There are many movements that make up what we know today as “modern art.” In each case, artists sought to achieve a likeminded goal—regardless of their own style preferences. Impressionists, for example, reimagined ephemeral moments in time on canvas. Post-Impressionists explored the mind of the artists, while the Fauves took an expressive approach to art. And the Expressionists, a group of figures with eclectic artistic tastes, aimed to elicit emotion.

While the Expressionist movement started in Germany, it eventually spread all over the continent—and beyond. Here, we explore this evocative movement and the figures and groups that helped shape it.

What is Expressionism?

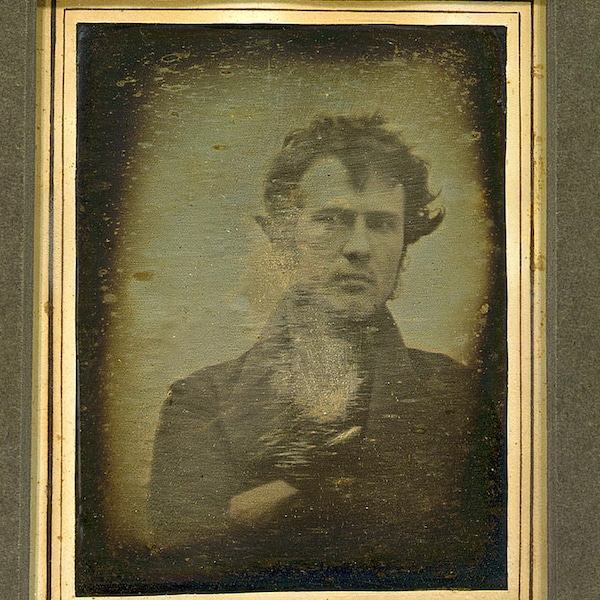

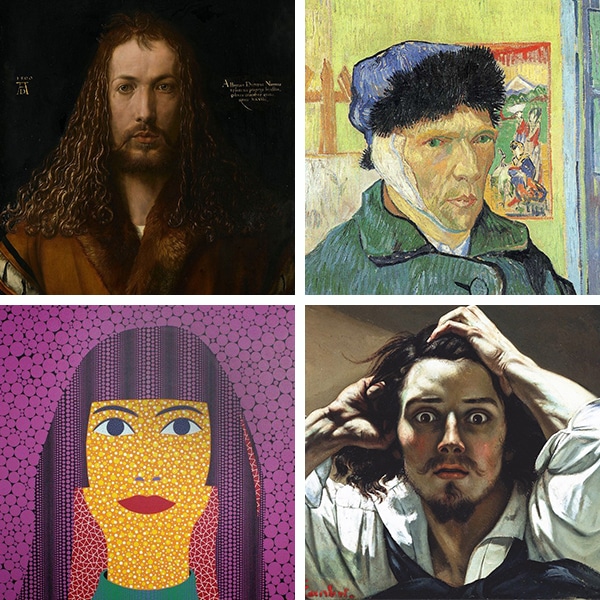

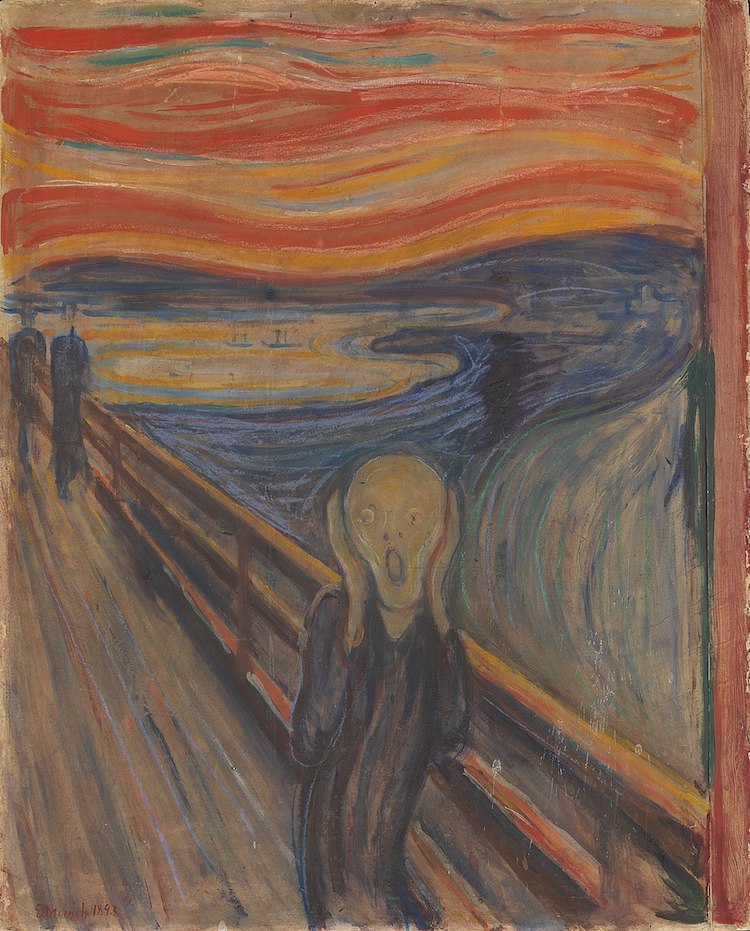

Edvard Munch, “The Scream,” 1893 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Expressionism is a modernist movement that emerged in early 20th-century Germany. Artists working in this style distort the reality of their subjects in order to “express” their own emotions, feelings, and ideas.

With an aesthetic and approach heavily inspired by the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch—two artists viewed as predominant precursors of the movement—Expressionists employed artificial color palettes, energetic brushstrokes, and exaggerated textures in their works. Together, these characteristics culminate in avant-garde paintings that favor the subjective over the true-to-life in order to reveal a glimpse into the psyche of artists.

History

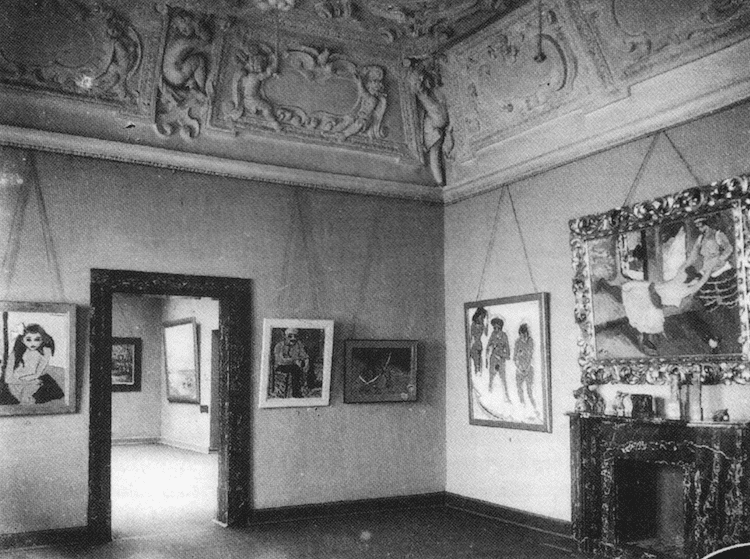

Exhibition of the german expressionist group “Die Brücke” in the Galerie Ernst Arnold in Dresden in September 1910 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Expressionism is believed to have made its debut in 1905. At this time, artists in Germany were responding to two important yet dissimilar phenomena: the prevalence and popularity of Impressionism and the seemingly chaotic state of the world in the years leading up to World War I.

Die Brücke

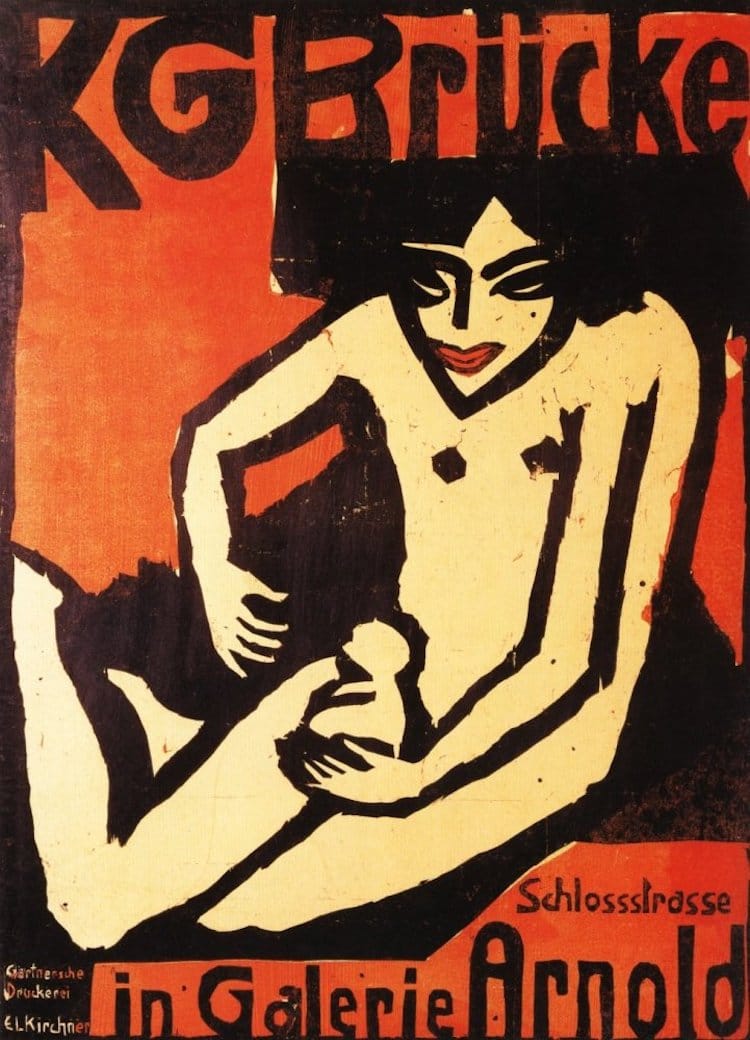

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Exhibition Poster, 1910 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

This dual interest inspired the formation of Die Brücke, or “The Bridge,” a group of artists whose name references a “youthful eagerness to cross into a new future.” Based in Dresden, Die Brücke was led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and co-founded by Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

A far cry from the Impressionists' focus on stylistic representation over emotional depth, members of Die Brücke sought to elicit a stirring response from the viewer through the use of primitive subjects, disconcerting colors, and distorted configurations. Though their approach was radical, they did seek inspiration in art of the past. Specifically, they emulated the work of Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer and Matthias Grünewald, whose woodcut prints inspired them to revive the printmaking practice and use the craft as a means to write their manifesto.

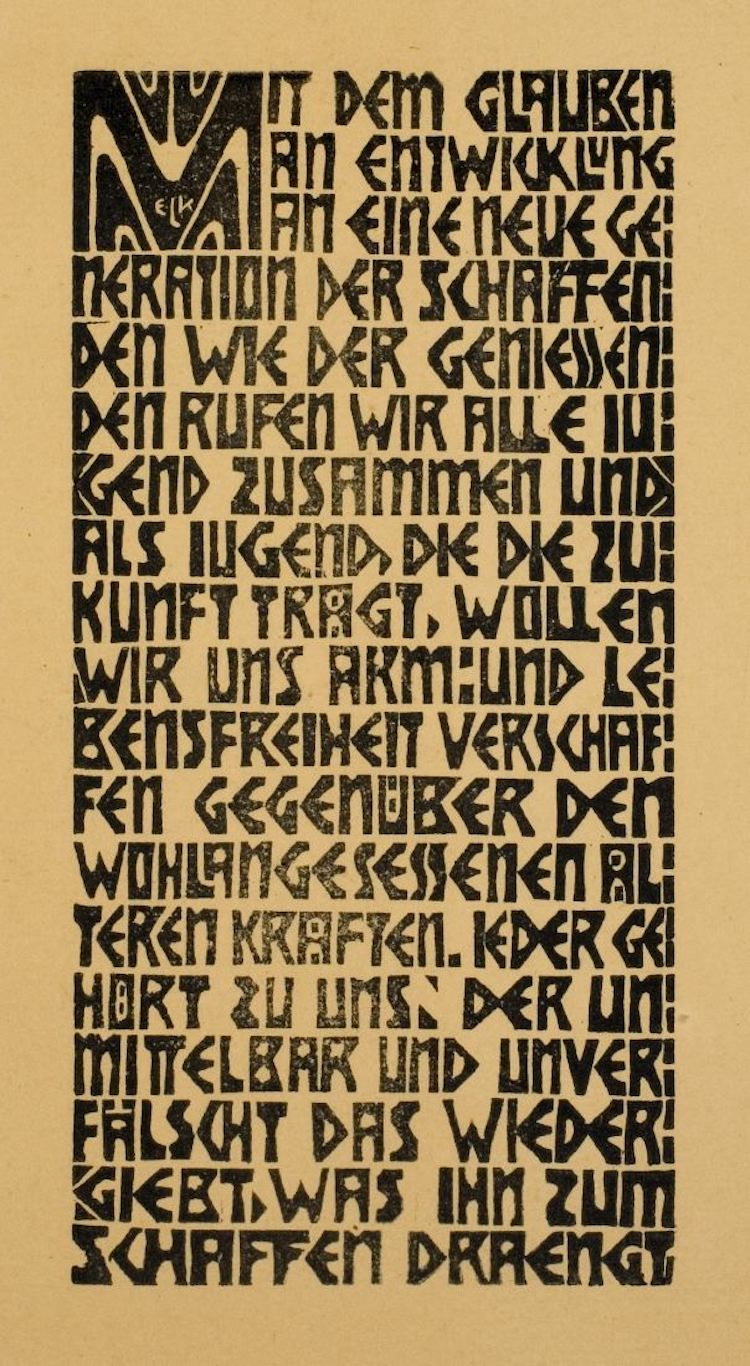

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1906 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Die Brücke continued to recruit new members in Dresden and other German cities for nearly a decade. In 1913, however, Kirchner published Chronik der Brücke, or “Chronicle of the Brücke.” Kirchner aimed to define and add structure to the movement with this written work, but his fellow group members viewed his interpretation as one-sided and decided to disband.

Der Blaue Reiter

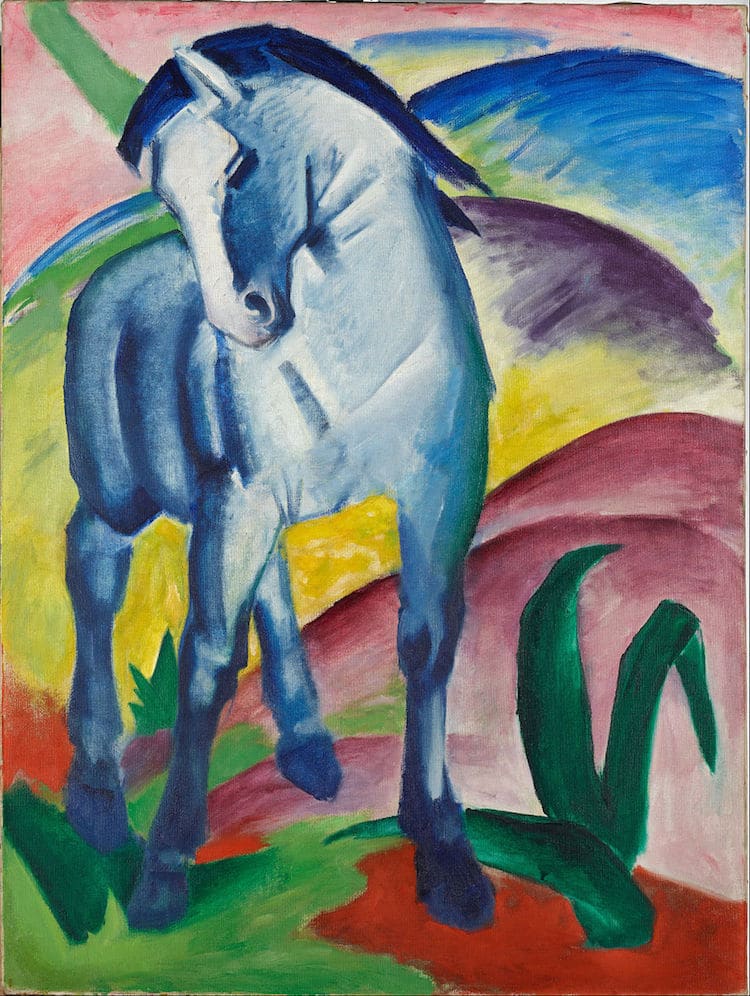

Franz Marc, “Blue Horse I,” 1911 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Just two years prior to Die Brücke's dissolution, Der Blaue Reiter (another Expressionist group) formed in Germany. With Munich as its home base, the group was made up of artists of Russian and German descent, with Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc among the most prominent.

The figures' artistic objectives varied. However, they were united by an interest in exploring spirituality and a belief that art is more than meets the eye.

To Der Blaue Reiter members, for example, colors were symbolic, and painting was intuitive. While they believed that these principles were hinted at in earlier art—including, most prominently, work from the Middle Ages—they interpreted it in an unprecedented, modernist way. As Franz Marc noted in 1912 (two years before his death and the end of the group): “Art today is moving in directions of which our forebears had no inkling.”

Wassily Kandinsky, “The Blue Rider,” 1903 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

For decades, “Der Blaue Reiter,” which translates to “The Blue Rider,” was believed to reference a painting created by Kandinsky in 1903. However, it seems this painting's title was given retroactively, leading art historians to believe another origin story: that it was simply inspired by a combination of Kandinsky's well-known penchant for the color blue and Marc's equestrian interests.

Influence

Though these groups were short lived, each one had a monumental influence on Expressionism—a movement that was not officially established until 1913. Expressionism continued to serve as the dominant artistic force in Germany following World War I. While its popularity faded around 1920, German artists revived it in the 1970s with the creation of Neo-Expressionism. Its popularity even spread to the United States, where it materialized as American Figurative Expressionism and, eventually, Abstract Expressionism.

In addition to inspiring Expressionist offshoots, the movement had a profound influence on contemporary art. Unlike most genres of art, Expressionism was not entirely discrete; not only did prominent Expressionist artists dabble in other styles, but the movement's effects touched several concurrent genres, including Futurism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Dadaism—a phenomenon that illustrates just how far-reaching the seemingly fleeting philosophies have been.

Related Articles:

25 Art History Terms to Help You Skillfully Describe a Work of Art

Exploring the Cutting-Edge History and Evolution of Collage Art

Bauhaus: How the Avant-Garde Movement Transformed Modern Art

Celebrate 100 Years of Bauhaus with These Free Online Documentaries

How to Make Your Own Woodblock Print Like the Japanese Masters