Herculaneum papyrus CT scan by Dr. Brent Seales in 2009. (Photo: University of Kentucky/Brent Seales)

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, the volcanic ash that buried Pompeii both preserved and destroyed precious traces of ancient culture. For all the mosaics, sculptures, and wall paintings that survived, there are still many mysteries to be solved. This includes deciphering a wealth of text hidden in scrolls that were charred beyond repair. But now, one scholar is using cutting-edge technology to reveal their contents.

Herculaneum, a wealthy town close to Pompeii that was also buried by the volcano, was first excavated in the early 18th century under King Charles III of Spain. It was then that over 1,800 scrolls were discovered in a luxurious retreat named the Villa of the Papyri. With ancient text being the best way for historians to understand life in the ancient world, the discovery should have been a joyous occasion. But the scrolls were charred and blackened—carbonized by the eruption.

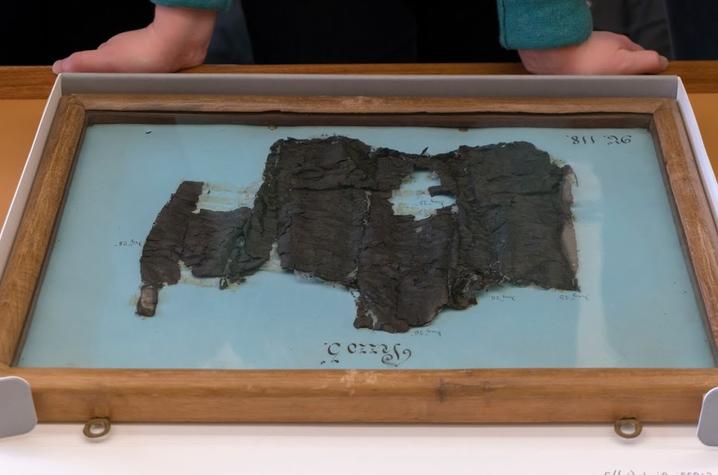

Early attempts to read the scrolls failed miserably. Physical attempts to unroll them resulted in crumbling flakes that were largely unreadable. Many were also destroyed as workmen mistook them for pieces of coal and tossed them away or burned them for heat. What little text has been read suggests that they are Greek philosophical texts. Since their discovery, archaeologists have been attempting to find ways to unravel the mysteries locked inside without damaging the fragile remains.

Carbonized fragments of the Herculaneum papyrus known as PHerc.118. (Photo: University of Kentucky)

Brent Seales, a professor of computer science at the University of Kentucky, first became interested in using new technology on the Herculaneum papyri in 1995. After seeing how special software and 3D visualizations helped preserve the British Libary's copy of Beowulf, he wondered if the same process could be applied to the scrolls. The procedure, akin to a CT scan that studies the body, would scan the scroll without physically touching it and digitally flatten it.

Unfortunately, the theory was easier than the reality. It wasn't until 2009 that Seales was able to convince one of the major holders of the scrolls, the Institut de France, to let him attempt a scan. While the scan allowed him to see inside the scrolls, there was something he didn't account for. Seales had been banking on the presence of metals found in ancient ink to help him separate the text from the papyrus. But shockingly, none could be found. It was also impossible to separate the carbon from the paper and the carbon from the ink. This left Seales with a view that was undecipherable.

Herculaneum (Photo: javarman via Shutterstock)

From there, he set about creating a program that would be sophisticated enough to process the terabytes of data from the scan, something which took several years and time spent at the Google Cultural Institute. Later, he joined forces with the Dead Sea Scrolls Project. He was able to use the new technology to virtually unravel a scroll from En-Gedi, Israel and flatten it. As that scroll was made from animal skin, there was more contrast with the ink and scholars were then able to read the scroll, which contained early text from the Bible. In fact, aside from the Dead Sea Scrolls themselves, they are the earliest known texts from the Bible.

Thanks to this exciting breakthrough, Seales—and researchers around the world—are more optimistic than ever that his technique can allow them to read more ancient scrolls. Though progress is largely depending on funding, advances in X-ray technology that isolates even trace amounts of ink means that another breakthrough might be right around the corner.

h/t: [Open Culture, Mental Floss]

Related Articles:

Scientists Piece Together One of the Last Unsolved Dead Sea Scrolls

This 4,000-Year-Old Tablet Could Be the World’s Oldest Customer Service Complaint

11,500-Year-Old Infant’s DNA Reveals New Surprises About How North America Was Populated

Laser Mapping Unearths 60,000 Ancient Maya Structures in Guatemalan Jungle