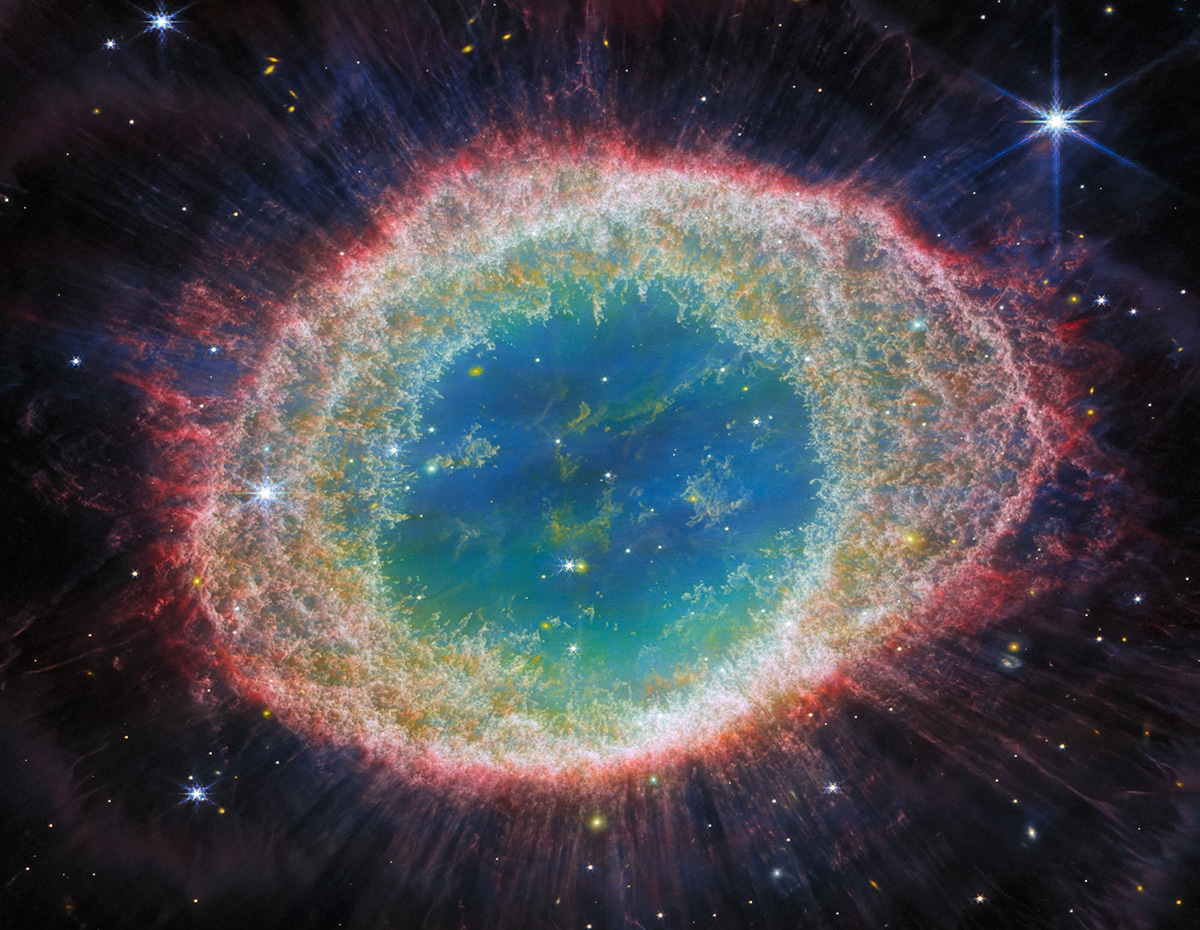

The James Webb Space Telescope imaged the Ring Nebula as never seen before. Here captured with the NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera). (Photo: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, M. Barlow, N. Cox, R. Wesson)

The James Webb Space Telescope has captured another incredible image, this time of the doughnut-shaped Ring Nebula. Since launching into space in December of 2021, the telescope has sent stunning images to Earth. These have included celestial landmarks as never seen before, including the Pillars of Creation, the Tarantula Nebula, and even the births of supernovas. Like these incredible sights, the Ring Nebula is colorful and detailed in the newly released image, which can teach astronomers about the deaths of stars.

In fact, the telescope returned two versions of its new image. One is taken with the NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and the other with the MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). In the photos, the twisty filament structure of the inner ring is exposed, looking almost like clouds. Twenty thousand dense globules within the ring hold molecular hydrogen. The ring itself is made of ten or more arcs. There is also a thin ring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Inside the ring is hot gas. The nebula itself is actually a dying star, which is on its way from a red giant to a white dwarf.

Roger Wesson from Cardiff University explained in a NASA statement: “Planetary nebulae were once thought to be simple, round objects with a single dying star at the center. They were named for their fuzzy, planet-like appearance through small telescopes. Only a few thousand years ago, that star was still a red giant that was shedding most of its mass. As a last farewell, the hot core now ionizes, or heats up, this expelled gas, and the nebula responds with colorful emission of light. Modern observations, though, show that most planetary nebulae display breathtaking complexity. It begs the question: How does a spherical star create such intricate and delicate non-spherical structures?”

Only 2,000 light years from Earth, the Ring Nebula is in the middle of the constellation Lyra, and it has been known since 1779. Binoculars and amateur telescopes can easily see it. “When we first saw the images,” Wesson elaborated, “We were stunned by the amount of detail in them. The bright ring that gives the nebula its name is composed of about 20,000 individual clumps of dense molecular hydrogen gas, each of them about as massive as the Earth. Within the ring, there is a narrow band of emission from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs—complex carbon-bearing molecules that we would not expect to form in the Ring Nebula. Outside the bright ring, we see curious ‘spikes' pointing directly away from the central star, which are prominent in the infrared but were only very faintly visible in Hubble Space Telescope images. We think these could be due to molecules that can form in the shadows of the densest parts of the ring, where they are shielded from the direct, intense radiation from the hot central star.”

While the MIRI image shows the molecular halo, the NIRCam gives sensational internal detail. These two images far outstrip the 2013 version by the Hubble Telescope, which predated Webb. The advances are so clear that it would be easy to forget how revolutionary Hubble was. Yet the leaps and bounds of space exploration continue, with more discoveries around the corner each year.

The James Webb Space Telescope has captured another incredible image, this time of the doughnut-shaped Ring Nebula.

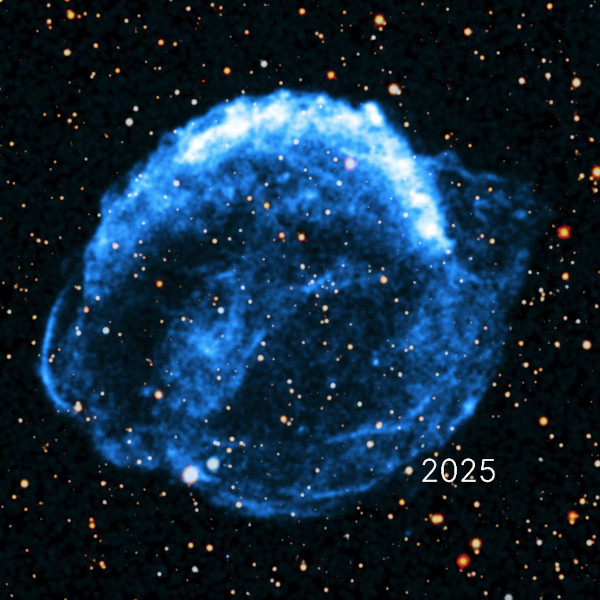

The Webb Telescope's MIRI image. (Photo: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, M. Barlow, N. Cox, R. Wesson)

The image is even more stunning than the Hubble Telescope version from 2013.

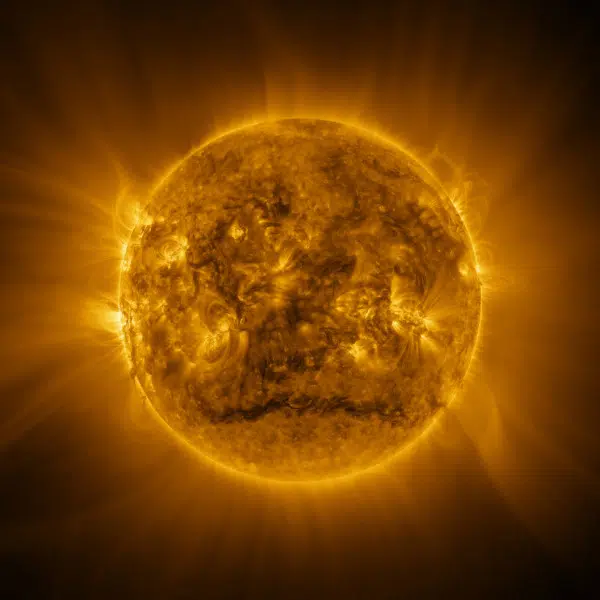

The Ring Nebula as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2013. (Photo: NASA, ESA, and C. Robert O’Dell (Vanderbilt University))