Maurice Denis, “Poetic Arabesque,” 1892 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

Who were the Nabis?

Louis-Alfred Natanson, Photo of Ker-Xavier Roussel, Édouard Vuillard, Romain Coolus, and Felix Vallotton in 1899 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Symbolist poet Henri Cazalis christened the artists with the name “Nabis”—a term derived from the Hebrew and Arabic word for “prophets“—as a nod to the devout, nearly spiritual nature of their artistic brotherhood. “He gave us a name which, with respect to the studios, made us initiates,” member Maurice Debis explained, “a sort of secret society with mystical tendencies, habitually in a state of prophetic fervor.”

The Emergence of the Nabis

Paul Sérusier, “The Talisman,” 1888 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

The Talisman channels Gauguin's signature style: flat brushwork, expressive forms, and a vivid color palette. Most importantly, however, this groundbreaking piece illustrates the Nabis' idea of “pure painting,” a sensation-driven approach that would see the artists “liberated from all the yokes that the idea of copying brought to painters' instincts.”

Invigorated by this new approach to painting, the Nabi movement quickly materialized. The following year, the group held its first exhibition, The Impressionist and Synthesist Group, in the Café des Arts, an avant-garde locale within close proximity to the official art pavilion of the 1889 Paris World's Fair. In 1890, 18-year-old member Maurice Denis crafted The Definition of Neo-traditionalism, a group manifesto that famously prompted readers to “remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.”

That same year, the Nabis established a studio at 28 rue Pigalle in Paris. Though comically described as being “as large as a pocket handkerchief,” this site was key to the movement; in addition to serving as a place for the city's avant-garde to meet, mingle, and exchange ideas, it is where the Nabi movement developed and flourished.

Nabi Art

Édouard Vuillard, “The Flowered Dress,” 1891 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Still, Nabi pieces often exhibit aesthetic similarities. Following in Gauguin's footsteps, Nabi artists often employed painterly brushwork and expressive color. Like other artists of the time, they also evoked the look and feel of Japanese woodblock prints in their work, culminating in another key Navi characteristic: deliberately flat picture planes.

By forgoing an accurate sense of perspective, the Nabis were no longer limited to real-life spatial confines. “I'm trying to do what I have never done—give the impression one has on entering a room: one sees everything and at the same time nothing,” Bonnard said.

Édouard Vuillard, “Public Gardens,” 1894 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Folding screens were not the only decorative art objects crafted by the Nabis. They also produced wallpaper, tapestries, ceramic wares, and stained glass. In 1892, they also began designing avant-garde sets and costumes for theatrical productions—a working relationship that soon saw them creating posters, playbills, and other graphic art.

By the end of the decade, however, the Nabis had abandoned these cutting-edge art forms, returning to their devout painterly roots before disbanding in 1900.

Legacy

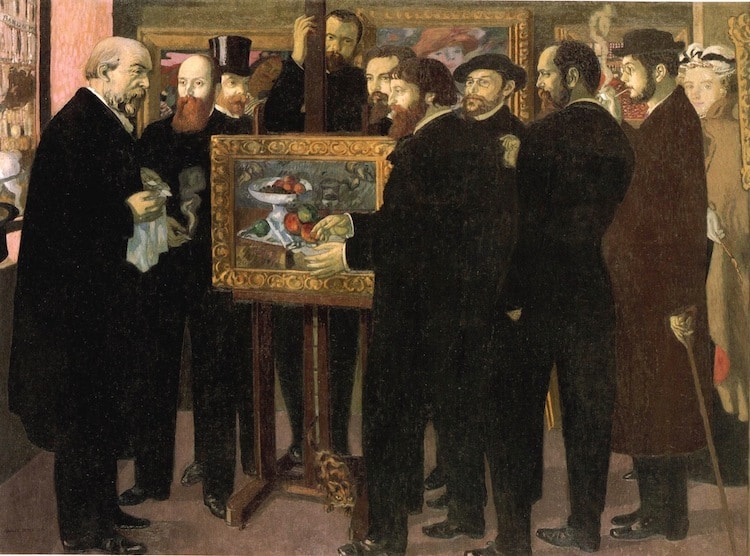

Maurice Denis, “Homage to Cézanne,” 1900 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

While the most prominent members of the Nabi group had moved on by the onset of the 20th century (Vuillard, for example, turned to realism, while Bonnard would explore a wide array of styles before his death in 1947), their legacy has remained relatively in-tact. Though often overshadowed by succeeding genres, Nabi art paved the way for modernists interested in a new form of traditional art—a paradox “prophesied” by Maurice Denis in his manifesto.

“Neo-traditionalism cannot waste its time on learned and feverish psychologies, literary sentimentality requiring an explanation of the subject matter, all those things which have nothing to do with its own emotional domain,” he said. “It has reached the stage at which definitive syntheses are possible. Everything is contained within the beauty of the work.”

Related Articles:

Exploring Fauvism’s Expressive and Colorful Contributions to Modern Art

The History of the Prestigious Paris Salon (And the Radical Artists Who Subverted It)

The Origins of Expressionism, an Evocative Movement Inspired by Emotional Experience

How Raoul Dufy’s Colorful Art Captured the “Joie de Vivre” of 20th-Century France