Photo: Stock Photos from MURAT CAN KIRMIZIGUL/Shutterstock

The lofty minarets of the Hagia Sophia stand over the skyline of Istanbul, Turkey. The magnificent stone basilica has been a fixture of the ancient city for 1,500 years—with frequent additions and renovations.

The spiritual structure has survived empires and transitioned religions. What began as an early Christian basilica eventually became a mosque, then a museum, and is now once more a mosque.

An architectural wonder, the Hagia Sophia (meaning “holy wisdom” in Greek) has a fascinating history and is a favorite attraction for tourists and the faithful. The building has seen crusades, world wars, and vast political shifts, but its legacy is central to both the history of Turkey and the world.

Read on for the history of the Hagia Sophia, a fascinating piece of sacred architecture.

Ancient Antecedents

A frieze with lambs from of the basilica built by Theodosius II in 415 CE. (Photo: Georges Jansoone JoJan via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

It is believed that a Roman pagan temple once stood where the modern building lies. Under the Roman Empire, the important ancient city on the Bosporus was known as Byzantium until the reign of Emperor Constantine I. The first Christian emperor, he moved his capitol from Rome to Byzantium in 324 CE. The city was then renamed Constantinople. This monumental shift in Roman religious policy and the geographic center of power established Constantinople as an important Christian site. The Bishop of Constantinople became second only to that of Rome in power and prestige.

The first Christian church on the site of the Hagia Sophia is thought to have been completed by Constantine's son the Emperor Constantius II in 360 CE, although its construction may have been ordered by Constantine himself upon his establishment in the new capitol. The Roman emperors who followed continued to make additions and repairs to what was called “the Great Church.” Excavated remains of the ancient church as it stood in the 5th-century shows complex stonework, including vaulted ceilings and friezes depicting early Christian symbolism. The ancient church was destroyed by fire in 532 CE during the Nika Revolt—a politically motivated violent rampage by upset citizens who took issue with many of the advisors and policies of Emperor Justinian I.

Under Control of Justinian the Great

A mosaic depicting Mary, the Christ Child, Emperor Justinian the Great, and Emperor Constantine I. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Among his major legacies is the present-day Hagia Sophia. After the Nika Revolt destroyed the Great Church, Justinian almost immediately ordered construction of a new one. Under the architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, a new building was swiftly constructed. The architects were mathematicians, and the church drew upon their knowledge of engineering and geometry. They created an enormous lofty stone dome supported by two flanking smaller semi-domes. The interior features three aisles and a second-floor gallery. The exterior was coated in thin slabs of white marble, while the interior is of polychrome marble in rich green, purple, and gray hues. The many columns which help support the building were imported from other buildings across the empire.

Despite the mathematic prowess of the designers, the new building could not support the weight of its own dome during two earthquakes in the 550s. A new ribbed dome was constructed which was actually taller but better supported by pendentives (corner supports in the square space underneath). The opulent interior of the church was decorated further by Justin II—Justinian's heir—who added gold mosaics. An “Imperial Door” was reserved for the emperor's personal use.

Over the almost 900 years the building remained in Byzantine hands, the successive emperors added new features to the church. Between the 10th and 12th centuries, many mosaics were added or altered. They depict figures such as the Byzantine Emperors, Constantine the Great (who received sainthood in the Eastern church), the Virgin Mary, and Christ. Other additions had pagan origins.

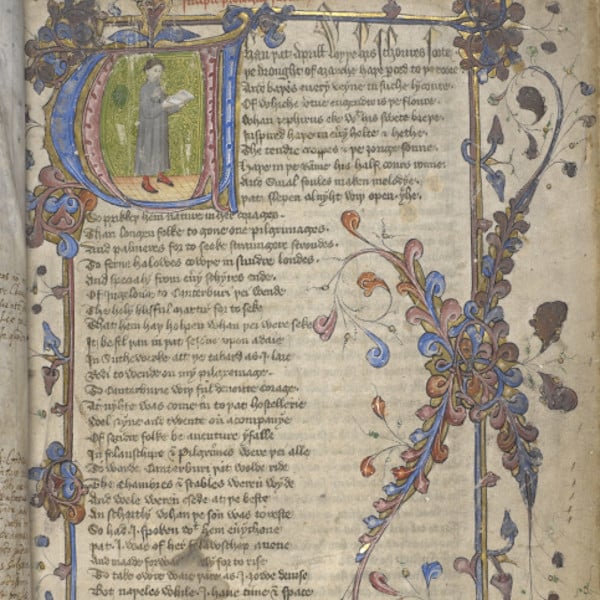

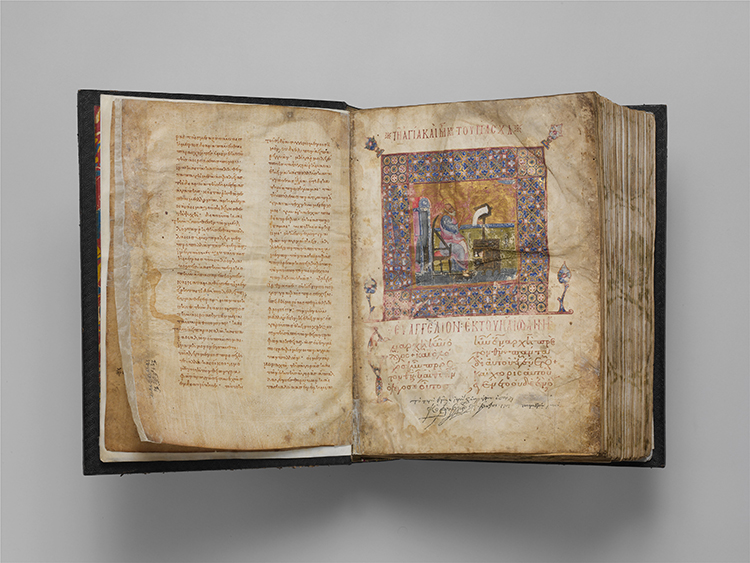

Jaharis Byzantine Lectionary, an illuminated manuscript in Greek likely created for the Hagia Sophia circa 1100. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art [Public domain])

After the split, the east was beset by Crusades ordered by the Roman Catholic Church. Although targeting the Muslim-occupied Holy Lands was the initial goal of the crusaders, by the fourth crusade the Catholic forces were targeting their Orthodox brethren. In 1204, the city of Constantinople was sacked, including the Hagia Sophia. The interior was desecrated; the empire would not gain control of the city back until 1261.

Claimed by Ottoman Rule

Hagia Sophia as a mosque with minarets in 1718. Engraving by Dutch artist and writer Adriaan Reland. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Taking its name from the leader Osman I, the Ottoman Empire pushed into the Balkans and steadily gained military might. Sultan Mehmed II captured Constantinople in 1453, effectively taking the last crown jewel of the old Byzantine Empire. During this conquest, the already old building was further damaged and looted. However, its beauty seemed to have struck the Sultan, who decided to convert the church to a mosque.

Religiously, this conversion meant a reading of the shahada (a declaration of faith) and the holding of Friday prayer at the Aya Sofya (Hagia Sophia in Turkish). Architecturally, the change in faiths dictated several new additions. A mihrab facing the direction of Mecca replaced the Christian altar, and a minbar (a pulpit with stairs for sermons) was also added. A minaret was also added, from which the call to prayer sounded.

Interior of the Hagia Sophia in an 1852 engraving by Gaspare Trajano Fossati. Hagia Sophia was a mosque in the Ottoman Empire's capital. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Becoming a Modern Museum

Interior of the Hagia Sophia, photographed in 2010 while the building was still a museum. (Photo: Stock Photos from VVOE/Shutterstock)

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire ceased to exist as a political entity, and the Republic of Turkey was officially recognized in 1923. Constantinople became the city of Istanbul. In 1934, under President Kemal Atatürk, the Hagia Sophia was secularized. The next year, the building was turned into a museum and the once-covered mosaics and original ancient floor were unearthed.

Throughout most of the 20th century, frequent repairs were necessary. Falling within the designated UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the “Historic Areas of Istanbul,” the building has been the object of frequent conservation. Now, over three million people a year visit the famous site.

Back to Worship Space

In July 2020, worshippers attend prayer outside the Hagia Sophia upon its reconversion to use as a mosque. (Photo: Stock Photos from MITREPHOTOGRAPHY/Shutterstock)

As a space held sacred to both Orthodox Christians and Muslims, many believers have a vested interest in the use of the Hagia Sophia as a place of worship. In the past ten years, calls to reconvert the secular building back into a mosque have grown.

In July of 2020, the museum was officially converted back into a mosque under the leadership of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The move has ignited much tension and controversy. Secular and religious factions within Turkey disagree over the decision, while representatives of the Orthodox faith around the world have expressed dismay. The change was made without consulting UNESCO, although Turkish authorities say the Christian symbols inside will not be altered and the Hagia Sophia will remain open to all.

Photo: Stock Photos from MURATTELLIOGLU/Shutterstock

The Hagia Sophia's return to being a place of worship is one more chapter in the long, captivating history of this sacred site; being at the center of national and geopolitical events is nothing new for this magnificent structure.

Related Articles:

Photos of Abandoned Churches Display the Decadent Beauty Left Behind in Ruins

Ancient Church Found Hidden Under the Waters of Lake Iznik

Beloved Stray Cat Given Memorial Service at Church She Called Home for 12 Years

Photographer Richard Silver on His Architectural Photography and Vertical Churches [Podcast]