Photo: tete_escape via depositphotos

In this day and age, it might be hard to remember a time when artworks weren’t available instantly. There was no print on demand or posters that one could easily get and hang on their wall. Printmaking changed this; artists were suddenly able to replicate an image multiple times, therefore making it easier to expose a wide audience to their work.

So just what is printmaking? This artistic practice transfers ink from a matrix onto material—typically paper—making multiple impressions of the same image. Matrixes can be made of different materials, including wood, metal plates, linoleum, aluminum, or fabric. While there are different printmaking techniques (each having its own distinct characteristics), the end result is the ability to make several impressions of a single image.

In modern times, prints are issued in editions. Each edition will have a limited number of impressions, though artists sometimes issue open editions. Once the edition is done being printed, the matrix is destroyed and every single impression is considered an original work of art. Traditionally, once printmaking took off, prints were also often used to illustrate books or were sold in small bound collections.

To get a sense of what is possible with prints, let’s look at some of the most popular traditional and modern printmaking techniques. Woodcut, engraving, and etching are all techniques that have a long history, even dating back to the 5th century CE. Techniques that have gained popularity in modern times include lithography and screen printing. We'll explore each technique to get a sense of how printmaking has made an impact on art.

Woodcut

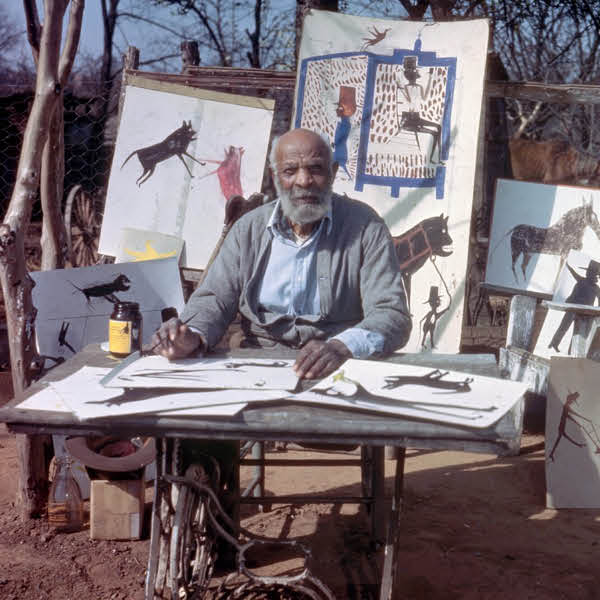

“Plum Garden at Kameido” by Hiroshige, 1857. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

As the oldest form of printmaking, woodcut has a long, rich history. Also known as woodblock printing, it is widely used in Asia. The technique has roots in China, where it was used to print on textiles.

This type of relief print is created by carving a design into a thick block of wood. The design can either be drawn directly on the block or sketched on a piece of paper and glued or transferred to the wood. Knives, chisels, and gouges are then used to bring out the image. For large prints, multiple blocks are used, with the image being assembled together in the printing process. Ink is rolled over the entire block, with the raised parts retaining the ink and then transferring the image to paper.

Woodblock printing has particular significance in Japan, where its distinct aesthetic formed a genre called ukiyo-e. These prints, produced between the 17th and 19th centuries, paint a tale of the culture through depictions of landscapes, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, and scenes from folk history. Great artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai, creator of The Great Wave Off Kanagawa, emerged during this period. These prints would greatly influence the way that the West viewed Japan and had a profound impact on artists like Van Gogh and Monet.

Engraving

“Melencolia I” by Albrecht Dürer, 1511. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Engraving is a type of intaglio printmaking where images are incised into a metal plate using a tool called a burin. It became popular in 15th century Europe and was first seen as an extension of the work that goldsmiths already did to decorate silver pieces.

Copper and zinc are the two most common materials used for the plate. They are polished to a shine and then the burin is used to create fine lines across the surface. A burin is a steel shaft with a sharp, angled tip set into a wood handle. Different size burins allow the engravers to create lines of different widths. Skilled artists can also make curved lines and use hatching and dots to give dimension and shade to the work.

Once the plate is fully engraved, it is covered in ink and a cloth ball is used to gently press the ink into the grooves. The excess ink is then cleaned away so that when the plate is run under the heavy printing press, the pressure causes the ink in the lines to transfer to the paper.

German artist Albrecht Dürer is one of the great masters of engraving. Active in the 15th and 16th centuries, his engravings were extensions of his paintings and drawings. Highly refined, Dürer’s prints prove that complex and detailed drawings could be expertly executed as engravings.

Etching

“Self-portrait leaning on a Sill” by Rembrandt, 1639. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Yet another type of intaglio printmaking, etching dates back to the 3rd millennium BCE where the technique was used to incise designs on jewelry. Its popularity in printmaking arose in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, eventually overtaking engraving as a preferred method.

Etching uses copper, iron, or zinc plates as a base. Once the plate has been polished and is free from imperfections, a layer of acid-resistant wax coats the surface. Artists then use a stylus called an etching needle to draw their design in the wax by exposing the metal. After the drawing is complete, the plate is either dipped in acid or acid is poured over the entire surface.

The acid eats away at the exposed lines, creating grooves. Printmakers control the depth of these lines based on how long the acid is left on the plate. To create different groove depths—which produce lighter or darker lines—parts of the plate can be bathed in acid for different times. This gives engravings interesting tonal qualities.

Once the acid has worked its magic, the wax is removed and the plate is inked in the same manner as an engraving. When run through the press, the lines then transfer to paper. Etching overtook engraving in popularity because, aside from having to use chemicals, it was much easier. Using a burin takes quite a bit of skill, while even novice artists are able to work with a stylus to produce a satisfactory design.

Rembrandt is particularly known for his etchings. This Dutch Old Master transformed etching into a new and relatively unknown technique into a high form of art. He successfully used his prints to make his name internationally at a time when most of his paintings never left Holland and he is still considered one of the greatest etchers in history.

Lithography

“Ambassadeurs – Aristide Bruant” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1892. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

At the very end of the 18th century, a new printmaking technique took hold. Lithography relies on the fact that oil and water don't mix and was created by a German actor as a way to cheaply produce theatrical works.

To create a lithograph, the artist starts with either a stone slab known as lithographic limestone or a metal plate typically made of zinc or aluminum. The artist first draws their image on the slab using an oil-based crayon or ink. Once complete, the entire slab is covered in a mixture of gum arabic and acid, which fixes the drawing to the surface. It also penetrates the parts of the stone not covered in the drawing, creating a layer that will absorb water and repel ink.

Once the solution is cleared from the slab, the lines of the drawing are also wiped away. It is then treated with water, which is absorbed into the blank areas. This ensures that when ink is placed across the plate, it will only adhere to the lines of the initial drawing. At this point, a damp piece of paper is laid over the slab, which is then covered with a board and several sheets of newsprint for padding. A flatbed press applies equal pressure across the slab and transfers the image. For multicolor lithographs, the same piece of paper is run across different stones, with the printmaker taking care to align the images.

Toulouse-Lautrec is a prime example of an artist who took full advantage of this new technology. His colorful lithographs of Parisian nightlife are a fascinating glimpse into the late-19th century French capital.

Screen Printing

Screen printing, as we know it today, was pioneered at the beginning of the 20th century. It's sometimes called silkscreen because traditionally silk was used in the technique. The printmaking process calls for a mesh to be used to transfer ink onto a surface except for where it's blocked by a stencil containing the design. Screen printing was pioneered in China during the Song dynasty when silk was used and then spread to Europe once silk mesh was readily available there.

Screen printing is very versatile because the stencil can be made out of a wide variety of materials. The stencil is then fixed to the screen and then its entire surface is coated in a photo-reactive chemical. This serves to fix the design to the mesh once it's been exposed to UV light. The stencils are then removed and the screen is cleaned.

A piece of paper is placed under the mesh on a special screenprinting table that holds everything in place. Using a squeegee, a thick layer of ink is spread evenly across the mesh. Once the screen is lifted, it's possible to see the direct imprint of the stencil on the paper. To create a multi-color screen print, different stencils are created and the printmaker must be careful to align the paper each time a new color is passed through the screen.

Screen printing is popular culturally because, at its core, it is a fairly simple and economic printing technique that can be used to produce everything from zines to album covers to t-shirts. Pop artist Andy Warhol is responsible for elevating the artistic practice in the 1960s with his silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe and others.

Related Articles:

Unwinding the Long History of Line Art

Letterpress Printing: From Its Beginnings to the Artisan Revival Going on Today

Risograph: How a Vintage Japanese Copy Machine Became an Artistic Printmaking Tool

How Alphonse Mucha’s Sinuous Art Nouveau Posters Elevated Printmaking as an Art Form