined by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, it was nothing short of revolutionary.

Learn more about the printing press history and how this invention shaped the culture and laid the groundwork for the world we know today.

Photo: Stock Photos from marekuliasz/Shutterstock

China and the Printing Press Machine

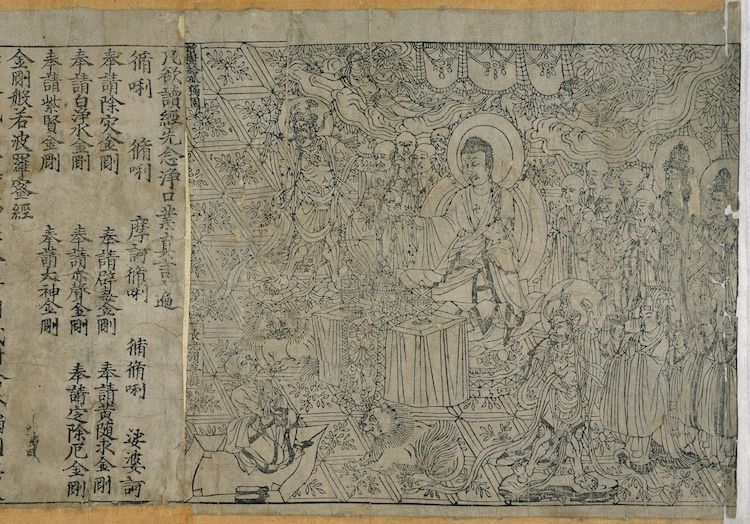

Photo: A page from Diamond Sutra (Public domain)

The Diamond Sutra

The most common iteration of the printing press is the Gutenberg press—but it wasn’t the first. It’s unknown who invented the initial printing press, but the oldest known printed text came from China. Called The Diamond Sutra, it’s a Buddhist scroll that was published around 868 CE.

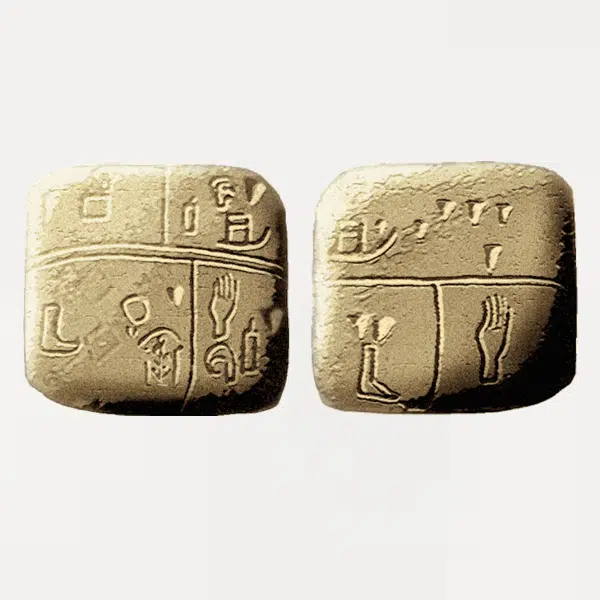

While this printed text marked the reproduction of text (that wasn’t done by hand), the type of printing it used was block printing, which involves hand-carved woodblocks cut in reverse. The blocks were cut specifically for a project, and they couldn’t be reused for another one.

Bi Sheng and Moveable Type

Moveable letters, also called moveable type, was developed by Bi Sheng in China shortly into the second millennium. He carved individual letterforms into clay and baked them into hard blocks. When inked, they were pressed against paper. Although it was easier to produce than the block printing method, the process was expensive—making mass printing reserved for the upper class.

Wang Chen and the World’s First Mass-Produced Book

Although wooden typography had a reputation for absorbing too much ink and not being made to last, it reemerged in 1297 thanks to Wang Chen and his publication on agriculture and farming called Nung Shu.

Chen improved on wooden text by developing a process that made the blocks more durable. He also made it easier for typesetters (the people placing the blocks) to do so in an efficient manner. These advancements made Nung Shu the first mass-produced book that the world had ever seen.

Korea and Movable Metal Type Printing

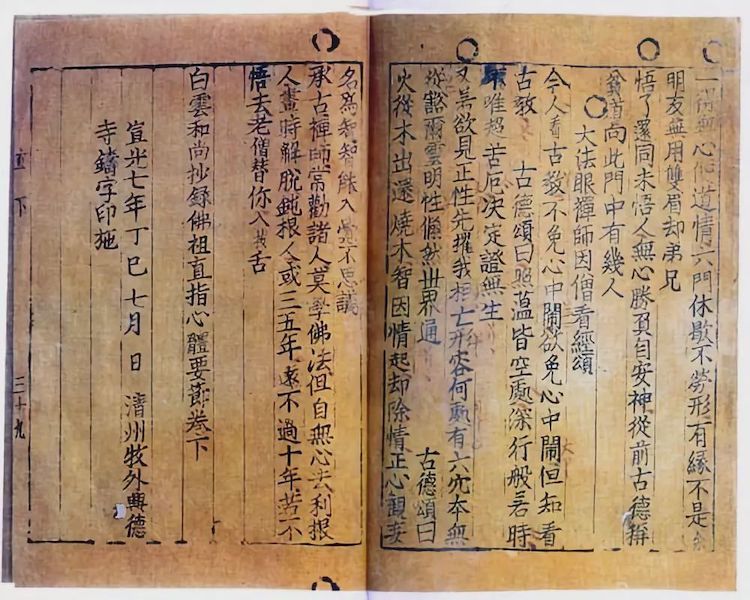

Jikji – the earliest known book printed with movable metal type, 1377. (Photo: Bibliotheque Nationale de France [Public domain])

Johannes Gutenberg and Printing Press History

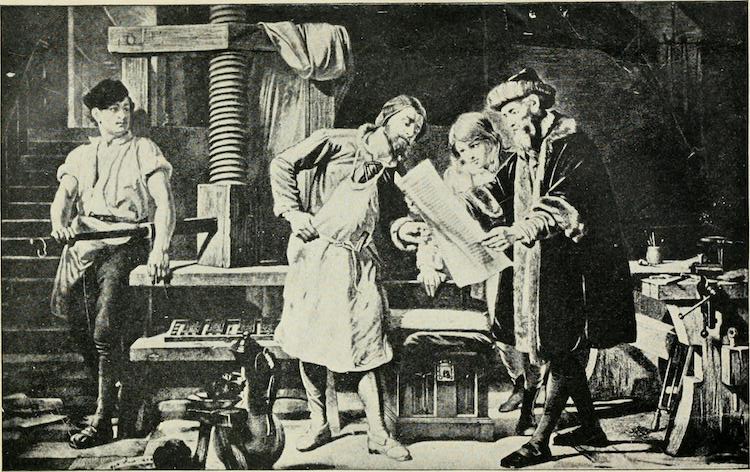

Photo: Gutenberg Taking an Impression (Public domain)

Johannes Gutenberg is considered the father of the printing press—there’s even one named after him. But his invention didn’t appear until 150 years after Chen and 78 years after Baekun.

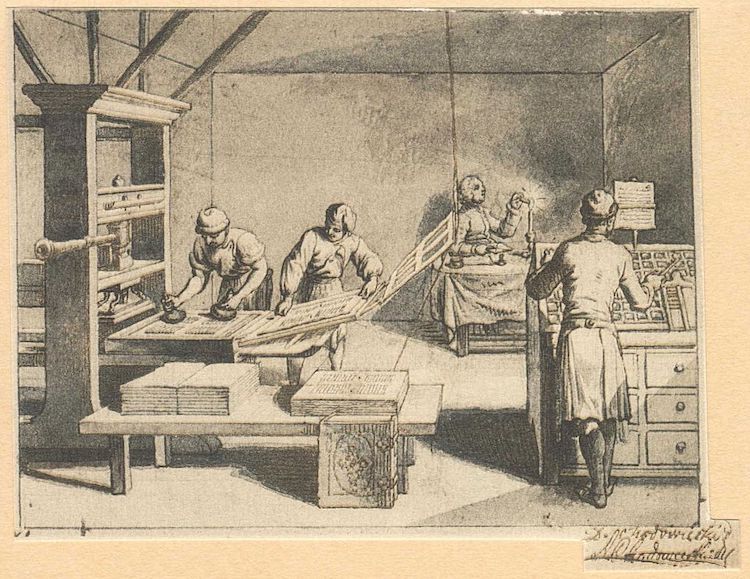

Gutenberg was a political exile from Germany and began experimenting with printing while living in France. By 1450, he had returned to his Mainz home and developed the famous Gutenberg press.

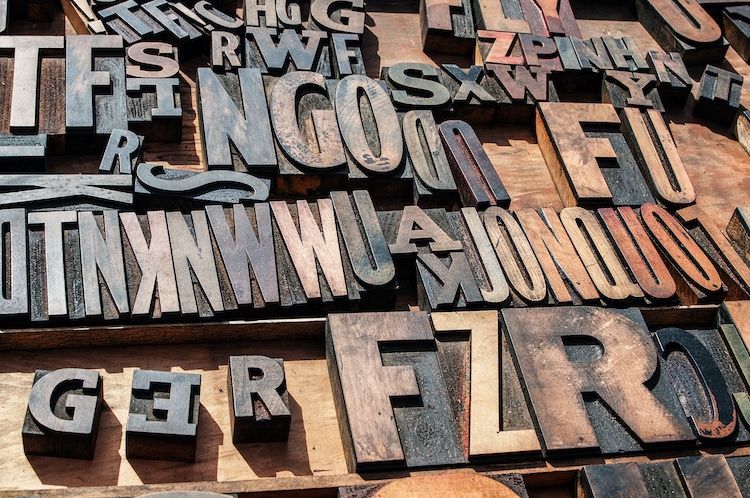

The Gutenberg printing press had several innovations on Chen’s machine. The most notable is that the formerly wooden blocks were now made of metal. Additionally, each letter was its own block, and those blocks were produced on a large scale. To replicate the type in such quantities, brass molds were created and then had molten lead poured in them. They fit together in a way that the lines of the letters were consistent and appeared uniform on paper.

There were other aspects of the Gutenberg press that made it one of the world’s most successful innovations. Gutenberg developed his own ink that stuck to metal, and he repurposed wine and olive presses—something used to press grapes for wine and olives for oil—into a means of flattening paper.

Photo: Gun Powder Ma (CC BY-SA)

So, how did the Gutenberg press work? The crux of the invention was a heavy wooden screen with a long handle used to turn it. When rotated, it would apply downward pressure onto the paper which was laid on top of the type and wood platen.

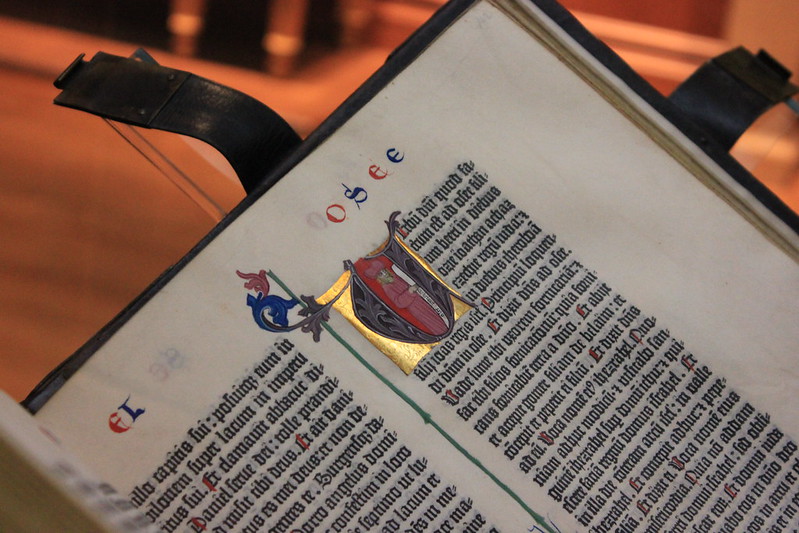

The Gutenberg Bible

The first thing to come out of Gutenberg's print shop was the Bible. Known today as the Gutenberg Bible, he printed between 150 and 180 copies that featured double columns of text and some of the letters in color. Crafting this Bible was no small feat; Gutenberg used 300 letter blocks and 50,000 sheets of paper.

Since the book's printing in 1452, many of its fragments remain, but there are only 20 complete copies left.

How Culture Changed Because of the Gutenberg Press

By having a way to quickly—and now inexpensively—reproduce the written word, an era of mass communication began. Books, which were once a symbol of wealth and status, could reach the commoner, and convey information and ideas that threatened those in power.

The expansion of literature, along with eyeglasses (invented around the 12th century), increased literacy in Europe and beyond. Now, education and reading were not just for the elite class, but an emerging middle class as well.

Related Articles:

How You Can Keep the Long Tradition of Block Printing Alive Today

World’s Oldest Multicolor Book, a Chinese Calligraphy & Painting Manual, Now Available Online

200-Year-Old Historic Books Reveal Hidden Fore-Edge Paintings