Cat Statuette intended to contain a mummified cat, Ptolemaic Period, 332–30 BCE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The ancient Egyptians' special love for cats is well known. In fact, cat lovers today have them to thank for introducing African wildcat DNA into domestication; this would eventually become the beloved tabby. But why did were Egyptians so enamored by these early felines?

Read on to discover the fascinating place of domestic cats in ancient Egyptian art, religion, and culture.

“Cosmetic Vessel in the Shape of a Cat,” Middle Kingdom, circa 1990–1900 BCE (Photo: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Domesticated Companions

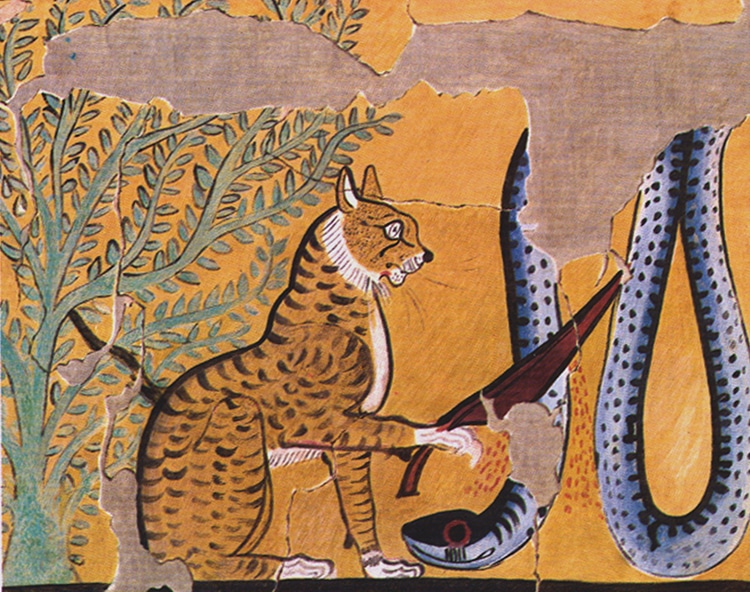

A scene in the tomb of Sennedjem (TT 1) in Deir el-Medina of western Thebes. In the Book of the Dead, a cat kills a snake, a function house cats performed in real life too.

“Cat Killing a Serpent,” facsimile from 1920–1921 by Charles K. Wilkinson; original from New Kingdom, circa 1295–1213 BCE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Wild cats appear to have become close to humans in Neolithic times in the Near East. As man gathered food, rodents followed. Cats, in turn, may have followed the rodents, living close to human communities. Scholars have analyzed the DNA of ancient cats and believe that around 1500 BCE African wildcat DNA merged with the cats of ancient Mesopotamia.

Unlike the dog, cats were not bred to perform tasks such as herding. Evolutionary geneticist Eva-Maria Geigl, who studied the DNA, half-joked to National Geographic, “I think that there was no need to subject cats to such a selection process since it was not necessary to change them… They were perfect as they were.”

Cats in Egyptian Culture

A cat eats fish under a table, 15th century BCE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Lions and African wildcats appear in the earliest Egyptian art. As of the mid-third millennium BCE, cats in collars were depicted in tombs. These paintings suggested pharaohs kept wildcats as pets. Pharaohs and nobles would long continue to be associated with these noble beasts. By the 20th century BCE, a breed of domestic cat was found depicted in tombs. Around 1350 BCE, Prince Thutmose of the royal house mummified his beloved pet cat and buried it in an engraved stone coffin. While this luxurious burial is an early example of cat mummification, the tradition would continue until late Roman Egypt.

The sarcophagus of the cat of the Crown Prince Thutmose, the eldest son of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. (Photo: Larazoni via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Contrary to popular belief, the ancient Egyptians did not worship cats. Rather, they revered them as sacred to deities. Cats were respected for being fierce hunters and protectors of their homes and young. They could be sweet at times, warrior-like at others. While there is clear evidence that many Egyptians adored their family pets, these pets likely were useful, too, as mousers and snake-hunters. These household cats often wore collars as pets do today.

“Cuff Bracelets Decorated with Cats,” New Kingdom, circa 1479–1425 BCE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Bastet, the Feline Goddess

“Bastet,” Late/Ptolemaic Period, 664–30 BCE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Cats were sacred due to their association with the gods, particularly with the goddess Bastet. Goddess of motherhood, fertility, and the home, the divine being initially sported a lioness head. However, as cats were domesticated and became associated with the home, Bastet developed the head of a house cat. Egyptians could wear cat amulets to invoke her protection and blessings. They also created countless sculptures of cats as votive offerings to the goddess. Cat cemeteries devoted to the goddess grew into an industry, with cats specifically bred as offerings.

“Amulet, cat,” lapis lazuli, New Kingdom, circa 1550–1295 BCE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Cat Mummies

“Box for animal mummy surmounted by a cat, inscribed,” Late/Ptolemaic Period, 664–30 BCE (Photo: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The cat cemeteries, full of votive offerings to the goddess Bastet, turned up countless cat mummies during 19th-century excavations by archeological teams. From adults to kittens, these cats were mummified much like humans at the time. Many were wrapped carefully, with decorative head coverings. Others were encased in cat statues or decorated sarcophagi.

“Sacred animal mummy of a cat,” Roman Period, circa 400 BCE–100 CE (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Aside from these collections of feline mummies, cats were also buried with their humans. Cats had an important role in the Book of the Dead. Owners believed they would be reunited with their miniature protectors in the afterlife. Other owners chose to bury their beloved pets in purpose-made pet cemeteries, where archaeologists have found evidence that the cats were well cared for and often died of old age.

While cats remained revered in Egypt even after the Roman occupation, the Christianization of the empire largely ended the tradition of cat mummies and offerings to Bastet. Today, the domestic cat still remains heavily associated with the art and culture of ancient Egypt.

“Rock crystal amuletic figure of Bastet as a seated cat; the ears and forelegs are lost.” New Kingdom. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Related Articles:

3,400-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Painting Palette Still Contains Remnants of Pigments

Archeologists Accidentally Discover 250 Rock-Cut Tombs in Egypt

4,500-Year-Old Egyptian Wood Statue With Rock Crystal Eyes Boasts Incredible Craftsmanship