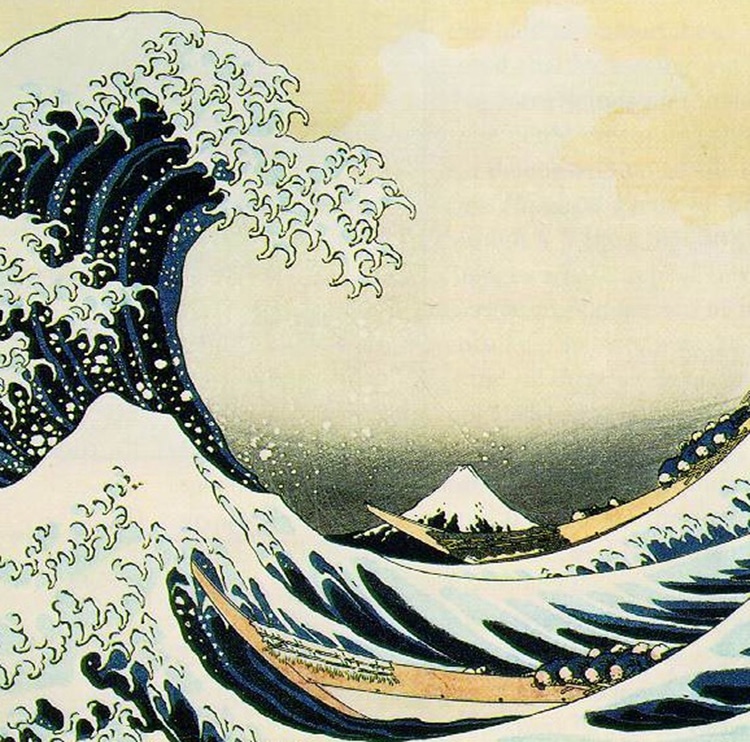

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Detail of “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

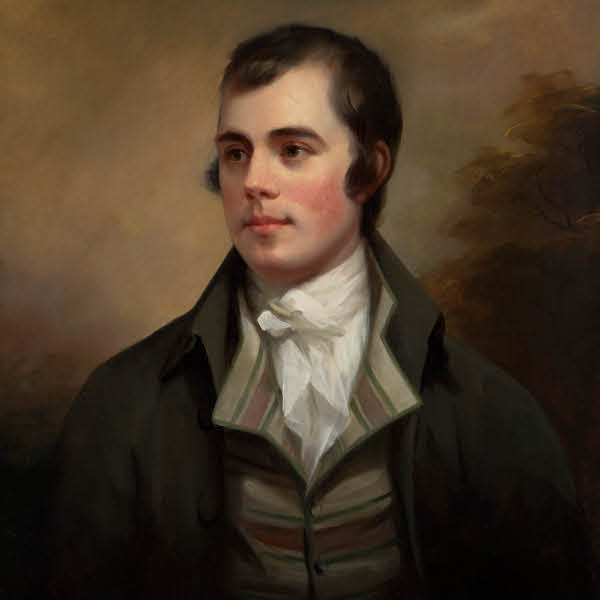

The instantly recognizable 19th century masterpiece titled The Great Wave off Kanagawa gracefully captures the power of the ocean in hues of Prussian blue—a pigment that previously had only been used by the richest of artists due to its rarity. Also known as The Great Wave, the print is not purely Japanese in style. Hokusai also studied European works and was particularly influenced by the linear perspective used in Dutch art.

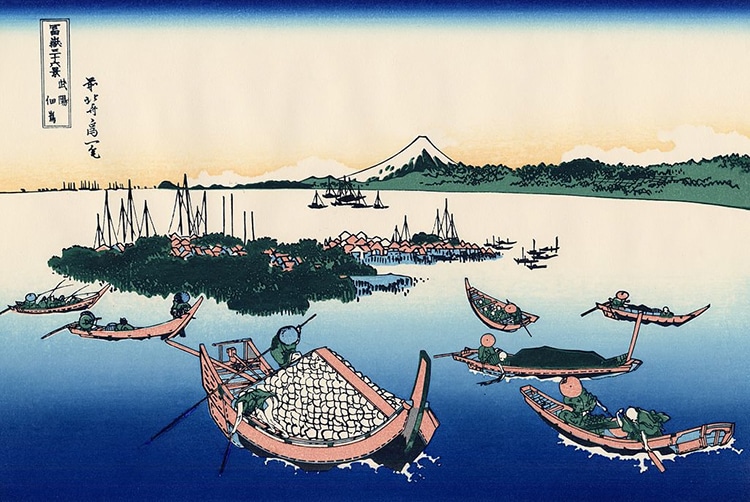

Although the eye may be drawn to the huge crashing wave, the most important subject is the small peak of Mount Fuji in the distance, which Hokusai painted over and over again in a series called Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. The woodblock prints, full of vibrant colors, depict Japan’s highest mountain from various viewpoints and environments.

Among the most famous is South Wind, Clear Sky (also known as Red Fuji) where Mount Fuji is seen close up, snow topped, and printed in a gradient of bright red. The 35th print, titled Ejiri in Suruga Province illustrates Japanese farmers struggling to battle extreme winds during winter, with Mount Fuji featured in the background, drawn with one simple line. Easily mass-produced, at first Hokusai sold them at cheap prices, but once tourism in Japan began to boom, the prints soared in price, and today, rare originals can cost thousands of dollars, depending on time of production.

“South Wind, Clear Sky” (also known as Red Fuji) from “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

“Ejiri in Suruga Province” from “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

“Yoshida at Tōkaidō” from “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

“Tsukuda Island in Musashi Province” from “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

Despite its popularity, the series was not considered to be “great art” by Japanese art historians at the time, who saw woodblock prints as a form of commercial printing, rather than a fine art form. However, today original prints of The Great Wave are treasured by many museums around the world, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the British Museum of London, the Art Institute of Chicago, LACMA of Los Angeles, and Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria.

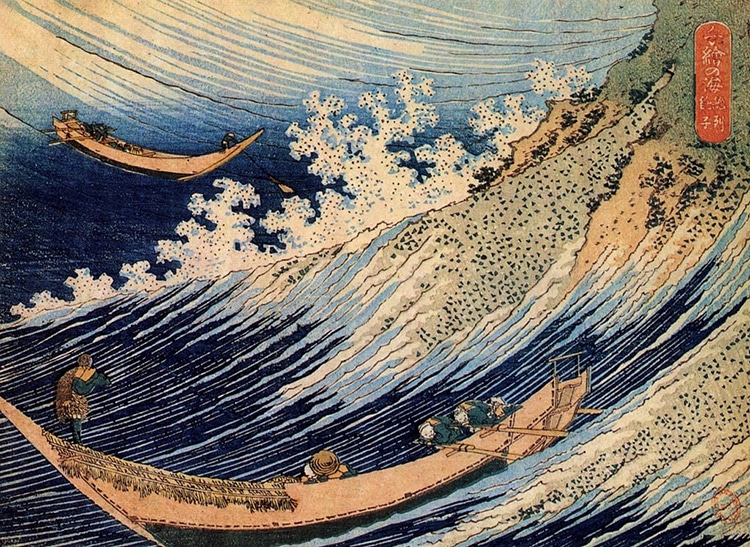

Other Series

Hokusai also created various other woodblock series such as One Thousand Images of the Sea (1832–34), also known as Oceans of Wisdom. The collection of ten prints feature scenes of fishermen working, and explore two of Hokusai’s favorite themes—hard work and the forces of nature. This is illustrated in Chōshi in Shimōsa Province, which shows fishing boats struggling in a stormy sea, echoing the scene of The Great Wave. In another series titled One Hundred Ghost Tales (1889-92), Hokusai illustrates Japan’s fascination with ghost stories.

“Chōshi in Shimosha” from “One Thousand Images of the Sea” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia

“Fishing by Torchlight in Kai Province” from “One Thousand Images of the Sea” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia

“The Ghost of Oiwa” from “One Hundred Ghost Tales” by Katsushika Hokusai via Wikimedia Commons

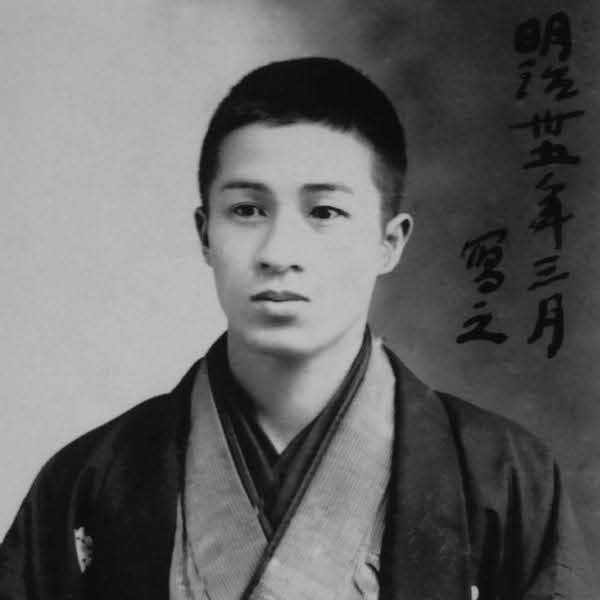

Believing that he would live to 110, Hokusai once said, “When I am 80 you will see real progress. At 90 I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At 100, I shall be a marvelous artist. At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. To all of you who are going to live as long as I do, I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age.” On his deathbed at age 90 (1849), he reportedly said, “If heaven had granted me five more years, I could have become a real painter.”

Although he didn’t make it to 110, many around the world believe Hokusai achieved the status of a master artist. Somewhat fittingly, his tombstone bears his final pseudonym, Gakyo Rojin Manji, which translates to “Old Man Mad about Painting.”

Related Articles:

The Unique History and Exquisite Aesthetic of Japan’s Ethereal Woodblock Prints

220,000+ Japanese Woodblock Prints Available Online in Growing Database

Library of Congress Makes Over 2,500 Japanese Woodblock Prints Digitally Accessible

How Japanese Art Influenced and Inspired European Impressionist Artists