Rembrandt, “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” 1632 (Photo: Mauritshuis, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

A decade before Rembrandt produced his masterpiece The Night Watch, he was a newly established portrait painter in the Dutch Republic. His first major commission in Amsterdam was a striking painting of a doctor performing a public dissection before a group of fascinated spectators.

Entitled The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, this large group portrait is considered an early triumph for the 26-year-old Rembrandt. It not only exemplifies the style and techniques of the Dutch Golden Age but also demonstrates the artist's theatrical approach to a genre that was typically quite static.

Here, we will take a close look at Rembrandt's early masterpiece and explore the historical context in which it was made.

Who was Rembrandt?

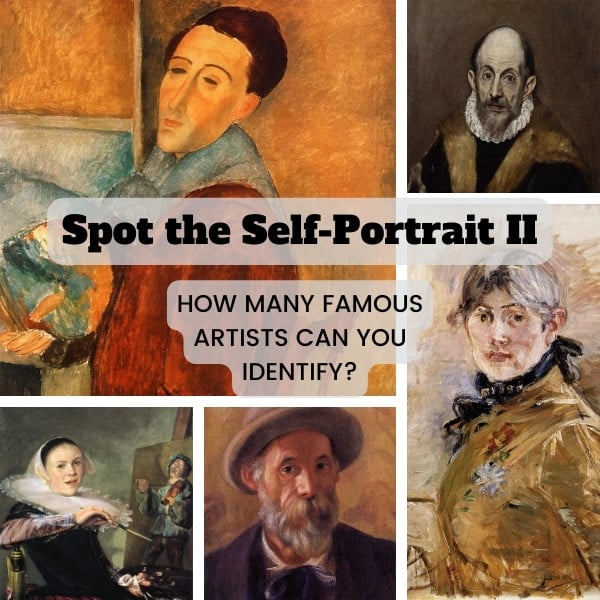

Rembrandt, “Self-Portrait,” c. 1655 (Photo: Kunsthistorisches Museum,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Dutch artist Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606 – 1669) is one of the most influential figures in the history of art. His mastery of multiple disciplines and incredible productivity helped him create one of the most extraordinary oeuvres of all time.

His initial success as a portrait painter established him as a great Dutch Golden Age painter early on in his career. He also worked on a lifelong series of self-portraits that offer a uniquely intimate look into the artist's life.

In addition to painting, Rembrandt was also a masterful printmaker who, along with artist Jacques Callot, helped transform etching into fine art. Although while he never left his home in the Dutch Republic, his reputation grew through the sales and circulation of his numerous prints.

Dissections in the 17th Century

Rembrandt, Only surviving fragment of “Dr. Deijman’s Anatomy Lesson,” 1656 (Photo: Amsterdam Museum,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

In the 17th century, anatomy lessons were open to students as well as the general public. The Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons, for instance, was allowed one public dissection a year on an executed criminal, and anyone almost anyone could attend for a fee. Dissections were often hosted in theaters so that they could accommodate copious visitors.

Commissioning The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Nicolaes Eliaszoon Pickenoy, “Portrait of Nicolaes Tulp,” c. 1650-1699 (Photo: Amsterdam Museum,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Rembrandt was just 26-years-old when he was commissioned by the Surgeon's Guild of Amsterdam to create a group portrait of public dissection, which shows how highly regarded he was as an artist at such a young age. As was customary for group portraits, all of the sitters paid a fee to be included in the painting. The more central the position—such as the case for Dr. Tulp—the higher the price.

Analysis of the Painting

Composition

Rembrandt, “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” 1632 (Photo: Mauritshuis,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The most noticeable aspect of The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp is the number of characters in the composition. Rembrandt utilizes all of the 7 x 5.5 feet canvas to give all nine figures a certain amount of importance.

The corpse, for instance, is placed in the center of the composition with Christ-like iconography. Dr. Tulp is just right from the center and several students in the background are stacked on top of each other so each of their expressions is visible to the viewer. This dynamic arrangement is unlike most group portraits and instead resembles a mise-en-scène; it's as though the figures were placed on a stage.

The Dissection

Rembrandt, Detail of “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” 1632 (Photo: Mauritshuis,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The dissection itself took place on January 31, 1632, and was performed on the body of a criminal who was executed earlier the same day. While most of the painting reveals Rembrandt's surprising amount of anatomical knowledge, the artist also took several creative liberties in the painting.

One of those liberties is excluding the preparator, the person whose function was to prepare the body for the dissection. Instead, Dr. Tulp handles the corpse directly—a task that he would not have normally done as the doctor. Additionally, in the painting, the dissection appears to be starting at the arm. However, in normal circumstances, it would have begun by opening the chest cavity, as the internal organs decay most rapidly.

The Corpse

Rembrandt, Detail of “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” 1632 (Photo: Mauritshuis,via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The corpse that Dr. Tulp is dissecting is a criminal known by the alias Aris Kindt, who was convicted and hanged for armed robbery. Rembrandt colors the body in a grayish pallor to distinguish him from the living characters. Additionally, he adds an umbra mortis—or, the “shadow of death”—over the face of the corpse to emphasize the fact that he is deceased.

Related Articles:

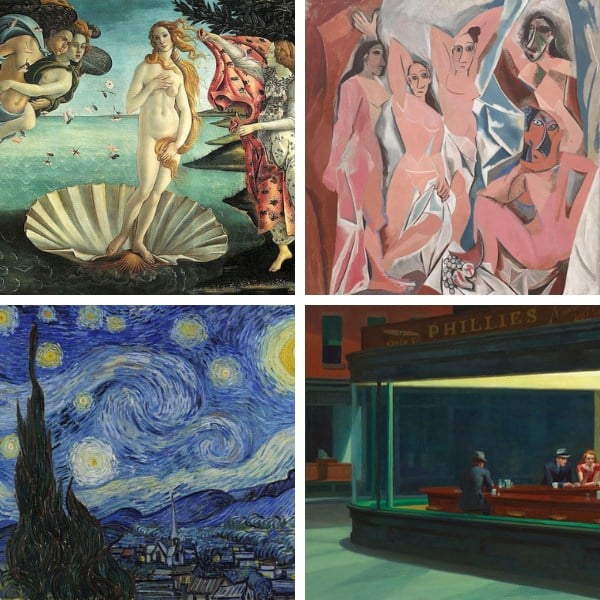

19 Famous Paintings From Western Art History Any Art Lover Should Know

15 of the Greatest Painters of All Time Whose Influences Live On Today

What Is Printmaking? A Look at the History of Creating Art in Multiples

Immerse Yourself in the Long-Running Tradition of Bathers in Art