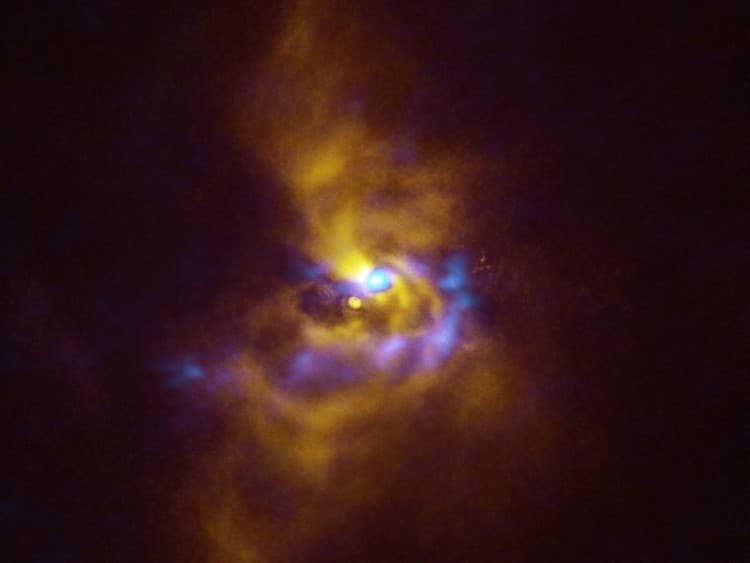

Photo: ESO/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Weber et al.

The European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) has just captured an image that will help scientists understand how giant planets are formed. By focusing on a young star 5,000 light-years away that has seen a marked increase in brightness over the past nine years, they were able to observe something extraordinary.

The star V960 Mon, which is located in the Monoceros constellation, grabbed the attention of astronomers because it brightened so dramatically over a short time. Shortly after the change, the VLT's Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument showed that material orbiting the young star had come together to form spiral arms that extend farther than the entire Solar System.

To get a closer look at what was going on, they used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which can peer into the dust. It was then that it became clear that the spiral arms were breaking into fragments and forming large clumps. This discovery is key because astronomers believe that one of two ways a giant planet can form is by “gravitational instability.” This occurs when large fragments of material around a star contract and collapse.

“No one had ever seen a real observation of gravitational instability happening at planetary scales—until now,” said Philipp Weber, a researcher at the University of Santiago, Chile, who led the study published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The sky around the location of the star V960 Mon. (Photo: ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgement: Davide De Martin)

In an image that combines the findings of SPHERE and ALMA, V960 Mon brightly shines in the center. A rust-colored spiral—imaged by SPHERE—swirls around the star. And scattered close to the center, the blue clumps of matter discovered by ALMA are also apparent. For scientists, it's thrilling to have visual proof of a long-held theory.

“This discovery is truly captivating as it marks the very first detection of clumps around a young star that have the potential to give rise to giant planets,” shared Alice Zurlo, a researcher at the Universidad Diego Portales, Chile, involved in the observations.

Once the ESO's Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is up and running, scientists will be able to observe the clumps in even greater detail. The telescope, currently under construction in Chile’s Atacama Desert, is set to be up and running in 2028.

Weber shares, “The ELT will enable the exploration of the chemical complexity surrounding these clumps, helping us find out more about the composition of the material from which potential planets are forming.”

ESO: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by the ESO.

Related Articles:

Astronomers Discover Surprising Rings Around Dwarf Planet Quaoar

James Webb Space Telescope Just Proved it Can Find Signs of Life on Other Planets

Scientists Find Distant Gas Clouds That Will Help Reveal How Our Universe Was Created