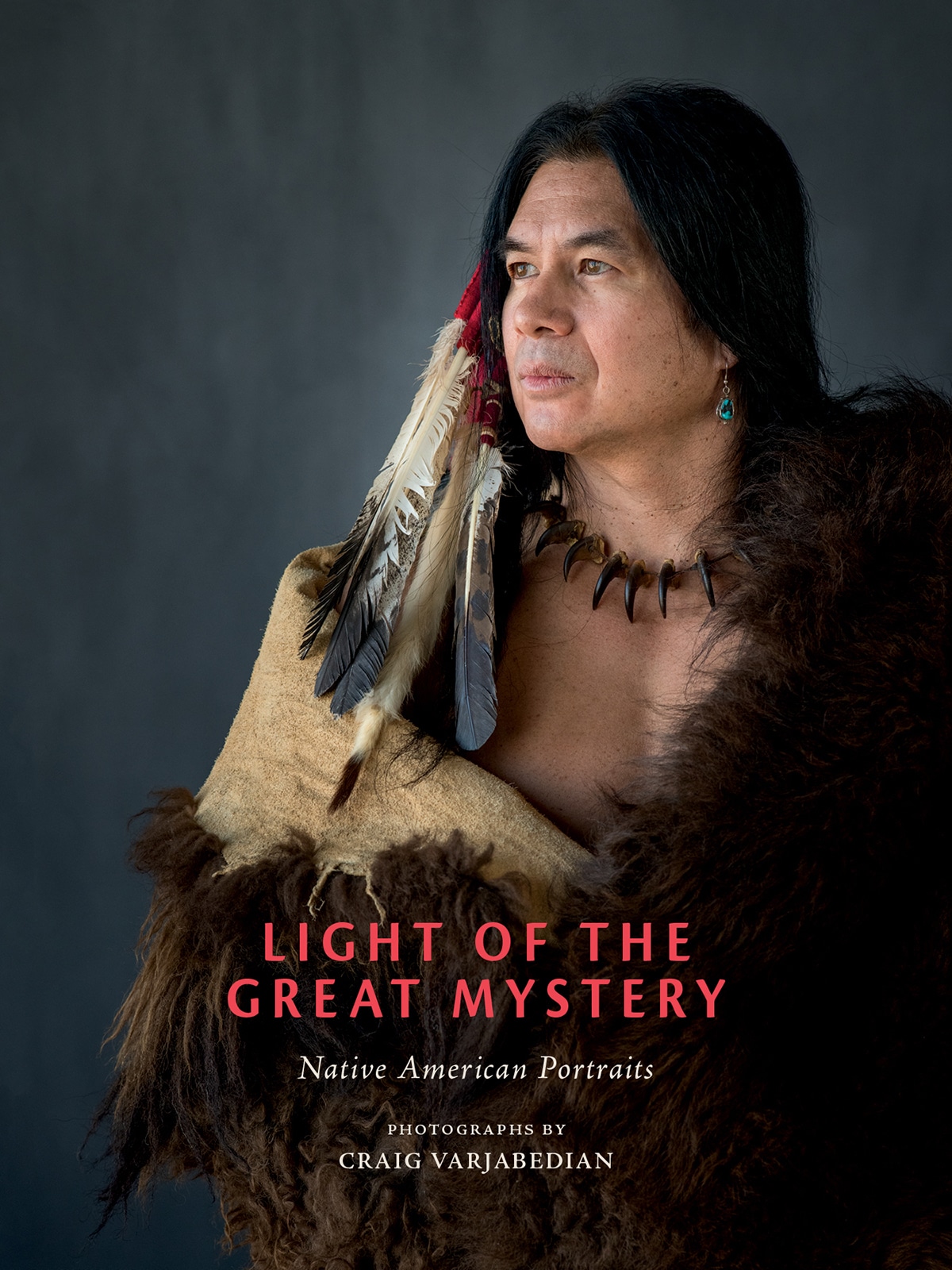

Larry

Photographer Craig Varjabedian is known for his stunning portrait series celebrating the lives and cultures of Native Americans. The Native Light Photo Collaboration project sees Varjabedian working with Indigenous people around New Mexico to create photographs that highlight their spirit. By working together, photographer and model have equal control and, therefore, the images avoid the exploitation that can sometimes occur in this genre of photography.

Varjabedian works closely with each Native American who sits for a portrait. Together, they find what works in order to tell the story of the individual's cultural identity. By cultivating trust, Varjabedian is able to pull out beautifully expressive imagery that speaks to the deep ties each person has to their roots. His work doesn't focus on the sitter as “exotic,” as often happens, but portrays them as an equal who is actively involved in how they are portrayed.

“I am compelled to enable these efforts by my portrait participants on their terms, and as a part of their process of either celebration or bridging the cultural disconnect visited upon them, because I am also a member of a people that were considered ‘the other' and targeted for extirpation—my grandfather fled the Armenian Genocide of the early 20th century,” he writes. “That devasting historical episode had a profound impact on my family, so the experience of cultural disconnection through trauma is very real and personal to me, not merely a concept.”

Varjabedian continues his exploration of the American West and hopes to branch out beyond New Mexico as soon as it's possible. To help fund the project, he sells everything from notecards to a high-quality printed portfolio via his website.

We had the chance to chat with Varjabedian about the Native Light Photo Collaboration and what makes him so passionate about his work. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

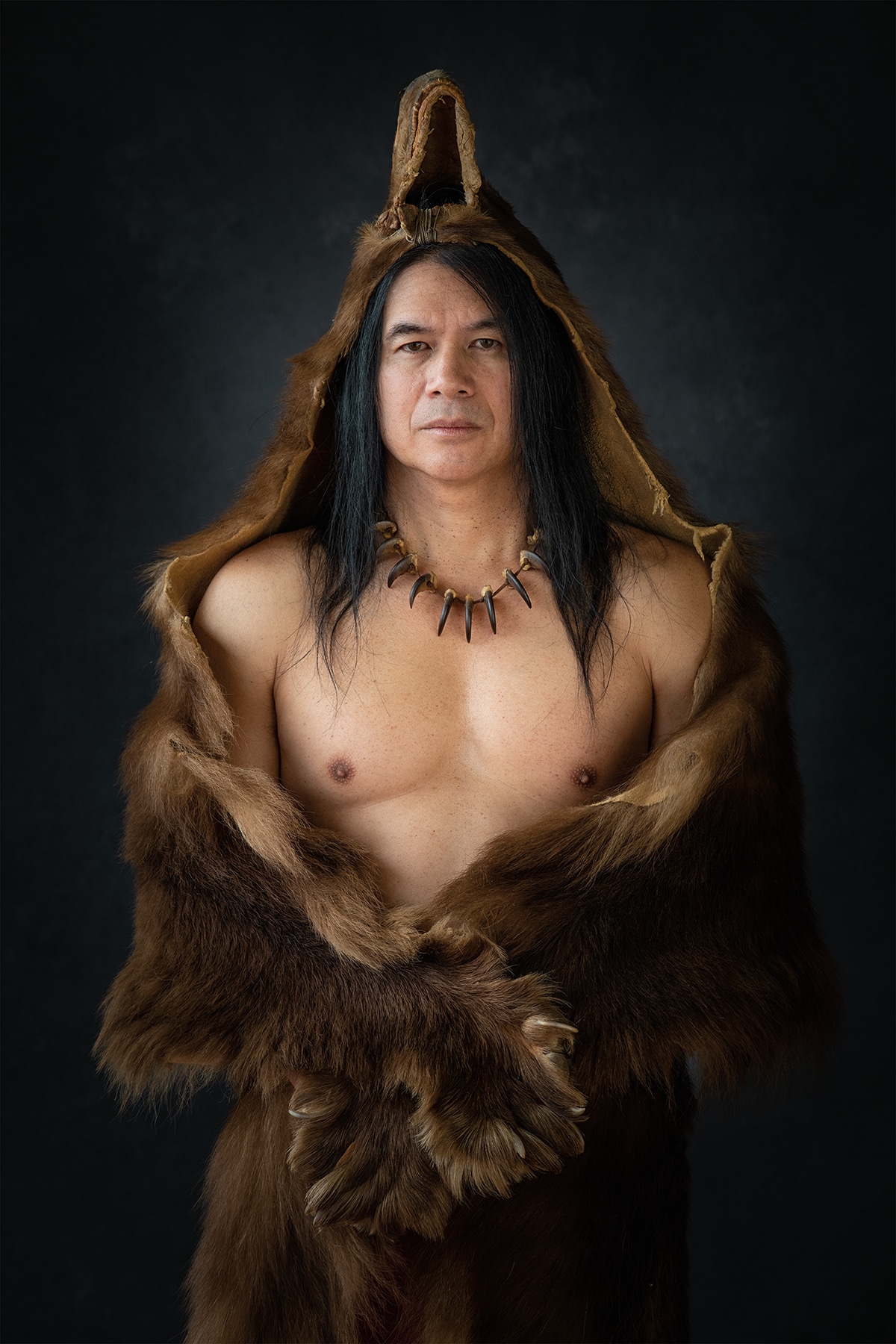

Redhawk

I know you were inspired by Edward Curtis‘ work. Can you share a bit about how you first encountered his photos and what moved you about them?

Edward Curtis was an amazing photographer. I first encountered his images while attending a photography history class at the University of Michigan years ago. I remember being deeply moved by what I saw projected on the screen that day. After class, I raced to the art library to view more of Curtis’ work and was elated to learn more about, and eventually study, the vast number of photographs he made. For me, Curtis’ images reveal something awesome (in the truest sense)—something that is majestic and universally human and beyond words. There is a flow of energy within the great photographer’s images that transports the people portrayed into the present and, in turn, makes them timeless.

Rodrigo Bear

What's been the biggest challenge and biggest success for the Native Light Photo Collaboration?

The biggest challenge facing our Native Light Photo Collaboration right now is waiting for the COVID-19 pandemic to abate so that it will be safe to continue making pictures. But in order to speak about the challenges of this project, it is important to preface these statements with the idea that Native Americans do not all think and speak with the same mind. What may be an issue for one person might not be for another.

With that said, perhaps the biggest obstacle we have to overcome in making these pictures is the relationship many have with photographers and photography. To a group of people who have been consistently lied to and promises (treaties) broken, it is no wonder that some are wary and even distrustful of having their photograph made. Some believe that making a photographic portrait is simply wrong for a variety of reasons, such as believing the camera will steal their soul. Others have seen or experienced first-hand, contempt from photographers who make crude, disrespectful, and even sexualized images that attempt to trivialize them. And there is the backlash over the surreptitious photographing of private sacred rites which has happened numerous times throughout the history of photographing America . . . the list goes on and on.

Diné

(continued) Given a long history of cultural misappropriation, Indigenous people are rightly suspicious that non-Indigenous people may abuse or misuse their traditional ways. My friend Marlene Bad Warrior who is Diné writes, “We were never meant to be here. Through the smallpox infected blankets, stripping of language with lye soap, the long walks, massacres, and kidnapping of children, here we are now. In this now, there is a reclamation of soul, culture, medicine, and prayer. Our resurgence is molded by our past and infused with the presence. We are consistently evolving past our expected extinction, expanding our knowledge of our truth and telling our stories.”

We hope our biggest success for the project will be through our sincere commitment to create a body of authentic and respectful images that honor not only Native American life but also the men and women who grant us the privilege of photographing them. As the word gets out, we are receiving a lot of positive support from people who might not otherwise choose to participate.

Tanysha

How do you go about finding the people who sit for your portraits?

Generally, I make connections with the people I photograph through word of mouth from a network of people across the American Southwest, built over many years of working here. One person tells another about my work and so forth.

In order to make what I believe is a successful portrait, it is necessary to connect in some way with the person I am photographing.

Trust must be established and this takes time. I genuinely and deeply care about the people I photograph. We talk and share stories and eventually find common ground. Through getting to know that person, we connect and trust is hopefully established. I endeavor to create a portrait that reveals something deeper and more personal about the person being photographed.

Yanabah Moonsky

(continued) I also reach out to people I discover through social media and follow them for a while, eventually sensing from the way they present themselves that they might be good subjects. This also works in reverse, in that people will see my images on social media and reach out to me to be photographed. It’s quite a wonderful thing.

To date, I have made portraits of Native Americans living in or visiting New Mexico, and have traveled the state to facilitate the portrait sessions. Once the current pandemic has abated, I want to go on the road again to meet new people and connect with those who have reached out and want to become a part of our project but are unable to travel to New Mexico.

Marlene and Jayme

What kind of collaboration goes into what your Native American subjects decide to wear and how they pose?

The process of creating an authentic photograph is a collaborative one. Participants come to be photographed with a variety of objects, clothing, and regalia—each item bearing with it a history and deep personal significance. Oftentimes, it is what the participants are wearing, and how they want to present themselves, that suggests what additional objects can be added to a possible photograph. I ask people to bring items of deep meaning that are appropriate to what they are wearing and also important and significant to them. The process of collaborating makes possible a resulting image that is true to the person being photographed.

Marquel, a Tewa woman I photographed whose traditional name is Thamu Tsan (meaning Sunrise), wrote about this work, “The greatest impact of this project lies in the collaborative approach to each photo—partnering subject and the artist—that shifts that power paradigm of the traditional visual representation of Native American people in American art, updating outmoded ideas about Native cultural identity and representation.”

Deer Dancer

(continued) Most participants are presented in precious regalia and ceremonial attire while others are pictured in traditional attire, adorned with ornate turquoise jewelry. Some wear a delicate display of feathers in their hair while others exhibit a striking bustle of feathers and fringe that extend outward into space. Several accessorize with beaded shell necklaces and leather moccasins whereas a handful opt to drape themselves in the comfort of a wool blanket and animal pelts. When you take a closer look at the objects, you will find layers of meaning and symbolism—ornamental shells and animal motifs, vibrant patterns, geometric shapes, and intricate beadwork.

It may come as no surprise that many items of clothing, accessories, and ceremonial objects are deeply rooted in meaning and family heritage. These often hand-made items are emblems of self-preservation, history, and tradition. They are signifiers of tribal representation, ancestry, and spirit. They are symbols of time, identity, and personal narrative. They are embodiments of individuality and self-presentation. For many, the regalia is passed down from generation to generation, making its way through the hands of ancestors, grandparents, and family members.

Kai

How do those who sit for you inspire you creatively?

The inspiration for these images was first discovered many years ago out on a vast plain just south of Santa Fe. My friend Anthony, an Omaha Native American, walked out into the tall grass in his most beautiful regalia. The sun was low on the horizon and the light was turning everything a beautiful shade of pale luminous orange. Just when I was about to release the shutter, my friend Sadie’s hybrid wolf wandered into the scene and joined the moment. As Chief Dan George aptly observes in the film Little Big Man, “Sometimes the magic works, sometimes it doesn’t.” This time the magic worked.

I have heard some Native Americans speak about something they call the Great Mystery. One of my favorite writers, Chief Luther Standing Bear, explains, “From Wakan Tanka there came a great unifying life force that flowed in and through all things—the flowers of the plains, blowing winds, rocks, trees, birds, animals—and was the same force that had been breathed into the first man. Thus all things were kindred and brought together by the same Great Mystery.” I hope these pictures offer a gift from that Great Mystery that Standing Bear speaks about. I believe the light that illuminates the people in front of my lens comes from that powerful place.

I photographed Thamu Tsan (Marquel) and her daughter Kai days after their pueblo’s corn dance. What I witnessed that cool autumn day on the plaza at Nambé Pueblo was as magical and transformative as communion in a Catholic church. I learned from Thamu Tsan that while the dancers and the drummers who participate in the dance work to be fully mindful and aware, everyone who attends the dance is also asked to be present in the moment; to be aware, as Standing Bear suggested, that all things are kindred and brought together by the Great Mystery. How we are being asked to attend in these moments remains a mystery to me as there is no formal request—yet it happens. One has to be open to the possibility. One has to be open to the moment.

Elk Deer

How do you hope these images shape the way that people perceive Native American culture?

The goal of our Native Light Photo Collaboration is to create awareness of the beauty and dignity of Native American culture at a time when the U.S. seems culturally divided. Additionally, it is our hope that the project will function as a teaching tool, a visual narrative that encourages learning and sparks a deeper conversation about contemporary Native America.

Native Light is an informative collection of portraits, displaying a rich record of cultural identity, personal narratives, and individuality. This visual document provides insight into the past, but also provides knowledge and education for the future. The photographs are chronicles of tribal representation, tradition, and resilience. They present valuable knowledge and awareness of Native American cultural identities for generations to come.

I am continuing to chronicle and photograph Native Americans across the American West and hope someday to enlarge the geographic scope of my work. Upon the project’s completion, a comprehensive book, as well as a traveling museum exhibition, is intended.

Yellow Flower

Any other thoughts?

I ask the viewer to fully attend while looking at this work, to be completely present as one might at a Feast Day dance. Thamu Tsan told me that when Native people dance they “walk in beauty”—everyone works together to create that beauty. The artist can only create the work and beat the drum to call the viewer to it. The viewer has to attend for the beauty to be shared. You are invited to attend.

Varjabedian's Light of the Great Mystery helps support the Native Light project and is available via his online shop.