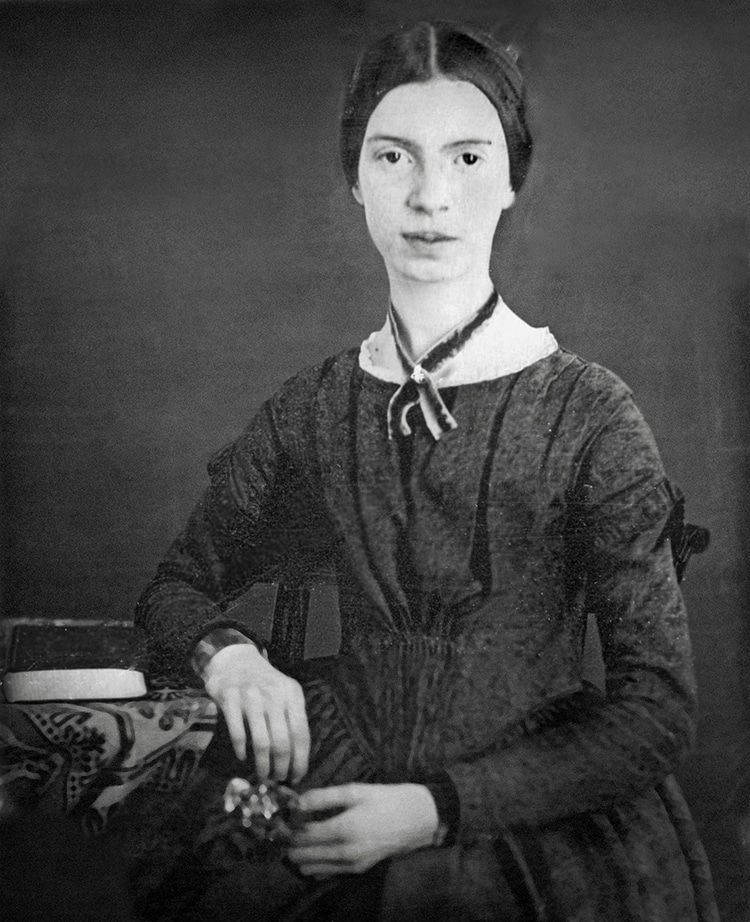

Digitally restored black and white daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson, c. early 1847. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

The now-renowned Emily Dickinson is widely regarded as one of the most important poets of American literature. Famously a recluse in her later years, the overwhelming majority of her poems were never published until after her death. Even then, it wasn't until the 1920s, 40 years after her death, that her unconventional style was embraced and celebrated as proto-modern work. Poetry wasn't her only passion, though. In fact, during her life, more of Dickinson's acquaintances would have known her as a gardener than a poet, according to scholar Judith Farr in The Gardens of Emily Dickinson. From a young age, she studied botany. While still a student, the avid anthophile compiled a remarkable herbarium, a compilation of dried plants.

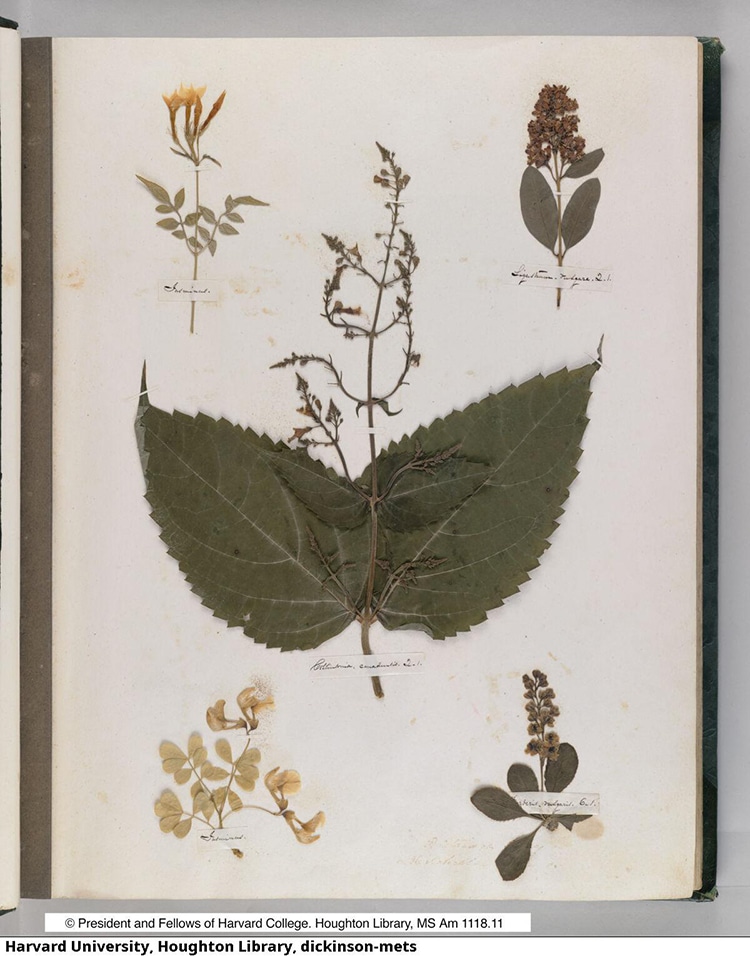

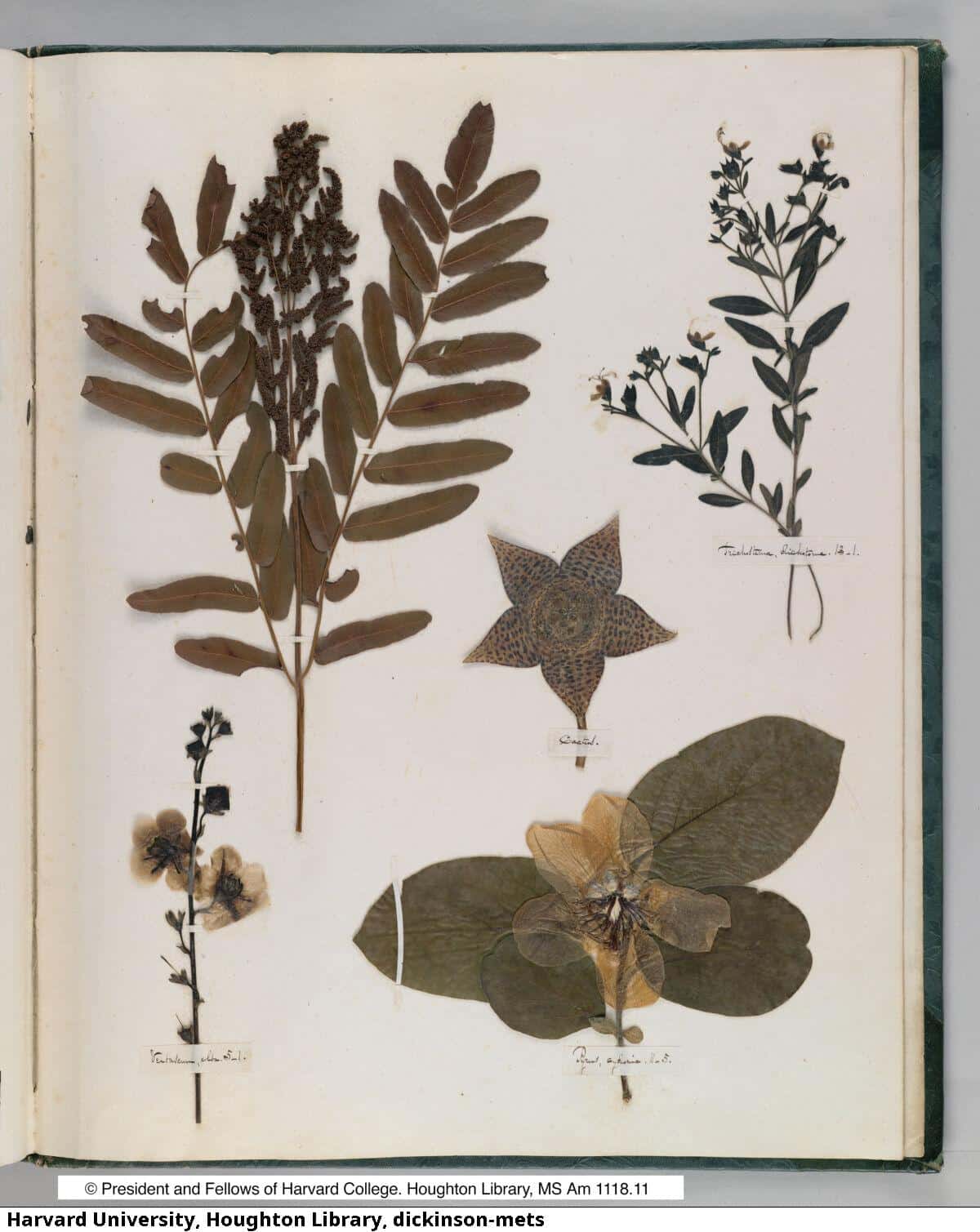

This herbarium still holds the same plants Dickinson dried 180 years ago and is held at Harvard University's Houghton Library. Unsurprisingly, though, the original herbarium is not available for viewing, even by academic researchers, since it is so fragile. Luckily, the Houghton Library used digital photography to make the collection viewable to scholars, and the general public. The book, housed in a green album embossed with a botanical pattern, contains 424 different plant specimens on 66 sheets of paper. Dickinson's neat handwriting can be viewed via the labels that use the scientific name of the plants.

Botany was a common past-time for girls of that era, an acceptable pathway to science through illustration, which was deemed to be suitably feminine. Over a third of Dickinson's poems refer to flowers, and she often gave gifts of her poems entwined with flowers to her friends and family. Farr argues that one can only understand Emily Dickinson the poet if one understands Emily Dickinson the gardener. For instance, most of the plants Dickinson features in her herbarium are ones native to her home in New England. Yet the collection opens with jasmine, a far more exotic species. Farr writes, “Just as her fondness for buttercups, clover, anemones, and gentians spoke of an attraction to the simple and commonplace, her taste for strange exotic blooms is that of one drawn to the unknown, the uncommon, the aesthetically venturesome.”

Emily Dickinson was a passionate gardener, creating her own herbarium when she was just 14 years old.

First page of Emily Dickinson's herbarium. (Photo: Houghton Library, Harvard University, Public domain)

Photo: Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)

During the Victorian Era, young women were often well-versed in the “language” of flowers.

Photo: Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)

Her herbarium was once inaccessible; but now, in Harvard's collections, it is fully digitized and viewable by the public.

Photo: Houghton Library, Harvard University (Public domain)

h/t: [Open Culture]

Related Articles:

Learn How to Create Botanical Art From Real Flowers in This Online Class

Meet the Talented Brontë Sisters: Charlotte, Emily, and Anne

Symbolism: A Meaningful Approach to Turn-Of-The-Century Poetry and Painting

8 Facts About Emily Dickinson, the Enigmatic 19th-Century American Poet