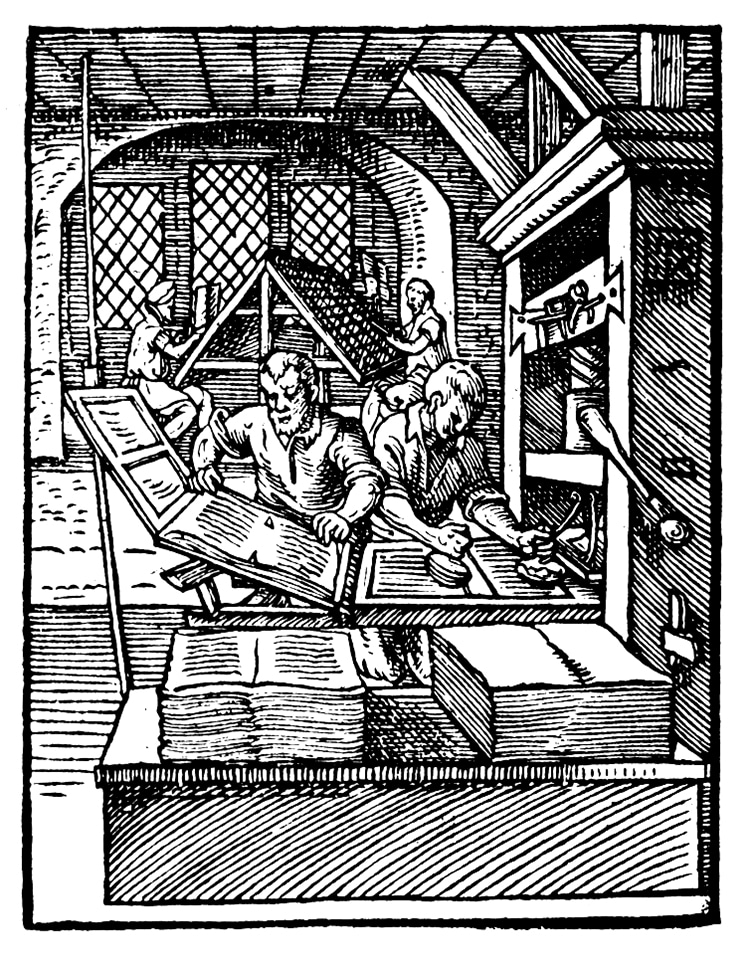

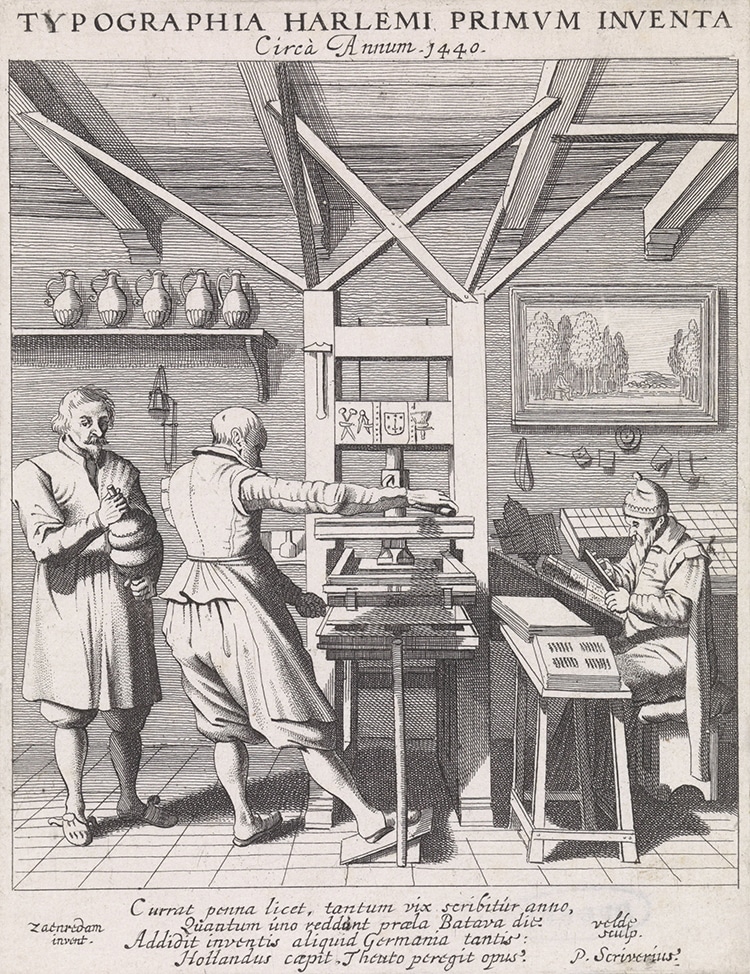

A printers workshop, 1568. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

The Emergence of Minuscule Letters

Paleography is the study of historical handwriting, and paleographers have traced how the modern type cases (sometimes misnomered as fonts) came into being. If you have seen an Ancient Roman inscription, you probably noticed that the Latin alphabet was carved in capital letters of equal size. This writing is known as Roman majuscule—majuscule meaning an all-capital script.

As the Romance languages developed out of Latin, the written alphabet also evolved. After the fall of Rome, many Latin texts in the early Middle Ages used a style known as uncial script—more rounded capitals as seen in Gothic fonts. A new type of script known as half-uncial also developed around the same time. Also rounded, this script changed the form of some letters to resemble the lowercase letters of today: the letters b and d acquired their long stems in this form. Both scripts were used throughout the medieval period.

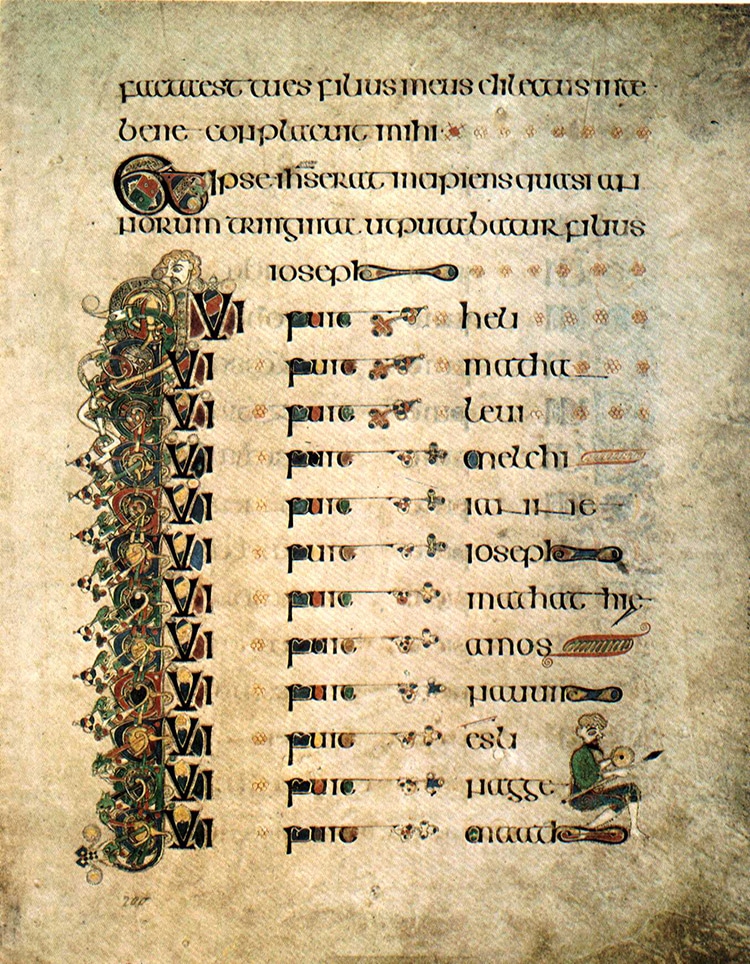

The famous Irish “Book of Kells” was written in uncial script circa 800 CE. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

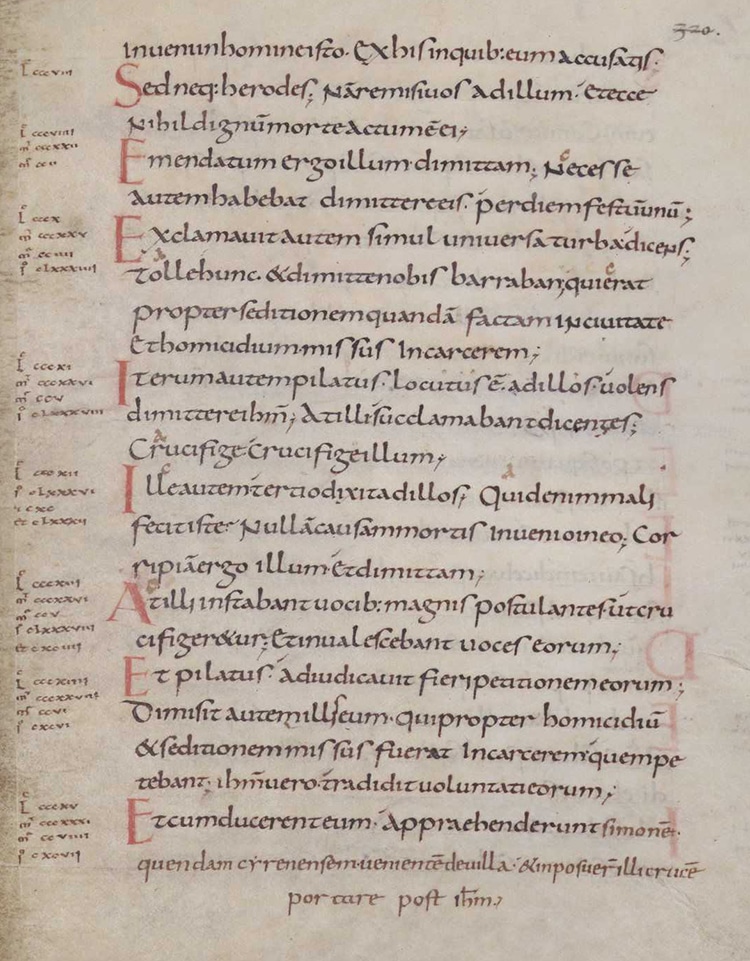

Page of a medieval Gospel written in Carolingian minuscule. (Photo: Cropped from Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Type and the Printing Press

A Dutch printing press in the 17th century. Note the type cases behind the man on the right. (Photo: Stock Photos from EVERETT COLLECTION/Shutterstock)

In 1439, Johannes Gutenberg introduced the letterpress printing process to Europe, and his invention quickly spread. The early printing press used movable metal type which could be painstakingly arranged to print a text. Each letter was an individual piece, and printers would keep many sizes and fonts on hand. Writing each word backwards, typesetters bound a page's worth of words together in a frame. Ink was then applied to the frame, and the printing press then pressed it into paper. While still a laborious process by our standards today, the ability to quickly produce multiples of a work was revolutionary.

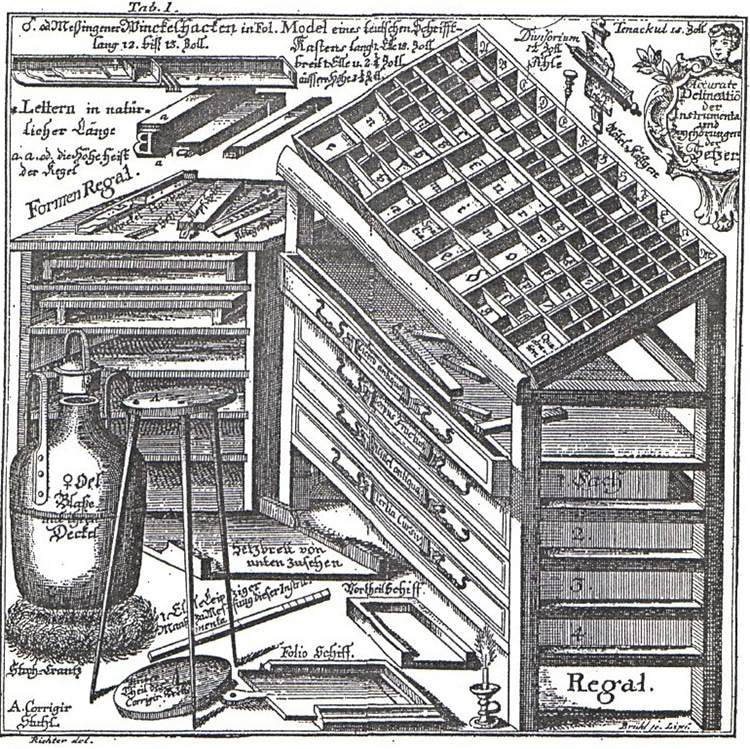

Metal movable type sorted in a case. Type is being assembled in a frame for printing. (Photo: Cropped from Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

A typesetter's sorting cases, 1740. (Photo: Cropped from Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

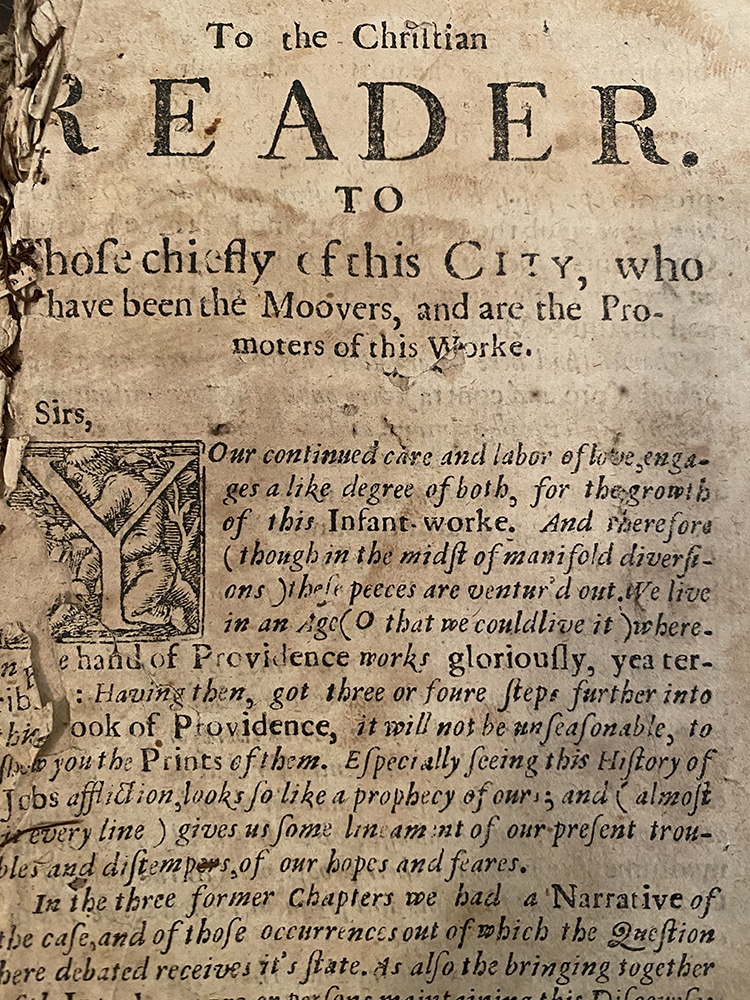

An example of printed typeface using mixed majuscule and minuscule scripts printed in London, 1656. (Photo: Madeleine Muzdakis / My Modern Met)

Related Articles:

Letterpress Printing: From Its Beginnings to the Artisan Revival Going on Today

16th-Century Calligraphy Manual Available for Free Download

Designer Creates Whimsical New Font That Changes Shape as You Type