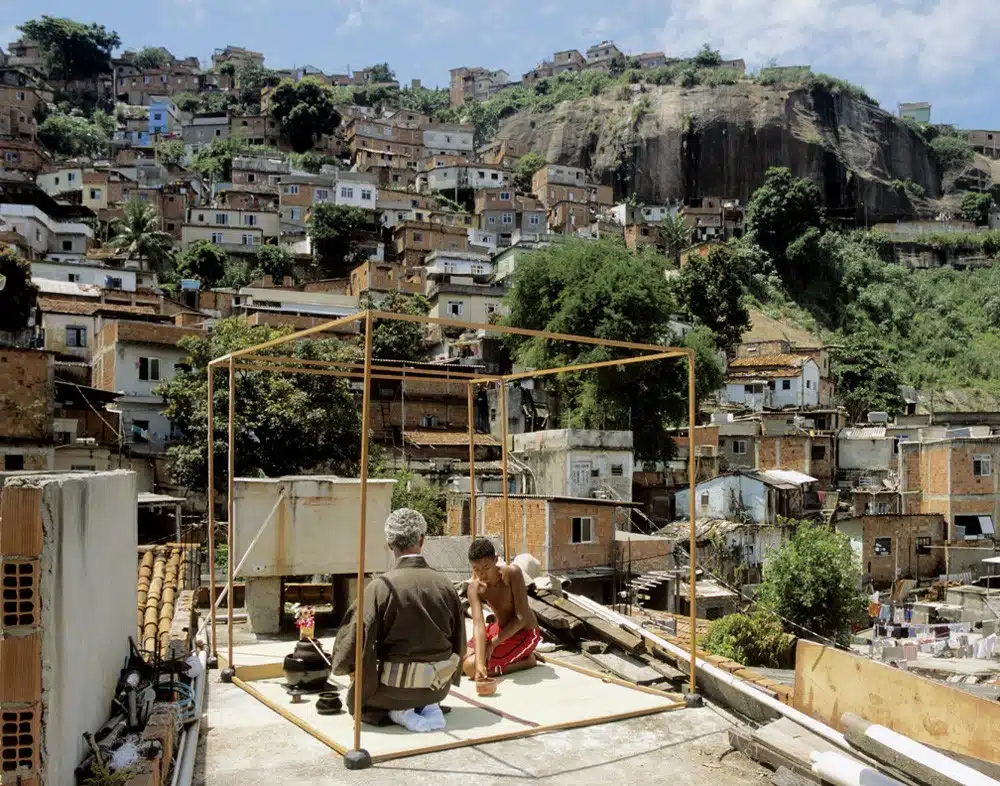

Denilson, Niteroi, Brazil © 2002 Pierre Sernet

In the early aughts, artist Pierre Sernet used the Japanese tea ceremony to unite cultures around the world in a powerful set of performances. Sernet's One series is often called Guerrilla Tea. The installation saw Sernet set up a “Tea Room,” denoted by a wood cube, in different global settings. He then sat and waited for a volunteer to participate in the ceremony and drink the cup of matcha that he prepared in front of them.

These spontaneous events were recorded on camera, with the photographs serving to immortalize these ephemeral one-on-one encounters. From remote villages in South Africa and the favelas of Rio to the bustling streets of New York City, Sernet's journey brought him to over 30 countries where he was able to engage with hundreds of guests.

In doing so, he forged meaningful human connections away from the modern trappings of technology. For Sernet, who was born in France, lived for many years in the United States, and now resides in Japan, One is a poignant reminder that humankind is more similar than different.

My Modern Met had a chance to speak with Sernet about this incredible artwork, which still strongly resonates today. Read on for our interview, where we discuss the impetus for Guerrilla Tea and some of Sernet's most meaningful encounters along the way.

Kheth and Mayndevi, Jaisalmer, India © 2005

What sparked the concept for your One series, which is often referred to as Guerrilla Tea?

At the start of the millennium, I perceived a growing polarization through the spreading of violent anonymous postings on the internet.

After the 9/11 Twin Towers bombing in New York, that trend only got worse as we saw the United States using 9/11 as an excuse, trying to impose its single-minded views on the rest of the world in a way that was detrimental and counterproductive to the influence it had exerted in the preceding 100 years.

This culminated with the trumped-up justifications for the invasion of Iraq, the advocating of torture as acceptable, and the condemning of any dissenting views.

You may remember the comparing of America’s then values, as those of “the new world,” as opposed to Europe’s “old-world values,” the so-called “outdated ones.”

Although I was born and grew up in France, I spent most of my working life in New York and felt America was losing its way. Freedom of speech and dissent without fear are the cornerstones of American democracy.

Freedom of speech was not meant by the founding fathers as giving permission to spew hatred-filled comments online while hiding behind anonymous postings or pseudonyms like “pink elephant.”

At that time, there was little I could do to change that, but I felt I could at least use artwork to address what I saw as the total lack of respect for other people, cultures, and lifestyles.

That is when I launched the One series, referred to as Guerrilla Tea by Japan's largest newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun, in their January 1, 2003 Art Section. I ultimately went on to do five other series about Faces, Love, Death, Nationality, and Sex, all intended to show the commonality of mankind throughout place and time.

Shinya, Rockefeller Center, NY, ©2001

Sandra and Laura, Barra Beach, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, © 2002

What was it about the Japanese tea ceremony that seemed like an effective way to unite people?

Because the tea ceremony is unique and unknown, I felt people would stop, pay attention, and wonder what the message could be when shown the works.

Tea ceremony is based on four concepts: harmony, purity, tranquility, and respect. These are values I feel strongly about, so you could say they are also my values.

The idea was to play on the juxtaposition of out-of-context and apparently incompatible cultures or environments in which I would be making tea and sharing my own values.

With the cube being used as a conceptual space, I wanted to invite viewers looking at my artworks, and to place their own set of cultural, spiritual, religious, or philosophical values within it.

Dinh, Halong Bay, Vietnam, © 2006

(continued) The purpose is to have the public see each of these spaces in a new and unique way, showing that these seemingly incompatible worlds and cultures are, in fact, based on similar universal values that can cohabit together.

I have shared a bowl of tea in over 30 countries, with hundreds of guests, with people of all sorts of social, religious, or ethnic backgrounds; each volunteered or was selected at random to participate in whatever setting the Tea Cube was placed.

That ranged from Halong Bay in Vietnam to villages in the Thar desert in India, to beaches like Rio de Janeiro’s Barra beach to Fifth Avenue in New York, among the more than 100 locations worldwide.

The vast majority had never heard of the Japanese tea ceremony—many had never even drunk tea before. Yet, they accepted the invitation to share a bowl of tea, sometimes a bit uneasy, but always with a smile.

Having said that, it has strengthened my belief in “respect.” It is what I think our contemporary world has lost most. I live in Japan as “respect” is the basis of its society.

Shinya, Times Square, NY, ©2001

Where was the first place that you staged a One event, and what was the reaction?

It was in March 2003 at Sonnabend Gallery in New York where I shared a bowl of tea with gallery collectors and visitors. However, the first outdoor events were for a video I had been asked to create for the April 2003 Asia Society Museum show in New York. The theme was the New Way of the Japanese Tea ceremony.

I created a video called T³ in which I made and served a bowl of tea, starting on a spring morning under Central Park's cherry blossoms, going through the days and the seasons, and completing the tea ceremony at dusk in the middle of Times Square.

New Yorkers, being New Yorkers, they are not fazed by much, and while we always had many people stopping to look, most surprised seemed to be the tourists. An amusing event did occur while making tea inside Grand Central Station.

During the process of purifying tea implements, the host uses a recipient, called a Kensui, placed at his left on the tatami mat, in which he disposes the water used while cleaning the bowl. When I finished pouring the used water into it and started whisking the tea, I noticed that a small basset hound dog was happily drinking out of the Kensui, probably a first for any tea event.

Maite, Piazza della Vittoria, Pavia, Italy © 2002

Alice, CDG, Airport, Paris, © 2002

What was the most powerful experience you had during the staging of Guerrilla Tea?

Tea events and guests are unique based on the location, individual, and character, and so there were many amazing encounters, some surprising, some funny, some peaceful, and some less so.

After all, these are “Guerrilla Teas,” and most often, we do not have any pre-advanced permissions to set up our “Tea Room Space” and make tea.

While in an old Pavia city square in Italy, I made tea, and although these are abbreviated ceremonies, it still takes about 30 to 40 minutes to serve a guest. The amazing part was that during the entire tea event, two Italian children, probably 8 and 10 years old, stood to my left, completely still and quiet as if mesmerized by the ceremony. They only left after the guest did.

At Paris’ Charles De Gaulle airport, I was making tea for an airport employee in the middle of Terminal 2 under the watchful eye of two well-armed CRS French military police officers. Suddenly, many came rushing into the terminal, ordering everyone to leave due to a bomb threat.

I turned to my guest and apologized that we would not be able to finish sharing our bowl of tea.

The CRS officer heard me and said, “No, you stay!” I retorted that we should leave, but he insisted we stay, and so we ended up being the only two people in the empty terminal, sharing a bowl of tea.

Cedric, The Bund, Shanghai, © 2005

Wan Chang, Jinshanling, China, © 2005

(continued) Another time, on the Bund in Shanghai, a large crowd had gathered while I started making tea. We had chosen a place we felt would be out of sight of the local police, as, after all, this was all happening in China without authorization. Shortly after we started shooting, we heard a car going up a ramp leading to where we were. It turned out to be a police car, and we were on the roof of their police station. I had changed into my kimono in the police station bathrooms.

The tourist police officer, called in to deal with foreigners like us, did not seem to feel that our tea values were at all compatible with his views of the enforcement of Chinese law and order. We spent the next four hours answering questions like, “Why tea?”

We had done a shoot that morning in the People’s Park with tai chi practitioners, before that on one of China’s booming construction sites and in other places in China, including on the Great Wall, but I suppose we had just been lucky up to that last one.

Demitris, Super Paradise, Mykonos, Greece, © 2003

Phwayinkosi, Zululand, South Africa, © 2008

(continued) However, whether on gay beaches in Mykonos, with Zulu people in their kraals in South Africa, with the Padaung people in Mae Hong Son [Myanmar], Thailand, or in India’s Thar desert with camel herders, most tea encounters show that despite being apparently different in our beliefs and lifestyles, we can still share a moment in time together and that despite our differing environments, we are far more alike than it may appear.

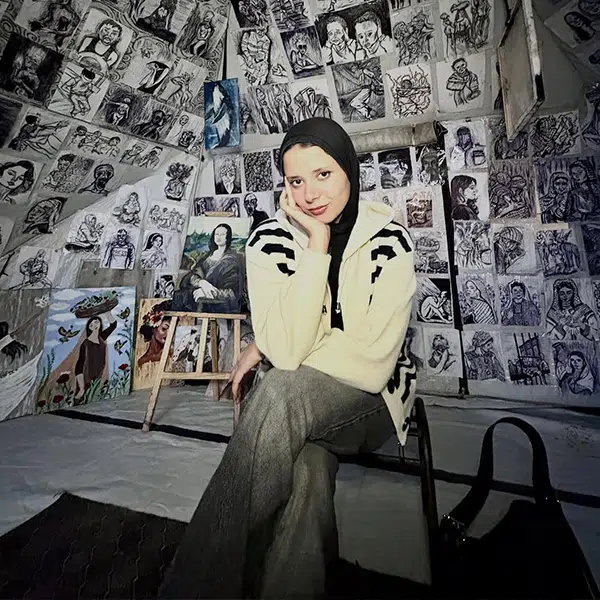

Making tea in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro was also an experience. After climbing through several homes, we reached a terrace where I could set up my tea room and install our large camera and equipment to shoot.

While I have photographed many guests, one has always stayed in my mind as one of the most “tea-like” people I ever shot anywhere in the world. He was David, a 14-year-old young boy for whom I made tea that day; he was more centered and focused than many of the professional tea people I met.

Although he probably had never heard of, nor may ever again drink a bowl of matcha, he truly felt like a chajin, a tea person. I felt that we shared a special moment in time in that unique setting.

David, Providencia Favella, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, © 2002

Fu Lai, Guangxi, China © 2005

Has anyone ever refused to participate or had a different reaction than you expected?

Refused, not really, but there were different situations where we encountered unexpected reactions.

In Guilin, China, we found a very rural village and started to set up our Tea House structure to shoot what really looked like a beautiful medieval Chinese village. The setting was spectacular with old stone houses and overhanging traditional eaves, and a light mist making it seem mysterious as well.

Unfortunately, a woman, whose house was not even in the picture we planned to shoot, wanted to be paid off. Our driver and translator probably spoke to her a bit harshly, and she drew in other villagers who started blocking anything we were doing, so we decided to leave to avoid further issues. It's one of the shots I regret most.

Later on that day, we shot a farmer with his buffaloes and the famed Guilin rock formations in the background.

Ironically, although the Japanese Tea Ceremony has its roots in China, and tea is a national drink, the only place in the world where I had to taste the tea I made before guests would drink it was China.

This happened several times, with my rural guests not trusting what I made despite them seeing it being made in front of them.

Another situation that happens a lot is that, when making tea in a crowded setting, no one wants to be first to sit with a strange foreigner wearing a kimono. It can take time to get a guest to participate.

Oscar, Capri, Italy, © 2003

Watanabe San, Saiko, Japan , © 2003

(continued) This happened, for example, in Capri, Italy, in the town’s small square where, after much negotiation with the mayor and the chief of police, I was given a one-hour window to shoot. After 50 minutes, I still had not been able to get anyone to sit. Luckily, a paparazzo photographer came by and started telling me that he used the same camera. After a few minutes, he agreed to sit for a bowl of tea and picture. After that, as usual, everyone wanted to share a bowl of tea.

In Japan, where everyone knows about tea, the issue is a bit different; Japanese guests feel uncomfortable participating in what is a strictly defined set of procedures, with a foreign host. This happened at Saiko Lake, one of the lakes around Mount Fuji. We had been fortunate to find a perfect setting next to the water, and for once, Mount Fuji San was visible with a beautiful blue sky.

The problem was that absolutely no one my wife asked wanted to share a bowl of tea with me until, luckily, a grandmother who lived in the farming village nearby came by. She had no problem receiving a bowl of tea. She had the right attitude: who cares if you know how to receive the tea or not? The spirit is far more important.

We got a shot with her carrying her baby grandson on her back, and it is one of my favorites. Minutes after we took the picture, Mount Fuji disappeared.

FungLien, Longsheng, China, © 2005

Daniel & Silvie, Palais de Tokyo Museum, Paris, © 2005

How have you seen the interactions between you and your guests change since you first began One?

On the guest side, since these are all independent tea ceremonies, it really depends on what the guests bring to the event. Some are clearly interested, often focused, or asking questions and wanting to really experience that moment.

In other cases, they have little interest, just participating without really being there. Quickly, I can get a sense of whether they have any interest or not. Their honest participation is also helpful for me in getting the right shot.

On my side, having traveled the world meeting with a wide range of guests, it has strengthened my belief that people, if left to their own feelings, are mostly ready to accept other cultures or values, especially once they understand them better.

I experienced very warm feelings shared by guests everywhere. One of the most memorable was after sharing a bowl of tea with the local tribespeople that live among the Longsheng Rice Terraces in the Dragon's Backbone Mountains of China.

While making tea there, we were hit by a sudden rain downpour, and we all got drenched. A group of older women invited us to their traditional homes with earthen floors; they served us rice stuffed inside bamboo, thrown directly into their earth’s flames to cook.

Kuo Chun, Construction Site, Shanghai, © 2005

Maplee, Padaung Tribe, Mae Hong Son, Thailand, © 2006

(continued) After a few hours, we left, and these women, no more than five feet tall, including their traditional costumes and headpieces, put their arms around our waists and gave us the biggest hugs imaginable.

The CEO of a large U.S. company, after sharing a bowl of tea on the ground floor of his Times Square headquarters, surrounded by large crowds, cameras, security people, and company employees milling around, was interviewed and said: “I have attended tea ceremonies before but this time I really felt we were just alone, the two of us.”

Although the portable “Tea Room” is only an open cube structure made of thin wooden struts, once a guest enters and really becomes involved, the tea becomes all-encompassing. In tea, this kind of feeling is often referred to as “entering the tea world.”

Another interesting reaction I encountered four or five times was with guests telling me that during our tea, they felt we were alone and that they were oblivious to the world around them. This happened in crowded museum events, like the Palais De Tokyo Museum in Paris, or among large groups of bystanders outside or in open areas with lots of traffic.

Jaswant, Osian, Rajasthan, India, ©2005

Xian Lin, People's Park, Shanghai, © 2005

What do you hope that people take away from One?

Japanese tea ceremony was strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism, where the concept of living in the now moment is fundamental. In tea, that is reflected in the saying “ichigo, ichie” which means “one time, one meeting,” coined by Ii Naosuke an influential 19th-century politician and tea man.

While in our lives we may meet with all sorts of people many times, each time we meet them is a unique occasion or moment in time.

One, the name of this series, refers to my one-time one-meeting with people from all around the world. Through the uniqueness of my tea encounters, I want to emphasize to viewers the importance of each moment we live in.

Most people do not think much about time, often forgetting how fleeting moments our lives are in terms of the Earth’s long history. I hope people also realize this by seeing my work, prompting them to live their lives in the now.

Also, as with my other series of works, I want to show the similarities that exist among the people of this world rather than their differences. I feel all of humankind shares the same aspirations and hopes. By showing in my works how similarly people look or deal with their environment, nationality, death, love, or sex, I hope viewers will become more open and accepting of other people's cultures and lifestyles.

Pierre Sernet: Website

All images © Pierre Sernet. My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Pierre Sernet.

Related Articles:

Performance Art Reveals the Passage of Time and Past Identity

Yoko Ono Invites Visitors To Participate in Immersive Exhibit at Tate Modern

Precarious Performance Art Turns Everyday Activities Into Awe-Inspiring Spectacles

Dance Duo Uses Powerful Shadow Performance Art To Shed Light to Sensitive Mental Health Topics