View this post on Instagram

In the 1930s, American artist Alexander Calder kicked off a new kind of kinetic sculpture. Known as Mobiles, these pieces explore the capabilities of sculpted works by incorporating free movement—an element evident in both his standing object-mobiles and his hanging suspended mobiles.

While Calder's name is now synonymous with this type of art, his oeuvre is characterized by a range of creative projects, from an early circus-inspired series of sculptures to an aircraft he embellished in the 1970s. In this list of seven fascinating facts, we explore these pieces—and much more—in order to understand the significance of Calder's life and career.

Full Name | Alexander Calder |

Born | July 22, 1898 (Lawnton, Pennsylvania) |

Died | November 11, 1976 (New York City, New York) |

Notable Artwork | Mobiles |

Movement | Kinetic Art |

Here are 7 fascinating facts about the modern artist Alexander Calder.

His parents didn't want him to pursue art.

View this post on Instagram

As one of modern art‘s most influential figures, you may think that Calder's creativity was unconditionally fostered by his parents—especially since he was born into a family of artists. His portraitist mother and installation artist father, however, did not want their son to follow in their footsteps. Instead, they urged him to attend college, and, in 1921, Calder graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey.

However, while working as a mechanic on a ship the following year, a picture-picture scene inspired Calder to reconnect with his artistic roots. “It was early one morning on a calm sea, off Guatemala, when over my couch—a coil of rope—I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other,” he wrote in 1966. When the ship docked, he picked up some paints and brushes and moved to New York to pursue a career as an artist.

One of his most pivotal works was inspired by The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

While in New York, he studied at the Art Students League and worked as an illustrator for the National Police Gazette magazine. One of his assignments required him to attend the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Seeing and sketching this spectacle had a profound impact on Calder, culminating in a career-changing, circus-inspired series.

Cirque Calder, a whimsical model that features animals, clowns, and acrobats crafted out of wire, wood, string, metal, fabric, cork, and cloth, was the first of these works. Like a puppeteer, Calder would choreograph and perform the circus, which was accompanied by fanciful music and theatrical lighting.

The title of his most famous works is a pun in French.

View this post on Instagram

Following the success of Cirque Calder, the artist started to produce other works rooted in mechanics. In 1931, he began creating a collection of kinetic sculptures featuring distinct moveable parts. These unique creations were deemed “Mobiles” by Dada master Marcel Duchamp, who appreciated the fact that, in French, mobile means both “motion” and “motive.”

In their earliest phases, Calder's mobiles were controlled by motors. However, he eventually decided to forego this approach and instead created sculptures that relied on organic means—like air or touch—to move.

His abstract sculptures are inspired by forms and phenomena found in nature.

View this post on Instagram

Calder paired this newfound interest in natural movements with a fascination in natural shapes. According to the National Gallery of Art, “he usually cut natural forms that looked like leaves and petals rather than hardedge geometric shapes,” culminating in works aesthetically reminiscent of branches and blossoms.

Additionally, these works often accentuate the presence of the wind. “When Calder's mobiles move with the breeze, they change shape and cast interesting shadows,” the museum explains. “Some even ‘sing' as their movable parts rub against each other.” Together, these elements illustrate Calder's interest in emulating nature with his mobiles.

He also dabbled in painting, printmaking, jewelry crafting, and staging.

View this post on Instagram

Though known for his sculpture, Calder worked in a large range of mediums. As early as 1906, he was crafting jewelry—a body of work that would eventually total over 2,000 pieces. In the 1920s, he began producing paintings and prints. Like his sculptures, these works on paper often favored an abstract, geometric style. And, over the course his career, Calder created a handful of stage sets for theatrical shows, including avant-garde ballets and modernist dramas from the 1930s through the 1960s.

An airline commissioned him to decorate a jet.

View this post on Instagram

Calder's most colossal commission came later in his career. In 1973, Braniff International Airways asked the artist to decorate a full-sized Douglas DC-8 jet airliner in his distinctive style. Given his background in engineering and his interest in motion, Calder accepted the offer.

To prepare for this huge undertaking, “Calder created numerous fiberglass models, each painted with different colors and designs,” the Guggenheim explains. “Aspects from each model were then incorporated into the final painting on the plane, which bore Calder’s signature rather than the Braniff logo.” Known as Flying Colors, this plane took flight in 1973 and primarily serviced South America. Two years later, he designed another plane for the airline: Flying Colors of the United States.

In 1982, the airline went out of business. The first aircraft was sold to a leasing firm, while the second rendition was accidentally destroyed during filming for a movie.

In 1977, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously.

View this post on Instagram

In 1976, President Gerald Ford intended to award Calder with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The artist, however, refused this honor in order to protest the Vietnam War—a cause he also supported through politically-charged posters and prints.

However, following his sudden death that same year, Calder was awarded posthumously. Today, he is among nine artists who have received this honor, including Georgia O'Keeffe and Norman Rockwell.

Related Artists:

9 Abstract Artists Who Changed the Way We Look at Painting

6 of the Best Modern Art Museums in the World

The Surprisingly Heart-Wrenching History of Robert Indiana’s ‘Love’ Sculptures

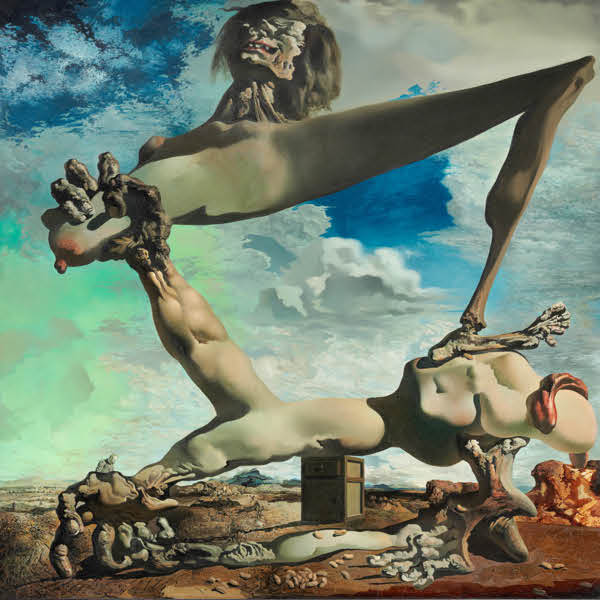

Exploring the Experimental and Avant-Garde Art of Surrealism