The History of Mexico Stock Photos from Florian Augustin/Shutterstock

For centuries, the fresco has served as an important method of mural-making. While these plaster paintings have existed since ancient times, modern artists have continued to reimagine the craft, with Mexican painter Diego Rivera at the forefront.

Equally famous for his revolutionary paintings and tumultuous personal life, Rivera remains one of modern art‘s most well-known figures. Here, we take a look at his enduring work and the events that inspired it in order to paint a fuller picture of this controversial artist.

Life and Work

“Diego Rivera with a xoloitzcuintle dog in the Blue House, Coyoacan”(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez was born in Guanajuato, a city in central Mexico, in 1886. As a young child, Rivera expressed an interest in art. By the age of 10, he was enrolled in the Academy of San Carlos, a major art academy. A few years later, he traveled to Europe to study art on a sponsorship, landing in Madrid and then Paris, where he developed friendships with leading modernist figures.

While in Paris, Rivera experimented with different styles of painting, including Cubism and Post-Impressionism. While he saw success in the French capital, he moved to Italy in 1920. After spending one year studying Renaissance frescoes, he returned to his home country, where he experienced two important milestones: meeting Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, with whom he would enter into a notoriously toxic and tumultuous relationship, and undertaking his biggest—and most political—project yet: a series of murals inspired by the Mexican Revolution.

The Mexican Mural Movement

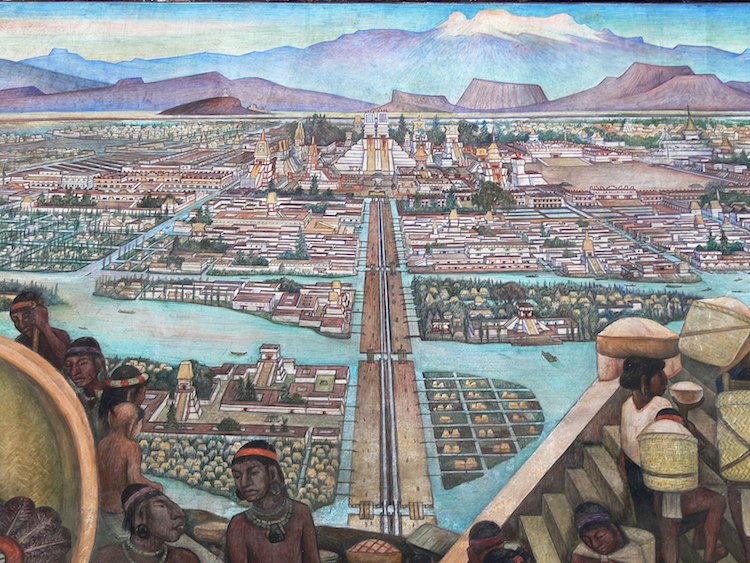

The Great City of Tenochtitlan (detail) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Rivera arrived in Mexico in 1922. At this time, the country was grappling with the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, a decade-long political crisis and Civil War that culminated in over one million deaths. Tasked with the challenges of revitalizing Mexican culture and promoting pro-Revolution ideals, the government decided to fund a public art program.

Known today as Mexican Muralism, the government employed several prominent painters for this project-turned-movement, including José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and, of course, Diego Rivera. Collectively known as “the big three,” these artists addressed major Revolutionary themes, like human suffering (a motif favored by Orozco), revolutionary heroes (Siqueiros's preferred subject), and Mexico's working-class society (Rivera's focus).

Diego Rivera's Murals

While each artist saw success, Rivera's large-scale works proved particularly popular—both in Mexico and beyond. Employing a distinctive style characterized by a bold color palette and simplified forms inspired by both Mayan and Aztec art, “Rivera created sweeping mural cycles that drew upon modernist painting styles to render heroic visions of Mexico’s past and present that captured the attention of critics and onlookers internationally.”

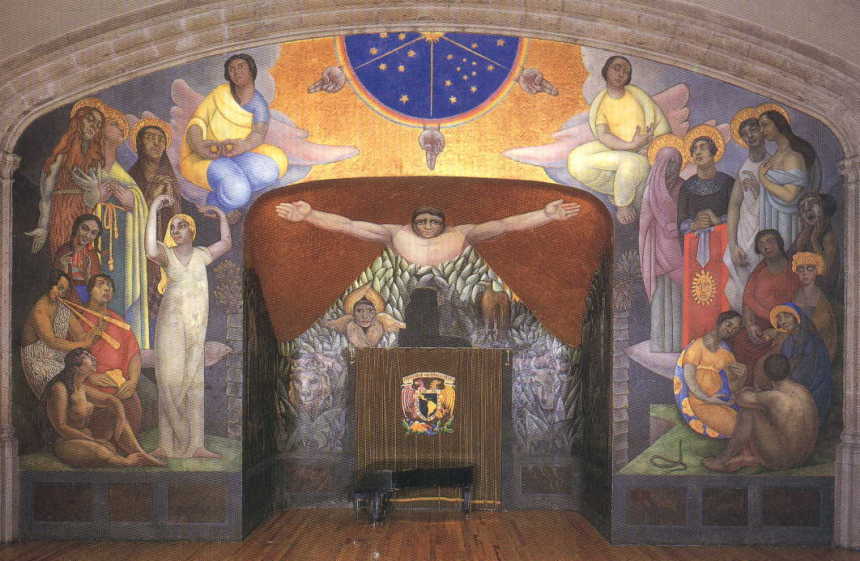

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Rivera completed politically-charged frescoes all over the world. Some of his most well-known works can be found in Mexico City's Centro Historico, or Historic Center. These include his first mural, titled Creation, in the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School as well as colossal paintings that adorn the stairways and corridors in the Palacio Nacional, or National Palace.

Rivera also completed murals in the United States. Made possible by a relationship with the American Ambassador to Mexico, this stint spawned some of Rivera's most famous pieces: The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City in San Francisco; the Detroit Industry Murals in Detroit; and Man at the Crossroads, a piece planned—though never completed—for Rockefeller Plaza in New York City.

Man at the Crossroads

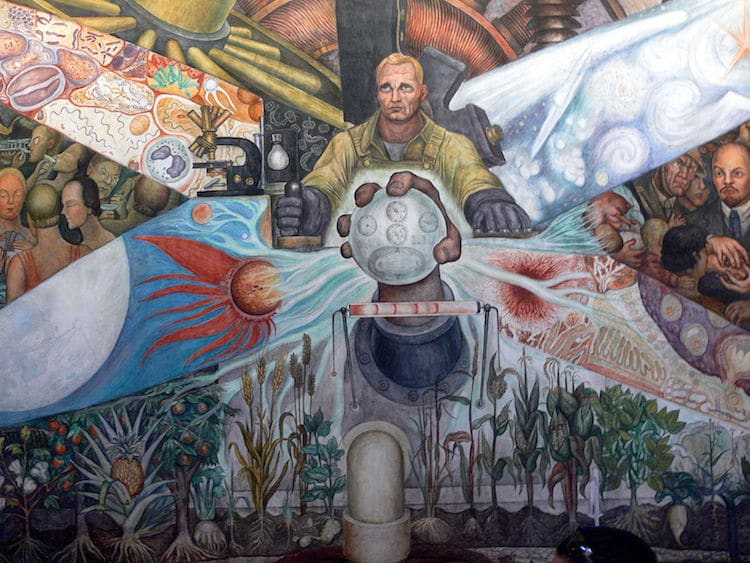

Man, Controller of the Universe (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ironically, Man at the Crossroads is perhaps Rivera's most famous work. Its design incorporated several motifs and subjects, most of which referenced contemporary culture. In the center of the composition, a workman is shown controlling a machine. This central figure is surrounded by a collage of symbols, from a fist clenching an orb adorned with atoms and cells to swirling stars and planets.

Packed with scenes referencing both society and science, Rivera explained that Man at the Crossroads illustrated humankind's search for a “more complete balance between . . . technical and ethical development.” This, however, is not the only juxtaposition explored by Man at the Crossroads. Most prominently, it conveys the contrast between capitalism and communism.

Man, Controller of the Universe (Lenin detail) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

While Rivera's plan to convey this concept was approved by the Rockefeller family, it quickly caused controversy. “Rivera’s pointedly pro-leftist subject matter—including a laudatory portrait of Vladimir Lenin—and caricatured portraits of his Rockefeller patrons riled the site’s managers, and Rivera was fired before he could complete the fresco,” the Museum of Modern Art explains.

Prior to his termination, Rivera was given the opportunity to simply sanitize the fresco's subject matter. Rivera refused, however, stating, “rather than mutilate the conception, I shall prefer the physical destruction of the conception in its entirety, but preserving, at least, its integrity.” The fresco was removed from the walls and destroyed. This, in turn, resulted in protests and boycotts around the world, leading Rivera to conclude that his art's suffering “will advance the cause of the labor revolution.”

While Man at the Crossroads was never completed, Rivera painted a smaller replica called Man, Controller of the Universe, in Mexico City's Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts).

Diego Rivera's Legacy

While Rivera's career was sprinkled with scandal until his death in 1957, his murals are regarded as key contributions to both the history of art and to modern society as whole. With his large-scale public works, Rivera communicated important political messages that challenged, mobilized, and inspired the public. In fact, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s celebrated “New Deal”—a series of projects that played a pivotal role in the aftermath of the Great Depression—would borrow this model, proving the virtue and validity of public art.

Related Articles:

Explore “La Casa Azul”: Frida Kahlo’s Famous Blue House-Turned-Museum

The Stories and Symbolism Behind 5 of Frida Kahlo’s Most Well-Known Paintings

Brooklyn Museum Announces “Major Exhibit” on the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Upcoming Exhibition Uses Frida Kahlo’s Personal Belongings to Tell Her Life Story