Discovery Mission 51A – Launch Complex 39A Remote Site 1 – 1984

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

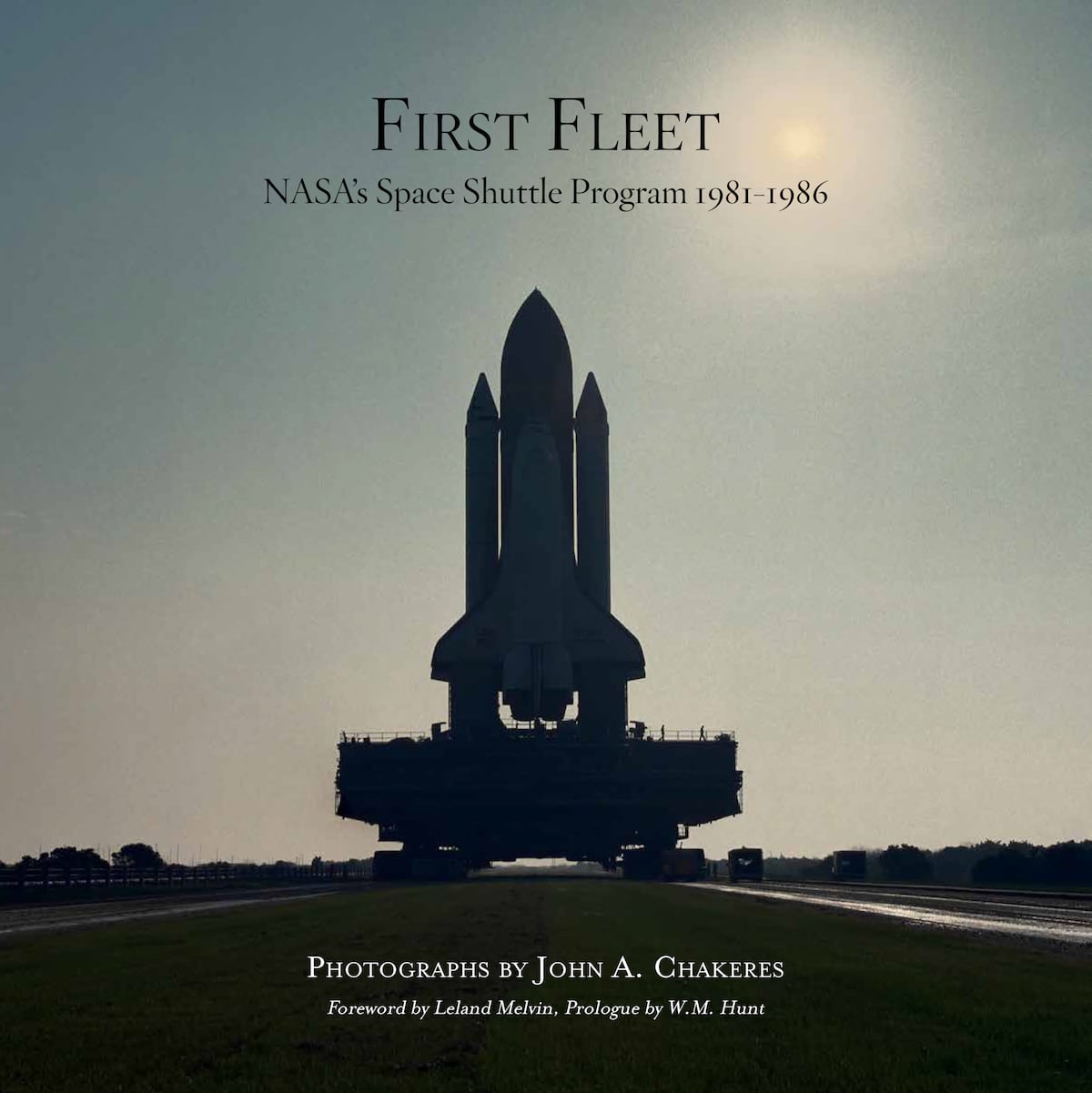

The career of photographer John A. Chakeres spans over 40 years. His work is included in the permanent collections of acclaimed institutions around the world. For his most recent publication, First Fleet (Daylight Books), he looks back at a project near and dear to his heart, one that saw him collaborating with NASA early in his career.

For nearly six years, Chakeres photographed the NASA Space Shuttle Program, capturing the magic and majesty of the missions that captivated the nation. As a young man, Chakeres was fascinated by space travel, which pushed him to ask NASA for permission to shoot launches at the Kennedy Space Center. By viewing his work through an artistic, not journalistic, lens, he aimed to capture a portrait of this special moment in time.

Chakeres' work came to an end in 1986, when the failed launch of the Challenger put a halt to the program for over three years. This tragic event, which resulted in the death of all seven crew members, created a deep wound for the photographer, so much so that all the negatives of his time at NASA went into a box. That lid remained closed for over 30 years.

Now, Chakeres is ready to share this historic moment in time with the public. First Fleet is an incredible publication that not only shows Chakeres' prowess as a photographer, but tells the narrative of the Space Shuttle program. From pre-flight to takeoff and landing, the photographs are a time capsule of this special moment in history.

“First Fleet captures the glory of the early flights of the Space Shuttle program,” writes Astronaut and S.T.E.A.M. Explorer Leland Melvin in the book's foreword. “Similar to the engineers who developed new procedures and systems to send humans to space in a reusable rocket turned glider, John developed ingenious systems and techniques to capture her magnificence on the pad, during launch, and returning back to Earth upon landing. This compilation of images inspires me to believe again in the power of people coming together to create things bigger than themselves to help advance our civilization.”

We had a chance to speak with Chakeres about his fascinating journey with the Space Shuttle program and how he looks back on his time with NASA. Read on for our exclusive interview and pick up First Fleet for an insider's look at this important time in space travel.

Discovery – Sunset Launch Complex 39A -1984

What are your first memories of NASA and the space program?

My first memories of NASA's space program were sitting in my third-grade class watching Alan Shepard go into space. It was on a small black and white TV set our teacher brought into class. I was mesmerized, and from that day forward I became fascinated with human space travel.

Challenger Mission 41B – Mosquito Lagoon – 1984

How did space travel influence your choice to work in photography?

I talked my mother into letting me stay home from school during manned space launches. In the early days of manned spaceflight, TV coverage was all day long. I began setting my father's Rolleiflex camera in front of the TV set and took pictures of the launches. That's what began my lifelong interest in photography.

Discovery Mission 51A – Climb Out Press Site – 1984

What sparked to you to write NASA and propose your services?

I had finished college in 1975 with an art degree in photography. I never lost my interest in space travel and followed every launch until the Apollo program came to an end in 1975. When NASA announced the Space Shuttle would fly in 1981, I saw an opportunity for a photo project.

At the encouragement of my wife, I sent a letter to NASA proposing the project and they granted me press credentials. When I sent the letter, I thought for sure they wouldn't approve my request. My proposal was a long-term art project rather than a photojournalistic project. So, when I got approved to photograph the launches I was elated and excited to begin the project.

Discovery Mission 41D – Launch Sequence – 1984

How did you prepare yourself to start the project?

As for preparing for the project, I didn't have any idea what to expect when I got to the space center. Up until this project, I was a large format view camera photographer. For the first launch, I brought every camera I had and decided I would figure out what worked best when I got there. It turned out my medium format Hasselblad was the best camera for what I wanted to shoot.

The first couple of launches I didn't get any usable pictures—the scale and scope of what I was doing were beyond anything I had ever done in photography. I basically had to reinvent myself as a photographer. By the third and fourth launches, I started to get pictures I thought were interesting.

Challenger – Shuttle Mate-Demate Device – Kennedy Space Center – 1984

Describe your first day walking into NASA. What do you remember most during that time?

Not knowing what to expect, I decided I would arrive in Florida a week before the launch. I loaded up all my camera equipment in my Landcruiser and left Ohio headed to Florida. I slept in the Landcruiser on the way down and figured I would find a motel once I got there. The day I arrived at the press center was anticlimactic. I expected to see hundreds of people and when I arrived, the parking lot was empty. I walked into the press center and it was empty.

Someone walked up to me and asked if they could help me. I said I'm here for the launch and they said the launch is in a week and come back then. I asked where everyone was and they said the press will begin showing up a couple days before the launch. I found a motel in Titusville, Florida and returned a few days before the launch. On my return, the parking lot was almost full and I had to hunt for a parking spot. I walked into the press center and it was filled with reporters and news crews filing stories and doing interviews. It was all very exciting for me to see behind the scenes of the news organizations covering the shuttle launches. I had watched many of the same reporters for years on TV and now I was there.

Discovery Mission 51G – Launch Sunrise Lagoon – 1985

Over your time with NASA, how did your approach as a photographer grow or develop?

My approach to photography was always from a fine art standpoint. With this project, my idea was to do a portrait of the Space Shuttle and its technology. I wanted to make the most monumental and majestic photographs I could. At first, the NASA press officials didn't understand what I was trying to do and didn't know what to do with me. They were used to dealing with photojournalists, who had very different objectives than me.

So, the first few launches I didn't get much access to locations I wanted to photograph. I was an artist among hundreds of journalist and NASA's priority was to the mainstream media. Since I was not affiliated with any news organizations, my press credentials only allowed me to be at the press site, three and a half miles from the launch pad. But in time I gained their respect and understanding and eventually got more access. At first, I thought I could get all my photographs in a couple launches, but as time went on I realized this project was bigger and more difficult than I had expected. The project ended up spanning nearly six years and 25 missions.

Challenger – Sunrise – 1985

Is there a particular image that you feel really captures your time at NASA?

The most iconic image I made is the cover photo of the book. The image is of the Space Shuttle Challenger at sunrise, as she made her way to the launch pad—a backlit picture with the very distinctive shape of the Space Shuttle stack in silhouette and the sun rising in the background. It's the one picture which captures my idea of a monumental and majestic image. It's a timeless image, a brief moment that tells a much bigger story. I think it is also a fitting memorial to the first crew and spacecraft lost in flight in NASA's space program.

Discovery Mission 51A – Launch Complex 39A Remote Site 2 Frame 18 – 1984

Obviously, it was a very difficult time for NASA, as well as the entire nation, after the Challenger accident. Once you left NASA, how did you move forward with your photography?

After the Challenger accident, it was a very difficult time for me emotionally. It took me nearly a year to get over the shock of what I had witnessed. My life as I knew it changed in a moment. It was as if someone had flipped a switch and from that point forward my life was forever changed. The shuttle program stood down for two years and my life as a photographer moved on to different projects.

Part of dealing with the loss of Challenger and my work I had done on the Space Shuttle program, was to preserve the negatives in archival storage boxes and set them aside in my studio. At the time, I had no idea I would never open the boxes again for nearly 25 years.

Challenger – Roll Over Head On View -1985

How did it feel to take the negatives out of storage and what has been the reaction?

The last Space Shuttle flight was in 2011 and I began thinking about the project again. At that time, I realized I had photographed a unique period in the history of NASA's space program. When I got the negatives out of storage and opened the boxes for the first time in 25 years, I didn't know what to expect. To my delight, all the negatives were in very good condition and I began scanning them and making prints.

In 2013, I was invited to Medellín, Colombia to participate in a photography festival. While I was there, I shared some of my Shuttle images with the other photographers who were also attending the festival. I got a very positive response to the images and they encouraged me to finish the project. So, as a result of attending the festival, I began work on the book project. Ever since I began the book project, I have gotten a lot of support and encouragement from my friends, family, and students.

Launch Complex 39A – Xenon Lights Press Site – 1985

Looking back now, how do you view your time at NASA?

I have often said I felt like I had a front row seat to the future as I watched the Space Shuttles rocket into space. As I look back on those days at the Kennedy Space Center, I realize I was very fortunate to have the opportunity, as an artist, to be able to dedicate the time to work on this project. It was that little kid in me who was fascinated by space travel that motivated me to continue working on this project over the years.

Discovery Mission 41G – Shoreline Cape Road – 1985

What do you hope people take away from the book?

I would hope people are reminded of the great things this country can do when we work together towards a common goal for the greater good. The Space Shuttle was the most complex vehicle ever assembled. It was the result of vision, desire, and the inherent trait of humankind to explore, discover, and work toward an understanding of the unknown. It is government agencies like NASA and programs like the Space Shuttle that truly make America great.