Photo: Stock Photos from Steve Heap/Shutterstock

Climate change is a common term used to refer to “a change in global or regional climate patterns.” It is often used in conjunction with the greenhouse effect and reports of rising sea levels. But there's another term in the eco-conscious sector of culture known as climate gentrification. So, what is climate gentrification? Gentrification is the changing of a poor urban area as affluent people and businesses begin to move in. It is viewed as a negative change since neighborhoods often lose their character and services or businesses may be reallocated to serve wealthier, new residents instead of the people who were using them before. The worst and most cited fear surrounding gentrification is that low-income residents, and disproportionately people of color, will be priced out and displaced from their homes. Climate gentrification is simply the same process motivated by the effects of our changing climate and the need for low-risk ground away from rising sea levels.

It is important to understand that climate gentrification is not the act of moving because of climate; it is the process of people being priced out as the prices of real estate and maintenance become too high for them to live there. Climate change is already having an effect on land and real estate. As we face more extreme and more frequent weather conditions, this effect will only become more drastic. Areas that are near water or other locations that are affected by weather will become more expensive to live in. People have to think harder about expenses like insurance and rising taxes to mitigate the costs of protecting and repairing property. Land that is safer will also rise in value. Examples of these predictions are already happening around the world. In this article, we cover the types and expectations of climate gentrification and break down some real examples to help you understand the challenges facing our communities.

Defining Climate Gentrification

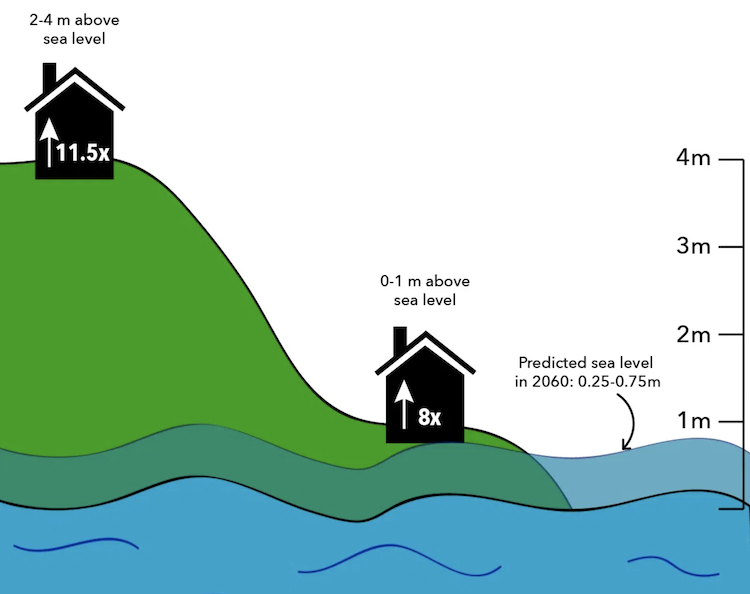

Climate Gentrification (Photo: Harvard University)

Jesse Keenan, Thomas Hill, and Anurag Gumber are researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Design who first coined the term climate gentrification. They believe that though climate has always had an influence on real estate, its effect will become dramatically more significant in the next decade. Keenan explains that “the higher elevation properties are essentially worth more now, and increasingly will be worth more in the future. Populations, including speculative real estate investment, will densify in these high elevation areas.” Though this is the general conclusion, Keenan has developed a more specific theory of three “pathways” in which climate will force gentrification and displace communities.

Three “Pathways” Toward Climate Gentrification

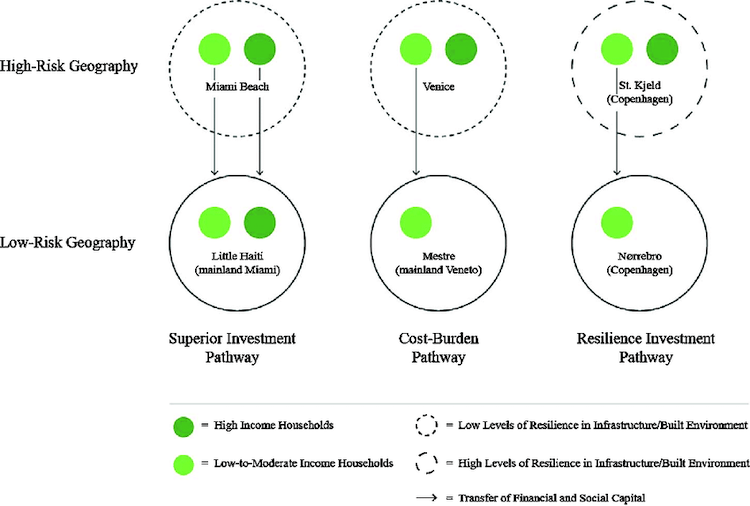

Three Pathways Towards Climate Gentrification (Photo: Harvard GSD Research from Jesse Keenan, Thomas Hill, and Anurag Gumber)

Superior Investment Pathway

Areas that will suffer less effects from weather conditions will gain value as people flee their high-risk communities for a safer and more secure environment. This may happen as wealthy communities on waterfronts seek a safer and more reliable property or as fires become more frequent in hot, dry areas. The demand for these properties will surge real estate prices up. This surge in price can gentrify the low-risk area.

Cost-Burden Pathway

On the other hand, the high-risk areas like those more prone to hurricanes, flooding, or wildfires become so expensive to maintain or insure that no one but the very wealthy can afford to live there. This is the opposite situation as Keenan’s first pathway, but has generally the same result. As the diverse and mixed-income areas rise in price, the low-income residents will be priced out and will begin moving away to low-risk areas.

Resilience Investment Pathway

The last pathway suggests that governments will invest in resilience methods and infrastructure. The land that is protected against the effects of climate change become far more valuable. This has a similar effect to the first pathway, meaning that existing populations who cannot afford the rising valuables will be displaced from that area. This is especially an issue since these investments will most likely be planned to serve the entire existing community, but the new infrastructure will change the very fabric of the neighborhood.

Climate Gentrification in Miami

Photo: Stock Photos from meunierd/Shutterstock

As climate gentrification has become a more common term and understood as a factor facing our cities, Little Haiti has become its most easily recognizable example. This is partly due to the Harvard GSD’s research study that covered Miami and highlighted Little Haiti as a future climate gentrification site, but the area has also been known as an increasingly developing area of Florida fighting to survive.

Projections for future flooding of Miami-Dade County suggest that sea levels will rise by six feet by the year 2100, causing the displacement of 800,000 people, or nearly a third of the population. This will cause a migration of people, many of whom owned or rented the most expensive waterfront properties and would bring up the prices of the higher land. Many believe that Little Haiti is the most likely to be gentrified when this happens.

Photo: Stock Photos from meunierd/Shutterstock

Already, Little Haiti is feeling the effects of rising real estate prices. Community centers, schools, and other necessary services for Little Haiti have been forced to move buildings when they could no longer afford the land. Magic City, a $1 billion high-end development, is planned for the outskirts of Little Haiti and its new apartments and buildings will bring a new crowd to the community. People who currently live in Little Haiti fear that once they are priced out, they will have to move far from their community to be able to afford a place to live.

Little Haiti is just one example of the threat of climate gentrification. Unfortunately, we can expect to see more displacement and inequity as weather and flooding worsens. Understanding these events may be the first step to understanding why they happen and implementing policy changes to address them.

Related Articles:

The IEA Announces Solar Power Is Now the Cheapest Form of Energy

Canada Will Ban Plastic Bags, Straws, Cutlery, and Other Single-Use Plastics Starting in 2021