Since its emergence over 100 years ago, Cubism has been regarded as one of modern art‘s most famous and fascinating art movements. Cubism is closely associated with iconic artists like Pablo Picasso, whose avant-garde approach to everyday subject matter turned art history on its head.

Featuring fractured forms and topsy-turvy compositions, Cubism abandoned the figurative portrayals found in genres of art and moved toward total abstraction. This aspect—along with its unique evolution and lasting influence—has made Cubism one of the 20th century's most celebrated forms of art.

What is Cubism?

Cubism is an art movement that made its debut in 1907. Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the style is characterized by fragmented subject matter deconstructed in such a way that it can be viewed from multiple angles simultaneously.

History

At the turn of the century, Post-Impressionism and Fauvism—movements inspired by the Impressionists‘ experimental approach to painting—dominated European art. French painter, sculptor, printmaker, and draughtsman Georges Braque (1882-1963) contributed to the Fauvist movement with his polychromatic paintings of stylized landscapes and seascapes.

In 1907, Braque met Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, and designer Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). At this time, Picasso was in his “African Period,” producing primitive works influenced by African sculpture and masks. Like Braque's Post-Impressionist paintings, these pieces played with form (and sometimes color), but remained figurative.

After they met, however, Braque and Picasso began working together, deviating further from their previous styles and collaboratively creating a new genre: Cubism.

Phases of Cubism

Proto-Cubism

Before the movement was underway, both Picasso and Braque applied elements of the soon-to-be style to their respective genres. This fascinating transition into Cubism is especially apparent in two of their works: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and Viaduct at L'Estaque (1908).

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is perhaps Picasso's most famous piece from his African Period. Dated 1907, it was created on the cusp of Primitivism and Cubism, as evident in the figures' mask-like faces and the fragmented subject matter.

Viaduct at L'Estaque depicts Braque's interest in playing with perspective and breaking subjects into geometric forms—key Cubist traits.

Analytic Cubism

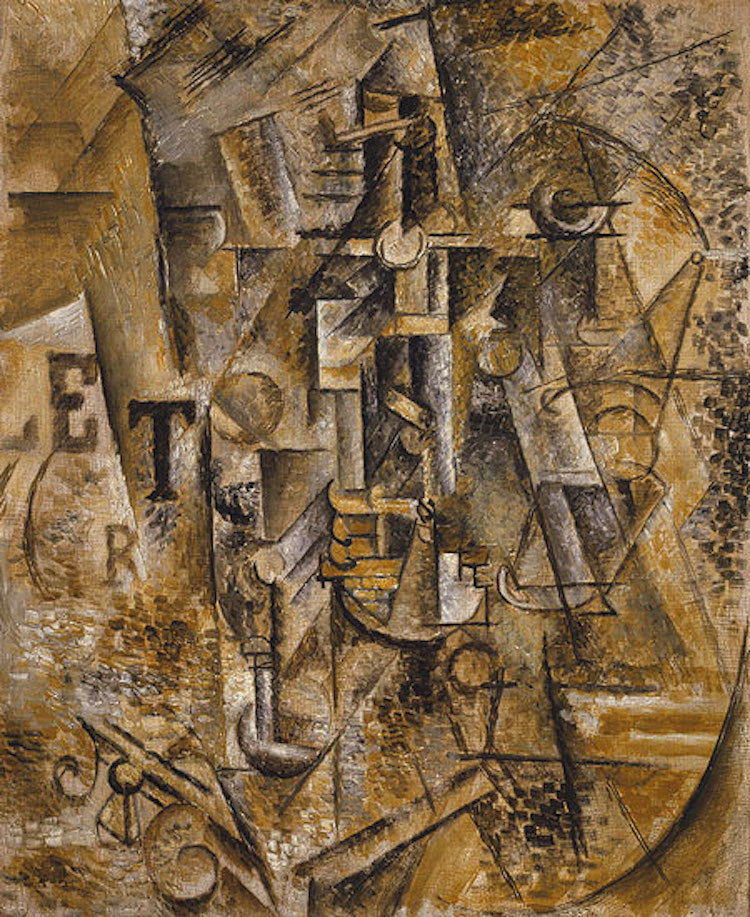

The first official phase of the movement is known as Analytic Cubism. This period lasted from 1908 through 1912 and is characterized by chaotic paintings of fragmented subjects rendered in neutral tones.

Pablo Picasso, “Still Life with a Bottle of Rum,” 1911 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons)

The fractured forms often overlap with one another, displaying the subject from multiple perspectives at once.

Georges Braque, “Still Life with Metronome,” 1909 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, PD-US)

Picasso also applied the principles of Analytic Cubism to his sculpting practice, culminating in a collection of busts and figures that emphasize the phase's experimental approach to perspective.

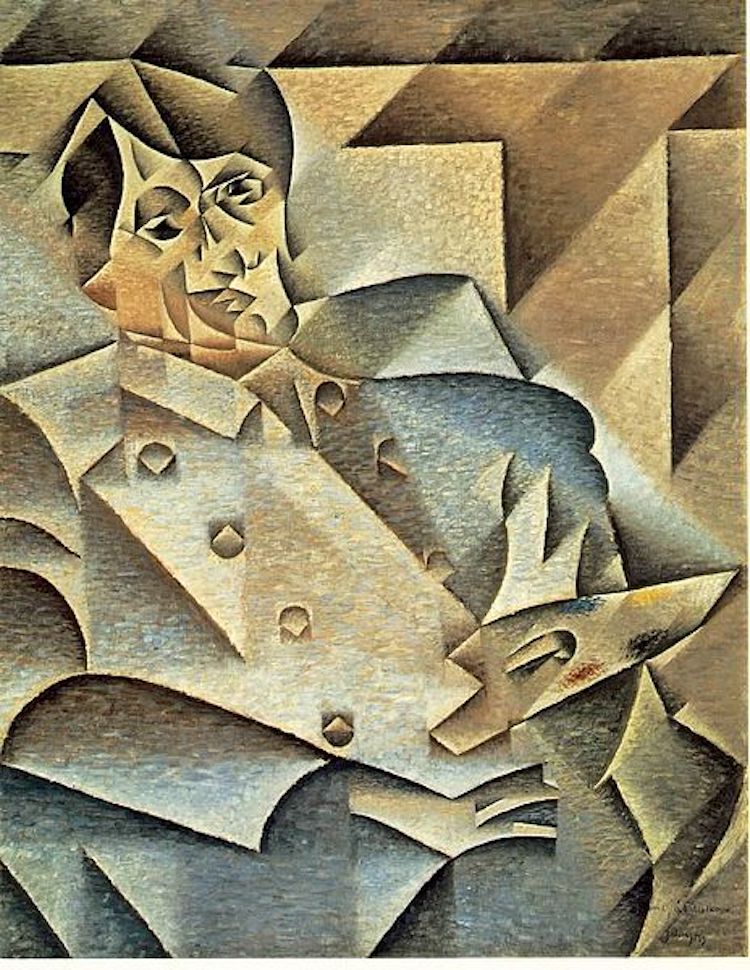

At this time, other artists interested in the avant-garde joined Picasso and Braque, including Spanish painter Juan Gris (1887-1927).

Juan Gris, “Portrait of Picasso,” 1912 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Gris would go on to become another well-known Cubist painter, particularly known for his role in Synthetic Cubism.

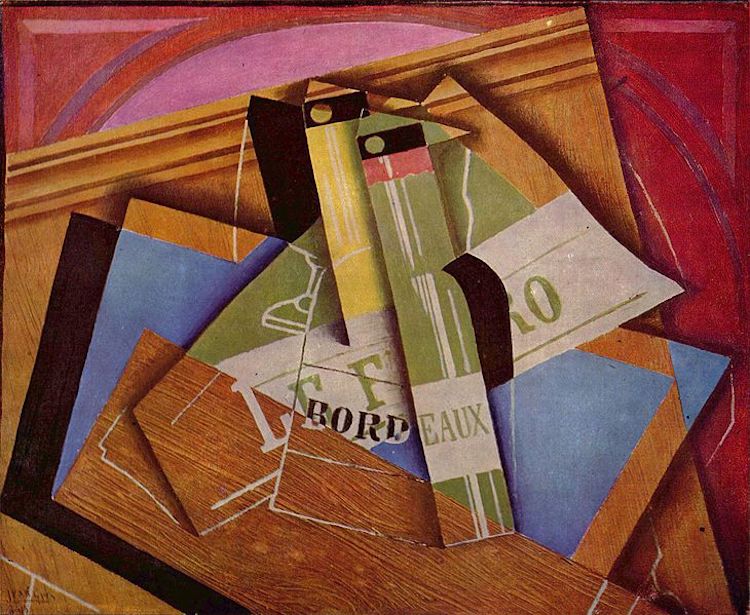

Synthetic Cubism

Synthetic Cubism is the movement's second phase, emerging in 1912 and lasting until 1914. During this time, Picasso, Braque, Gris, and other artists simplified their compositions and brightened their color palettes.

Juan Gris, “Still Life with Bordeuaux Bottle,” 1919 (Photo: The Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons Public domain)

Synthetic Cubism showcases an interest in still-life depictions, rendered as either paintings or collage art.

Pablo Picasso, “Head,” 1913–1914 (Photo: National Galleries, Edinburgh, PD-US)

Famous Cubist Artists

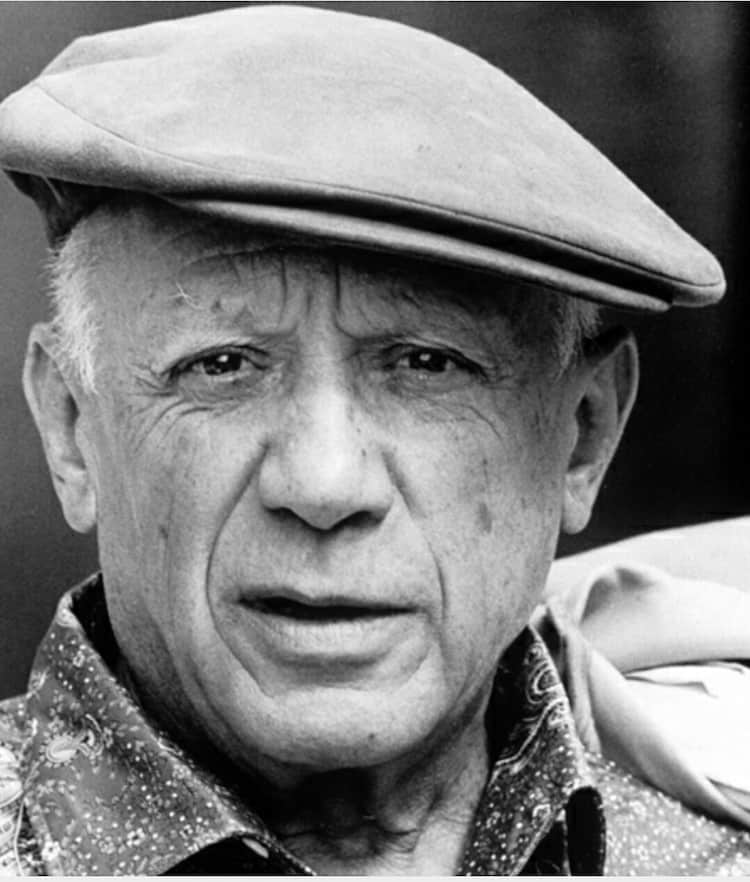

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

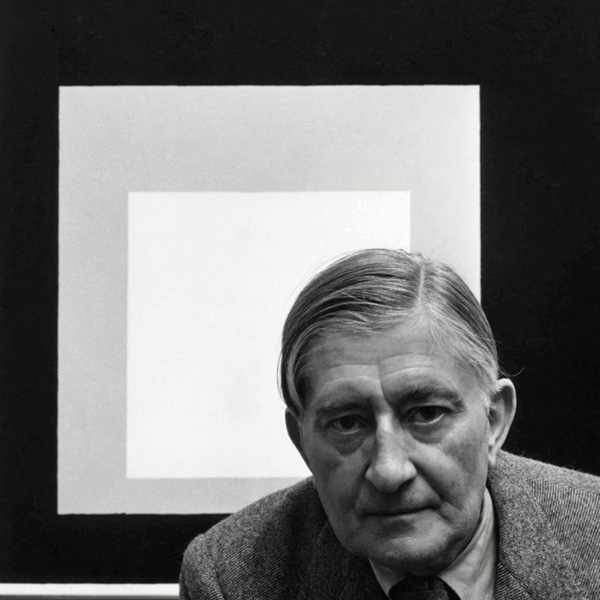

Photograph of Pablo Picasso, 1962 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

With a career that spanned 79 years and included success in painting, sculpting, ceramics, poetry, stage design, and writing, Pablo Picasso is one of the most important artists of the 20th century. While most artists are known for one iconic style, Picasso's changed several times during his lifetime. Some of his most distinct periods include the Blue Period, Cubism, and Surrealism.

Famous works of art: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), Guernica (1937)

Georges Braque (1882–1963)

Photo of Georges Braque, 1908 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

French artist Georges Braque was a pioneer of the Fauvist and Cubist art movements. During the latter, he worked closely with Picasso, developing a signature style that featured geometric shapes and simultaneous perspectives. His most notable works were still lifes and landscapes made within the Cubist aesthetic. While he was integral to the development of Cubism, his art was largely overshadowed by Picasso's worldwide fame.

Famous works of art: Still Life with Metronome (Still Life with Mandola and Metronome) (1909), Violin and Candlestick (1910)

Juan Gris (1887–1927)

Juan Gris, “Still Life Before an Open Window, Plane Ravignan,” 1915 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Spanish-born artist Juan Gris was another integral member of the Cubist art movement. His earlier works fit into Analytical Cubism, standing apart from Braque and Picasso for their distinctly vibrant color palette—a trait that was partially inspired by the colors of Matisse's paintings. Due to his emphasis on color and simplified geometric shapes, he was integral to the development of the style.

Famous works of art: Portrait of Picasso (1912)

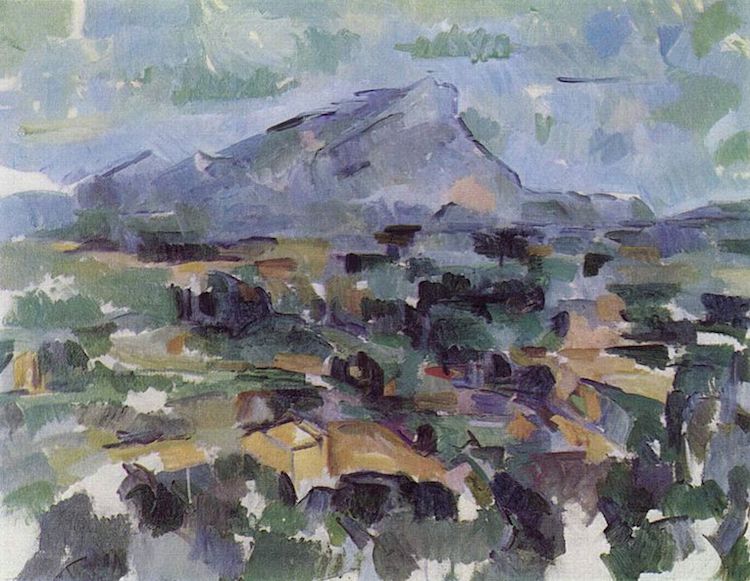

Art Movements That Influenced Cubism

Given the popularity of Post-Impressionism and Braque's own relationship with Fauvism, it is no surprise that both movements played a pivotal role in shaping Cubism.

Post-Impressionism

Cubists borrowed several artistic elements employed by Post-Impressionist painters—namely, Paul Cézanne.

These include flat planes of color, geometric forms, and, most significantly, a distorted sense of perspective. “The hard-and-fast rules of perspective which it succeeded in imposing on art were a ghastly mistake which it has taken four centuries to redress,” Braque explained to The Observer in 1957. “Cézanne, and after him Picasso and myself, can take a lot of credit for this. Scientific perspective forces the objects in a picture to disappear away from the beholder instead of bringing them within his reach as painting should.”

Paul Cézanne, “Mont Sainte-Victoire,” 1904–1906 (Photo: The Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

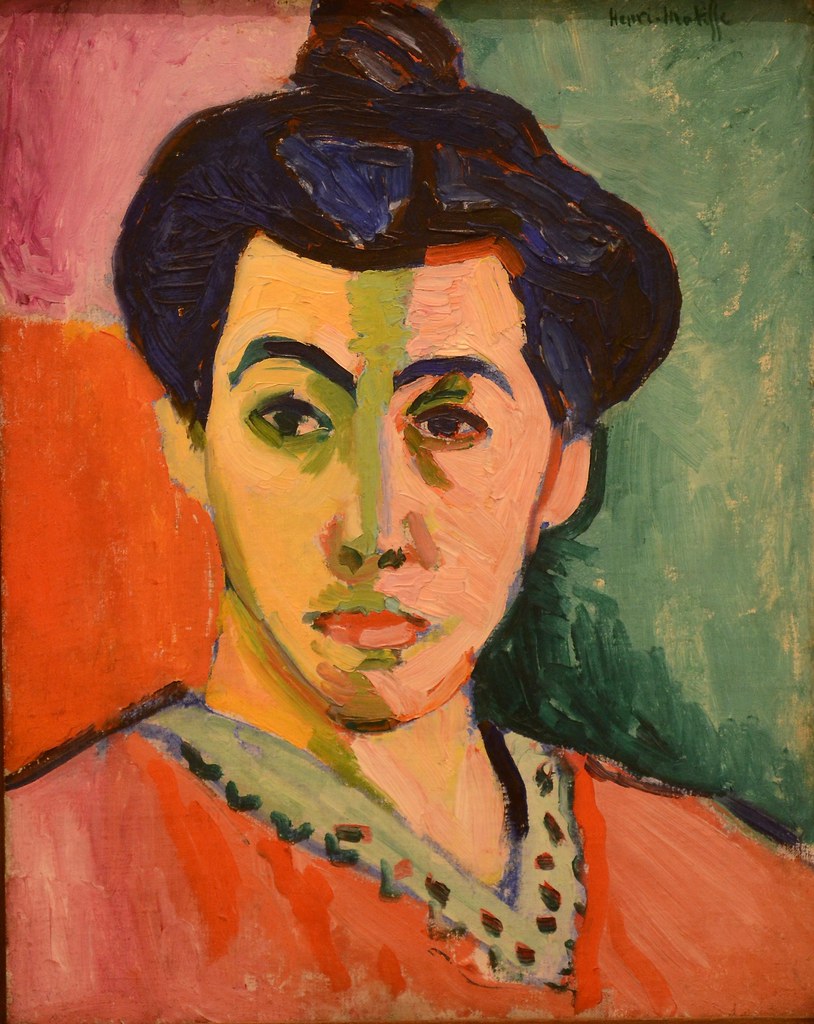

Fauvism

In addition to Post-Impressionism, Cubist art was inspired by Fauvism.

On top of Braque's association with the movement, this influence was strengthened by Picasso's relationship with Matisse, an artist renowned for using blocks of artificial color and repeating patterns to compose a scene. “You have got to be able to picture side by side everything Matisse and I were doing at that time,” Picasso recalled in the 1960s. “No one has ever looked at Matisse's painting more carefully than I; and no one has looked at mine more carefully than he.”

Legacy of Cubism

Like other modern art movements, Cubism would eventually influence—and even spawn—several other genres of art.

Futurists found inspiration in Cubism's energetic compositions, while Surrealists adopted and adapted collage art. Similarly, the idea of deconstructing subjects into fragments influenced artists associated with the Dada, De Stijl, Bauhaus, and Abstract Expressionist movements.

Marcel Duchamp (Dadaist), “Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2,” 1912 (Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to these modern genres, Cubism's influence is also evident in contemporary art. From Cubist tattoos to graffiti inspired by Picasso's portraits, these playful pieces showcase the timeless aesthetic, captivating compositions, and lasting legacy of Cubism.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Cubism?

Cubism is an art movement pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, characterized by fragmented subject matter deconstructed in such a way that it can be viewed from multiple angles simultaneously.

What are four characteristics of Cubism?

Cubist art features a single viewpoint, emphasis on overlapping geometric forms, fragmented subjects, and rejection of traditional techniques, such as modeling.

What are three different styles of Cubism?

There were three primary phases of Cubism: Proto-Cubism, Analytical Cubism, and Synthetic Cubism.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Iconic Artists Who Have Immortalized Themselves Through Famous Self-Portraits

You Can Now Explore Every MoMA Exhibit Since 1929 for Free Online

Stunningly Colorful Cubist Tattoos Inspired by Picasso

Simple Line Tattoos Inspired by Surreal Artists Like Picasso

![[ B ] Georges Braque - Passage à la Ciotat (1907) - Detail](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8243/8665407882_97fc52dec9_c.jpg)