Photo: Stock Photos from PISAPHOTGRAPHY/Shutterstock

If you have taken a train into New York City, you have probably ended up in the lofty halls of Grand Central Terminal. Alongside Penn Station, it is a major transportation hub of America's largest city.

With 44 platforms and 67 tracks (and counting), the train station serves the New York City Subway and the Metro-North routes to Connecticut and the Hudson Valley. The giant, constantly updating train schedules and the starry ceiling of the main concourse suggest a world frozen in Beaux-Arts style. The construction of the terminal ushered in the architectural innovations of the 20th century which remade Manhattan into its modern image.

Read on to learn more about the history of Grand Central Terminal, New York's legendary train station.

The Early Railroads of New York

Grand Central Station, in New York City, circa 1902. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The present-day Grand Central Terminal is built upon the site of the similarly named Grand Central Depot. This enormous French Second Empire-style train depot was constructed out of a need for train platforms on 42nd Street. In the mid-19th century, trains belching soot were forbidden below 42nd street as lower Manhattan was the city's vibrant residential center.

Trains were nonetheless important to supplying the city and serving its ever-growing population. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the transportation baron of the Gilded Age, appointed architect John Snook to design a large station for his two major railways. The depot opened for use in 1871 and served three railroads: the Hudson, New Haven, and Harlem Railroad companies. These lines helped unite the tri-state area and were symbolized in the depot's three-towered design.

Planning and Building Grand Central Terminal

Excavations for Grand Central Terminal. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

By 1900, the Grand Central Depot was in need of an update. New York City had continued to expand and grow, requiring a better solution to the city's evolving transportation needs. In 1903, a competition was held for new station designs. The winning architectural firm Reed & Stem based their designs on the fluid movement of people via ramps. The magnificent arched stone exterior of the building was the work of another firm, Warren & Wetmore. Together, the firms shared the monumental building project. Excavation and building were done in strategic phases so as not to block all traffic to the critical station. By 1913, the new building was open and operational.

Inside the magnificent new building was—and still is—a space both decorative and functional. The ramped passageways leading between concourses and platforms feature vaulted ceilings. One vault, in particular, allows for careful whispers to be heard across the gallery. The marble walls and floors are accented by gilding and carved details of acorns and oak leaves.

A mural by artist Edward Trumbull in the Graybar Passage is a must-see. Painted in 1927, it shows an electric train in homage to modern transportation technology. The outside of the building displays art as well. An enormous sculptural group by Jules-Félix Coutan features a large clock and winged Mercury among other allegorical images. Known as the Glory of Commerce, it is a monument to both modern technology and, seemingly, the guiding force of the Vanderbilts.

The Famous Main Concourse

Photo: Stock Photos from SEAN PAVONE/Shutterstock

The main concourse is the crown jewel of Grand Central Terminal with its large hall and lofty barrel-vault ceiling. Today, travelers will find an information booth and ornate four-faced opal glass clock. Famously seen in many movies and TV shows (such as the opening of Gossip Girl), the concourse is a meeting place for travelers and loved ones.

In 1944, a painted wooden ceiling in an elegant blue replaced the original ceiling mural. The new version displayed the same constellation design which has become a famous New York City Landmark. At one end, a series of balconies and archways provide access to other halls, passages, and platforms.

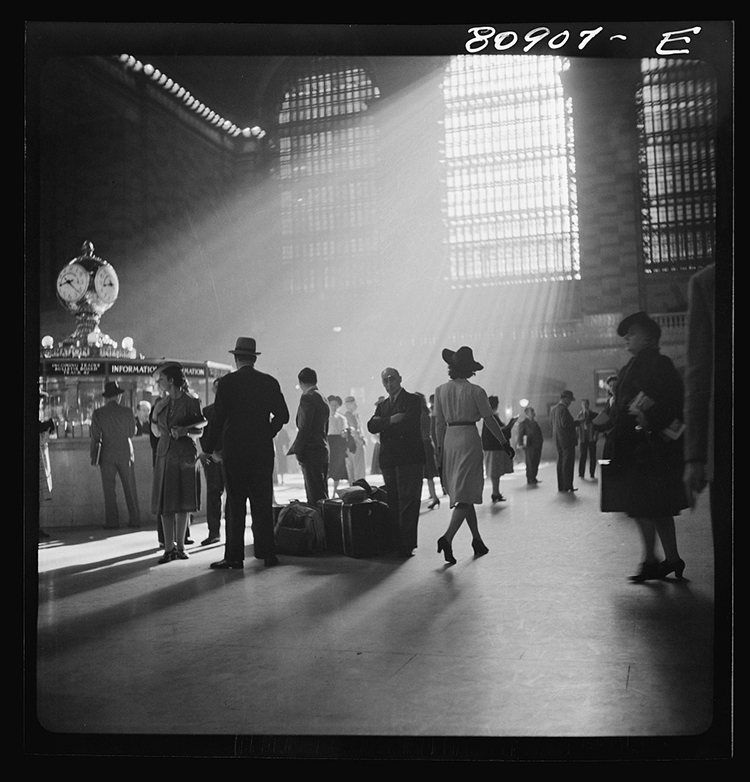

The main concourse, 1941. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

During World War II, the main concourse became a center for the promotion of the war effort with large banners advertising war bonds. This mid-century period was the peak of rail traffic through Grand Central. By the 1950s, commercial air travel began to chip away at the long-distance railways. However, the terminal remained an important city institution. Advertisers used the space and traffic to their advantage—the enormous luminous Kodak Colorama display hung over the concourse for decades until 1989.

Passages, Tunnels, Dining, and more

Photo: Stock Photos from TTSTUDIO/Shutterstock

Grand Central Terminal is much more than just a train station. The building once hosted art galleries and even an art school. In 1987, performance artist Philippe Petit walked across a high-wire strung through the building. The terminal has hosted radio and television shows, boxing matches, and countless wedding photoshoots. There is also a library, a tennis court, and a modern Apple store.

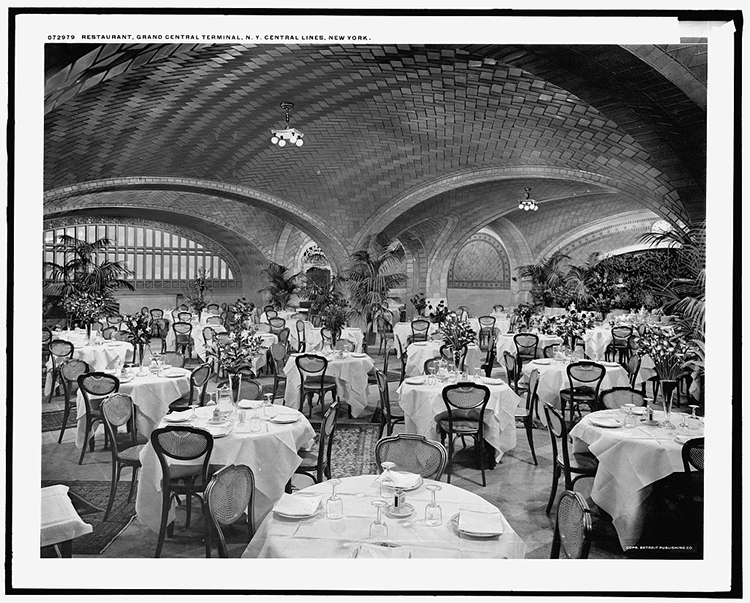

Restaurant at Grand Central Terminal, circa 1910 to 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

As diverse in its offerings as a small city, the terminal is known for the food options which have been available to visitors since the early 20th century. Modern diners find casual dining options, but there are also several storied restaurants, including The Grand Central Oyster Bar & Restaurant which opened in 1913. Upstairs, the CBS Studios became tennis courts. The Campbell bar is also a remnant of the opulence of one of the space's original tenants—the millionaire John W. Campbell.

Whether you are dining at the Oyster Bar or merely running for your train, to visit Grand Central Terminal is to experience a sliver of New York history.

Related Articles:

Empire State Building Offsets Its Energy Use in an Ambitious Wind Power Deal

Paris Was Rebuilt: How Baron Haussmann Created the Metropolis We Know Today

10 Facts About Antoni Gaudí the Creative Madman Behind La Sagrada Familia [Infographic]

15 Beautiful Cathedrals Around the World That Are Full of History and Spirituality