Poster for F. Champenois Imprimeur-Editeur, 1897 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

At the end of the 19th century, a movement of “new art” swept through Europe. Characterized by an interest in stylistically reinterpreting the beauty of nature, artists from across the continent adopted and adapted this avant-garde style. As a result, it materialized in sub-movements like the Vienna Secession in Austria, Modernisme in Spain, and, most prominently, Art Nouveau in France.

The French Art Nouveau style was embraced by artists working in a range of mediums. In addition to the fine arts, like painting and sculpture, it featured heavily in architecture and decorative arts of the period. However, perhaps its most enduring legacy can be found in the poster—a commercial craft that Czech artist Alphonse Mucha helped elevate as a modern art form.

“Four Seasons,” 1897 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Alphonse Mucha's Early Life

“Crucifixion,” 1868 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1860, Alfons Maria Mucha (known internationally as Alphonse Mucha) was born in Ivančice, a small town now part of the Czech Republic. His childhood was shaped by a unique trio of influences: his Catholic upbringing, an interest in music, and his natural artistic talents. “For me,” he wrote, “the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music, or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies.”

“Portraits of Saints Cyril and Methodius,” 1887 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Though Mucha viewed these elements as interconnected, each one had a discrete and discernible influence on his artistic career and eventual success. His role in the Catholic Church, for example, helped him secure his first big commission, a Portrait of Saints Cyril and Methodius, while his fascination with music morphed into an interest in the theatre and, consequently, work as a stage designer.

It was not his religious paintings and theatrical decoration, however, that made Mucha a household name. It was, rather, the commercial illustrations he began churning out in Paris.

Artistic Success in La Belle Époque Paris

Photograph of Paul Gauguin, Alfons Mucha, Ludek Marold, Annah la Javanaise in 1896 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1888, Mucha moved to the French capital. Here, he found a support system in both the local Slavic community and in Charlotte Caron, a patron of the avant-garde arts and owner of the artist-filled Crémerie boarding house. While living in this creative hub, Mucha shifted his focus from painting and theatre to magazine illustration, a field in which he quickly found success.

The visuals he provided for contemporary publications like La Vie popular and Le Petit Français Illustré resulted in a suitable income for the 30-year-old. Soon, he was able to afford supplies and space to help him hone his craft, including a camera so he could work from photographs and a shared studio with fellow artist Paul Gauguin.

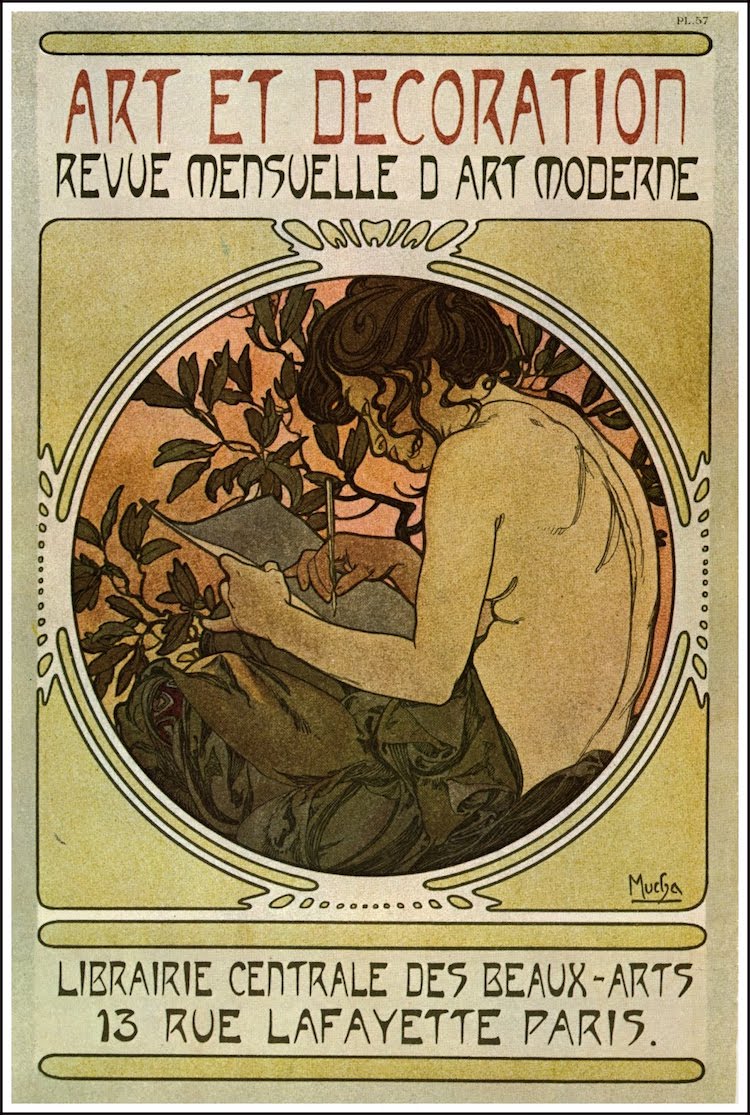

Cover from 1901 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In the early 1890s, two big breaks changed the course of Mucha's career once again. First, he began working for the Central Library of Fine Arts, an art book company that would eventually popularize the Art Nouveau style with its magazine, Art et Decoration. Secondly, and most importantly, he was commissioned to create posters publicizing the work of popular Parisian stage actress Sarah Bernhardt.

Together, these roles prompted Mucha to pursue what would become his most well-known practice: poster design.

Theatrical Posters

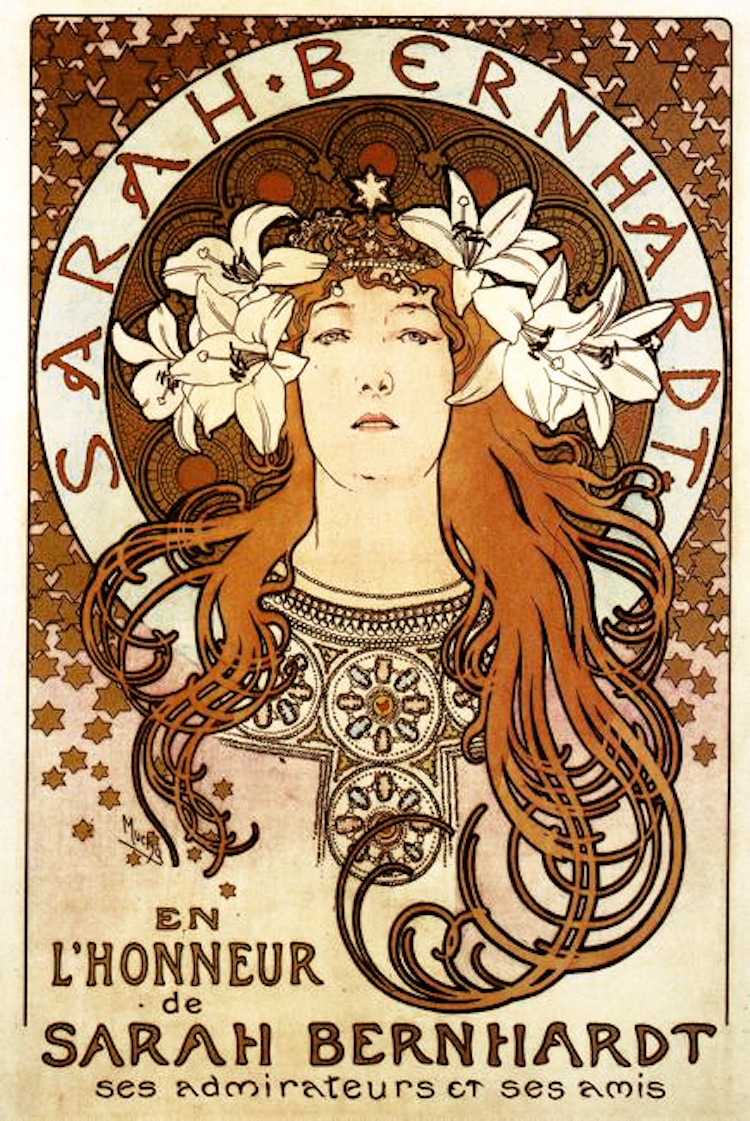

Poster of Sarah Bernhardt, 1896 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In December 1894, Bernhardt was looking for an artist to create a fresh poster for the play Gismonda. The spectacle, which starred Bernhardt, had recently been renewed for an extended run in Paris. Unfortunately, due to the fact that her request was made during the busy holiday season, her go-to team of artists from Lemercier, a popular publishing company, was not available to complete it.

Poster for “Gismonda,” 1894 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

On short notice, Maurice de Brunhoff, the manager of the firm, asked theatre-loving Mucha to step in and design the advertisement, which the artist realized as a larger than life-sized poster featuring exotic motifs, swirling silhouettes, and mosaic-inspired patterns. Posted all over Paris, this piece made Mucha a well-known artist—and secured him a contract with Bernhardt.

For six years, Mucha designed the flyers and bills for Bernardt's productions, including La Tosca and Hamlet. This role, however, was only the beginning of Mucha's liaison with lithography, which culminated in several commercial commissions.

Commercial Prints

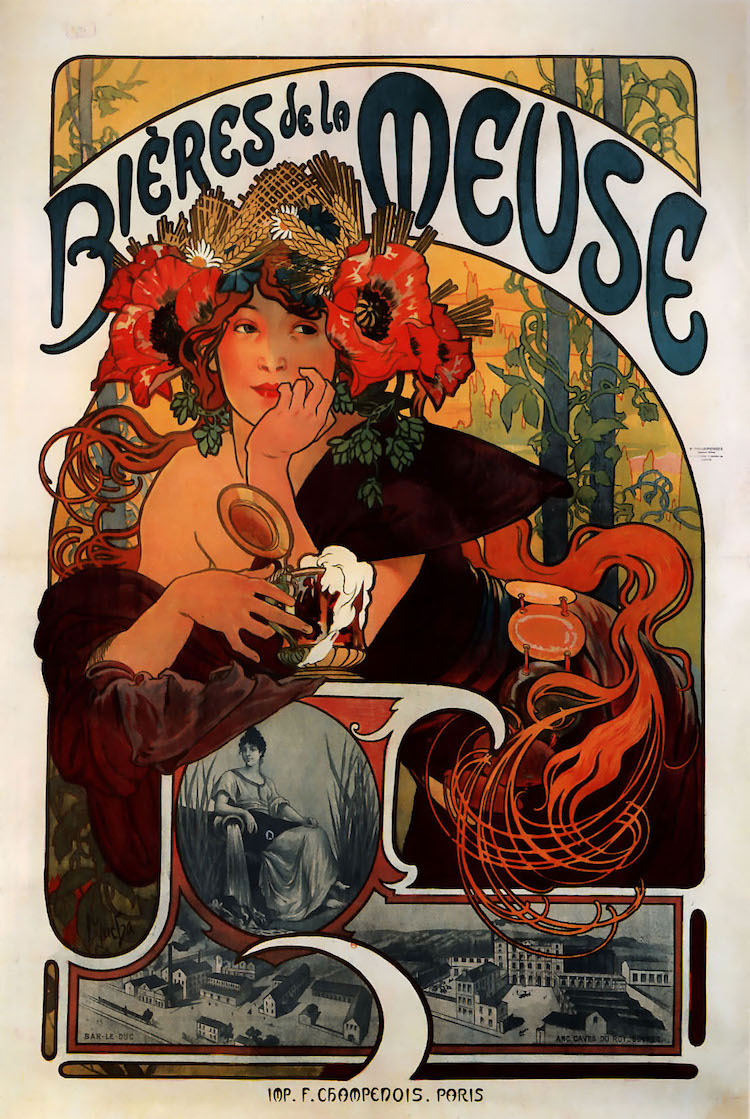

Poster for “Bières de la Meuse,” 1897 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Nestlé, Moët-Chandon champagne, and the Beers of the Meuse are just some of the many companies that hired Mucha to design their advertisements in fin de siècle Paris. Though intended to sell an eclectic range of products, these designs are all rendered in the style that Mucha had developed while creating posters for Bernardt—and one that helped popularize the Art Nouveau style.

Many of them feature conventionally beautiful, contemporary women as their subjects, whose soft, traditionally feminine features—including flowing hair, gracefully moving bodies, and fashionable, ornamental clothing—reflect the sinuous curves and nature-inspired motifs that characterized the “new art” movement.

Poster for Moët & Chandon, 1899 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In addition to pioneering the “Mucha style” of Art Nouveau, these works immensely improved printmaking's artistic reputation. Prior to Mucha, printmaking mostly existed in the realms of woodcuts, engravings, and etchings. However, in the 1890s, Jules Chéret, a French artist celebrated as the “father of the modern poster,” introduced the color lithograph. Using new techniques and technologies, artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Georges de Feure, and, of course, Alphonse Mucha, excelled in the medium, which doubled as an effective advertising tool and an alluring art form.

As a result, the distinction between mass production and fine art became fuzzy, and the Art Nouveau aesthetic quickly became an embedded and accessible aspect of everyday life.

Later Work and Legacy

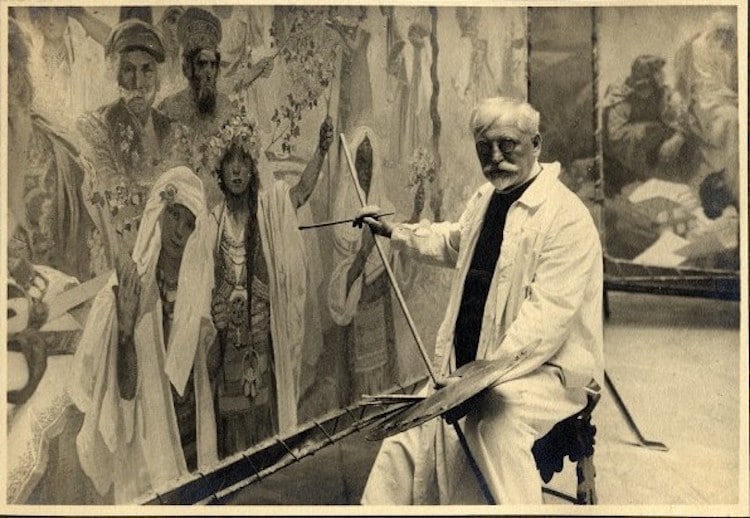

Mucha working on the “Slav Epic,” 1924 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Following the fruitful nature of his commercial career, Mucha was able to again alter his focus and work on projects that pleased him on a personal level. Specifically, he turned his attention toward history paintings, which—along with his popular, crowd-pleasing Art Nouveau creations—he exhibited during Paris' World's Fair in 1900.

Later in life, he moved from Paris to Prague, where he spent 18 years crafting his most ambitious project yet: the Slav Epic. Inspired by the artist's intention to “do something really good, not just for the art critic but for our Slav souls,” this series of 20 large-scale paintings shines a spotlight on the achievements of Slavic cultures, which he studied through years of extensive travel, research, and observation.

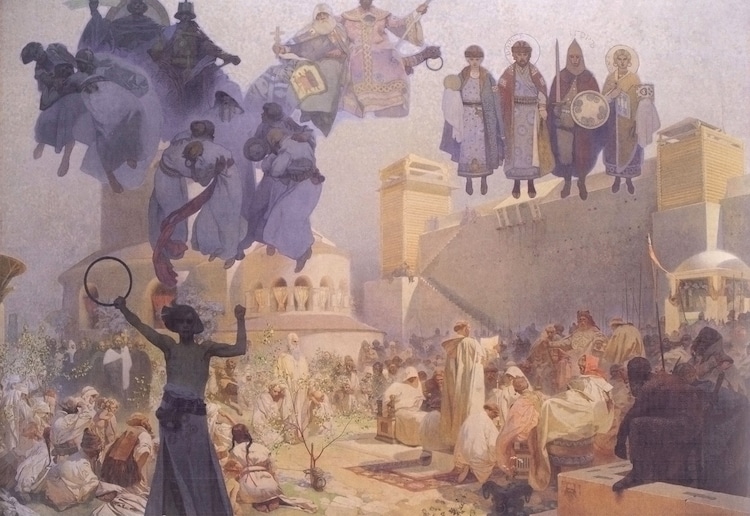

“The Introduction of Slavonic Liturgy” from the “Slav Epic,” 1912(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

A far cry from the bright and bold aesthetic of his prints and posters, Mucha considered this cycle of tempera paintings his most important life's work. In fact, though his commercial pieces are considered triumphs of Art Nouveau, he rejected the movement.”What is it, Art Nouveau?” he asked. “Art can never be new.”

Therefore, to understand Mucha's practice, it is vital to not only study his popular prints and posters, but to consider his passion projects as well. After all, it was Mucha himself who, after years of familiarizing himself with the ins-and-outs of commercial art, famously stated that “art exists only to communicate a spiritual message.”

Related Articles:

The Splendid History of Gustav Klimt’s Glistening “Golden Phase”

Art Nouveau, the Ornate Architectural Style that Defined the Early 20th Century