“The Oxbow (The Connecticut River near Northampton)” by Thomas Cole, 1836. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

During the 19th century, a group of American painters dedicated themselves to cultivating a style that would have its roots in the New World, rather than looking back to Europe. Inspired by the untamed landscape of their surroundings and filled with ideas of exploration, these landscape painters helped create what is now known as the Hudson River School.

In these landscapes, the environment is filled with drama and emotion. The wide, expansive spaces are dappled with warm color, as depictions of man are eschewed in favor of the terrain. From 1825 until its popularity began to decline around 1870, the group of artists associated with these heroic landscapes helped shape the way we view early America.

From the early work of British-born émigré Thomas Cole to the oil paintings of Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, these landscape paintings were often the first depictions of parts unknown. Whether they are views of Yosemite Valley and the American West to glimpses of South America, these paintings are the testimony of a critical time in American history and the development of native art culture.

“October in the Catskills” by Sanford Robinson Gifford, 1880. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Origins of the Hudson River School

The foundations of the Hudson River School can be found in the Romanticist painting that took hold in Europe at the end of the 18th century. The way that Romantic painters—particularly in England and Germany—embraced landscape painting on a grand scale was highly influential.

However, while some influence is based in Europe, the Hudson River School is a decidedly national style, coming at a time when American painters were looking to define art in their own country. For generations, artists had made a return to the Old World in order to study the Great Masters. But, increasingly, these artists wanted to cultivate a style that was uniquely American. This desire, coupled with this particular moment in history, made for the development of the Hudson River School.

In the mid-19th century, when the style really came into its own, America was coming out of the Civil War. Manifest Destiny, a popular philosophy that Americans were destined to expand west across North America, had taken hold. At the same time, industrialization was under way and rapidly transforming the country.

“Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California” by Albert Bierstadt, 1868. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Not only were artists more adventurous in leaving New York to explore parts unknown, but the resulting wild landscapes became a symbol for the unconquered continent. The love for untamed nature was something not typically seen in European landscapes, making the work decidedly American.

At the same time, these depictions of wide-open spaces, ready to be settled, gave hope to a population coming out of the war. Fresh and unspoiled, this new terrain was free from the scars of battle. As a whole, these paintings point to the spirit of adventure, freedom, and discovery that exemplified the nation during this critical time in history.

“View on the Catskill—Early Autumn” by Thomas Cole, 1836–37. (Photo: Public domain via Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Who named the Hudson River School?

The movement was given its name retrospectively, though there’s a debate on whether it was art critic Clarence Cook or artist Homer Dodge Martin who first used the term. Initially, it was a disparaging name, meant to trivialize the work of these artists who had fallen out of fashion in favor of the French Barbizon School.

While the name Hudson River School comes from the fact that early paintings depicted the Hudson River Valley and its surroundings, later work includes locations in the American West, New England, and even South America.

Thomas Cole, who is generally known as the father of the movement, spent a significant amount of time in the area after taking a steamboat up the Hudson in 1825. From there, he hiked the Catskills and the resulting paintings are the first landscapes of the area. Once Cole died in 1848, the mantel was taken up by a second generation of painters who expanded the locations of the landscapes.

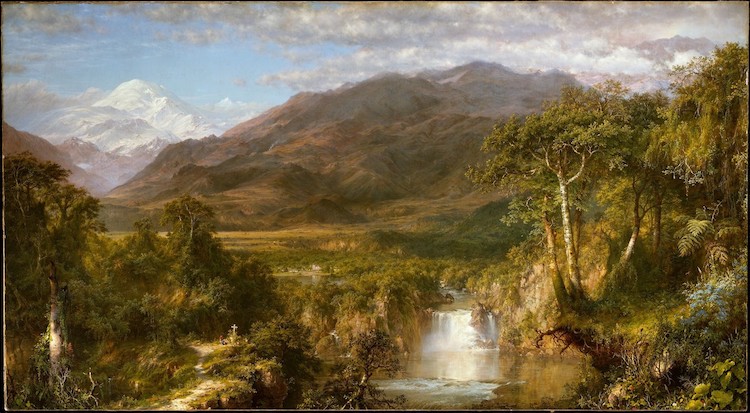

“Heart of the Andes” by Frederic Edwin Church, 1859. (Photo: Public domain via Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Frederic Edwin Church and the Second Generation

Moving into the second half of the 19th century, painters like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church were particularly sought after for their monumental landscapes. Both built on Cole’s principals—Church was his pupil—and depicted heroic landscapes that played on emotion and patriotism.

Church’s ten-foot-wide Heart of the Andes was a sensation from the moment it was painted in 1859. Based on the artist’s trip to Ecuador two years earlier, an estimated 12,000 to 13,000 people paid 25 cents apiece for the chance to admire it when it went on display in New York shortly after completion. Church played up the sense of drama by exhibiting the painting in a dark room with a single spotlight on the work. It later went on tour to eight American cities and London, where large crowds were drawn into the magnificent landscape. When it eventually sold for $10,000, it was the highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living American artist at the time.

Bierstadt, who was of German origin, is particularly known for his monumental paintings of the American West. Only Church rivaled him in fame and it's thanks to Bierstadt that we have early paintings of Yosemite. His presence was often requested by early explorers of the American West, who admired his technical prowess coupled with his subject matter. His series of paintings showing the Rocky Mountains were highly successful, as they allowed people who had not viewed these new areas of the United States to see more of their own country.

“Rocky Mountain Landscape” by Albert Bierstadt, 1870. (Photo: Public domain via White House)

Legacy of the Hudson River School

By the time the Centennial was celebrated in 1876, the Hudson River School's popularity was declining. Popular taste was turning toward France, where intimate landscapes were taking hold. Gone were the days where the monumental, larger-than-life paintings of Church and Bierstadt garnered crowds.

After World War I, the style saw a slight revival when the country was undergoing a period of extreme national pride. Today, the Hudson River School is recognized for its importance in developing a native art culture in America. The Hudson River Valley prides itself on being the home of this movement, and it's possible to visit Thomas Cole's home and hike the areas that inspired his evocative landscapes.

We also have several members of the school to thank for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Church, along with John Frederick Kensett and Sanford Robinson Gifford was among the founders of the museum. In fact, today there are a number of important works by these artists in the collection. Another important collection of paintings by Cole and Church can be found at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. As the painters were close friends with the museum's founder, nearly 25 of their paintings reside in the collection.

“Lake George” by John Frederick Kensett, 1869. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

“Niagara” by Frederic Edwin Church, 1857. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

“The Catskills” by Asher Brown Durand, 1859. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

“Looking Down Yosemite Valley” by Albert Bierstadt, 1865. (Photo: Public domain via Wikipedia)

Related Articles:

How the Groundbreaking Realism Movement Revolutionized Art History

Pre-Raphaelites: How a Secret Society of Artists Blossomed into an Art Movement

How Flowers Blossomed Into One of Art History’s Most Popular Subjects

Meet William Morris: The Most Celebrated Designer of the Arts & Crafts Movement