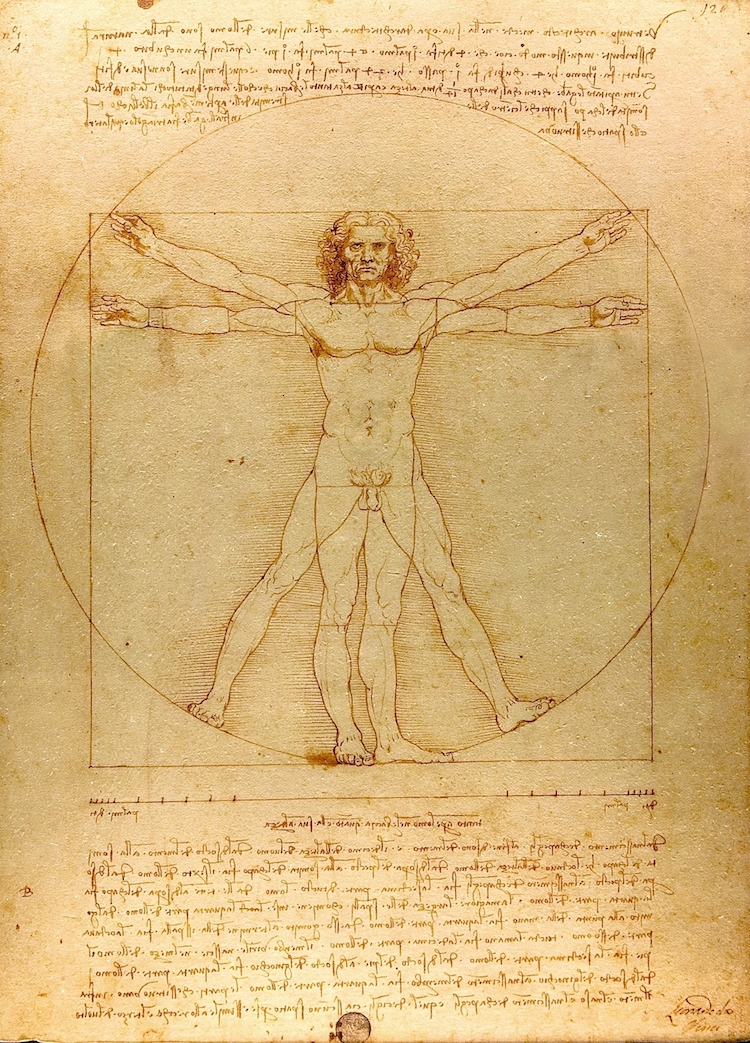

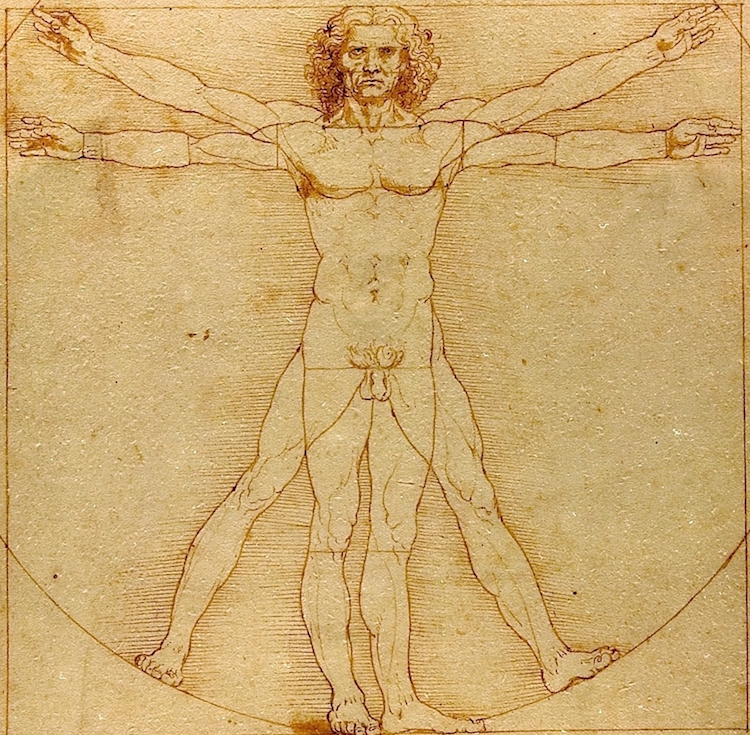

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Vitruvian Man” (ca. 1492) (Photo: Lucnix via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

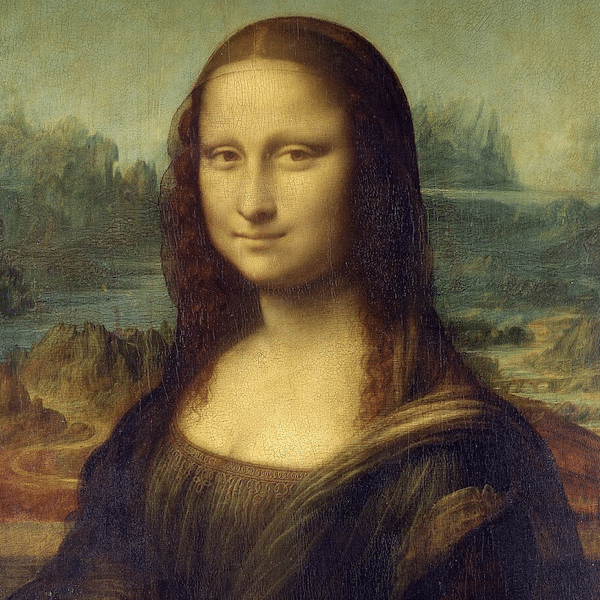

As a master of the arts, sciences, and everything in between, Leonardo da Vinci is often referred to as a “Renaissance man.” While the polymath is perhaps most well-known for his masterpieces The Last Supper and Mona Lisa, it is his scientific sketches that impressively illustrate the encyclopedic knowledge and eclectic interests that have come to define him.

The Vitruvian Man, a late 15th-century drawing, is a prime example of such work. Intended to explore the idea of proportion, the piece is part work of art and part mathematical diagram, conveying the Old Master's belief that “everything connects to everything else.”

What is the Vitruvian Man?

Title | Vitruvian Man |

Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

Year | c. 1490 |

Medium | Pen, brown ink and watercolor over metalpoint on paper |

Size | 13.5 in × 9.6 in (34.4 cm × 24.5 cm) |

Location | Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, Italy |

Leonardo drew the Vitruvian Man, also known as “The proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius,” in 1492. Rendered in pen, ink, and metalpoint on paper, the piece depicts an idealized human figure, a nude male, standing within a square and a circle. Ingeniously, Leonardo chose to depict the man with four legs and four arms, allowing him to strike 16 poses simultaneously.

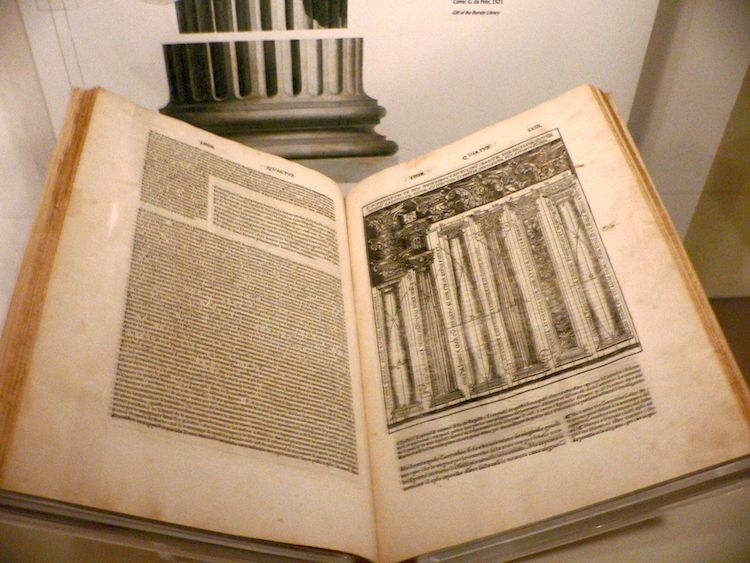

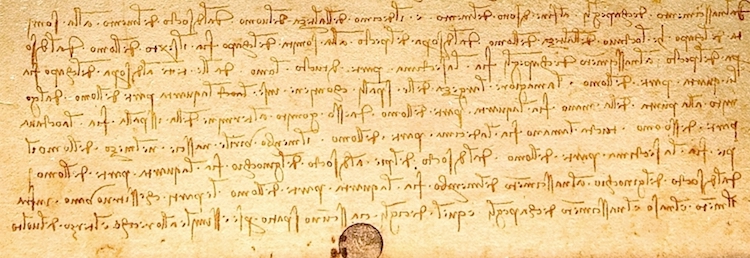

The Vitruvian Man is based on De Architectura, a building guide written by the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius between 30 and 15 BC. While it is focused on architecture, the treatise also explores the body—namely, the geometry of “perfect” human proportions—which appealed to Leonardo's interest in anatomy and inspired his drawing.

“De Architectura” by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (Photo: Mark Pellegrini via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Leonardo and Human Anatomy

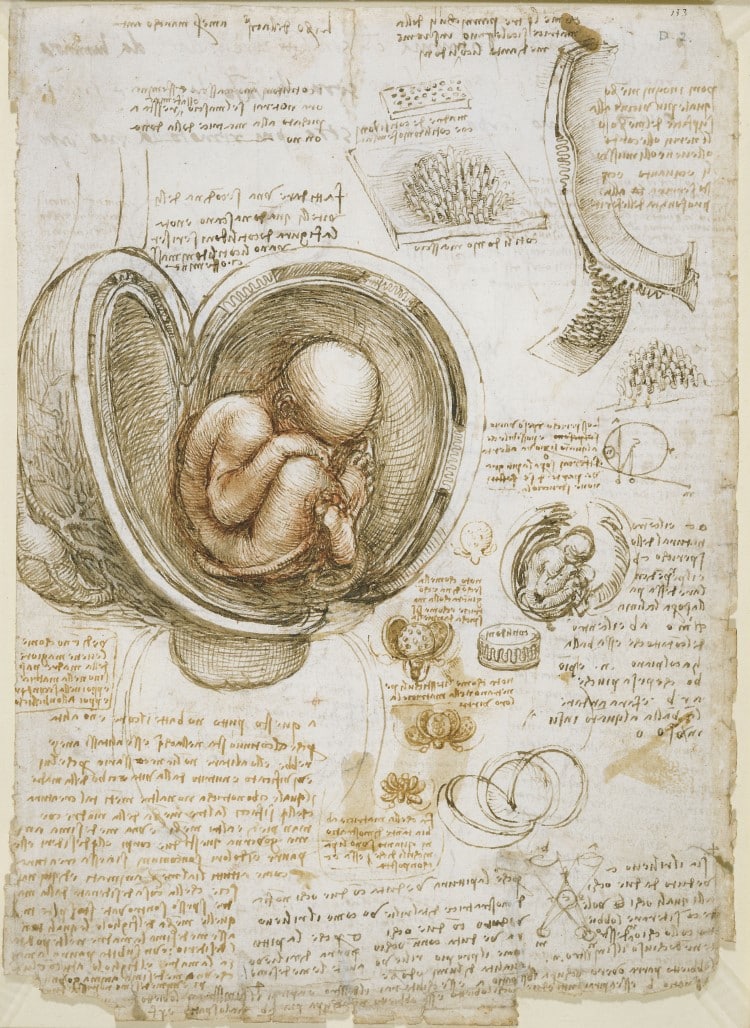

Photo: Leonardo da Vinci via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Early in the Italian Renaissance, theorists like Leon Battista Alberti wrote about the importance of artists being well-versed in the workings of the human body. Leonardo's own interest in anatomy began early in his career while he was still an apprentice. He is still considered one of the most important anatomists of the time.

Leonardo dissected over 30 corpses to study human anatomy in detail. His meticulous notes are an incredible testament to his scientific mind. While his initial anatomical drawings focused on the skeleton and musculature, Leonardo then progressed into thinking about the mechanics of the human body.

He wasn't just interested in how things looked but also how they functioned. His fascination with the human form, its symmetry, and its proportions was tied to his quest for knowledge. While during this lifetime, Leonardo kept his anatomical drawings to himself, they've since been published widely. In fact, many consider them the earliest examples of scientific illustration.

What are the “perfect” proportions?

Two blocks of backward-written text accompany the drawing. So, what does the Viturian Man text say? In the first section, Leonardo notes that, according to Vitruvius, these are the measurements of the ideal body:

- four fingers equal one palm

- four palms equal one foot

- six palms make one cubit

- four cubits equal a man's height

- four cubits equal one pace

- 24 palms equal one man

Additionally, the first set of notes also specifies: “If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the center of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle. The length of a man's outspread arms is equal to his height.”

In the second block of text, the artist describes the model body as fractions:

- “From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man's height”

- “From the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height”

- “From the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man”

- “From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be the seventh part of the whole man.”

- “From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man.”

- “The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man.”

- “From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man”

- “From the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighth part of the man.”

- “The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man”

- “The beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man”

- “The foot is the seventh part of the man”

- “From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man”

- “From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man”

- “The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and like the ear, a third of the face”

The Vitruvian Man Today

Since 1822, the Vitruvian Man has been a part of the permanent collection of the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, Italy. As it's too fragile to be on display, the piece is rarely exhibited. One of the rare times it went on display was when the Louvre borrowed it in 2019 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death.

However, even while concealed, the drawing remains a key part of their collection and, ultimately, one of the most important works of the Italian Renaissance.

Photo: robodread/Depositphotos

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the Vitruvian Man important?

Leonardo da Vinci's artwork is considered the epitome of Italian Renaissance ideas in that it has both artistic and mathematic value. The image shows the well-rounded nature of scholars and creatives during this time in history and their thirst for knowledge.

Why was the Vitruvian Man created?

Leonardo was a skilled anatomist who was fascinated by the human form. Vitruvian Man was a way for him to explore the symmetry and proportion of the human body, as well as its mechanics.

Where is the Vitruvian Man now?

Leonardo's Vitruvian Man has been in the collection at Venice's Galleria dell'Accademia since 1822. Due to its fragile nature, it's rarely put on display.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Top 10 Cities to Visit If You Absolutely Love Art

The Meaning Behind Michelangelo’s Iconic ‘David’ Statue

Virtual Tour of Florence’s Famed Uffizi Gallery Lets You Explore the Museum Online

The Significance of Botticelli’s Renaissance Masterpiece ‘The Birth of Venus’