Wellesley College students, 1903, by E. Chickering & Co. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Panoramic photos are almost as old as photography itself. Photographers have been capturing horizontal landscapes and large groups of people using a variety of techniques over the last century and a half. As photographic processes and camera technology evolved, so did the panorama. What began as a cumbersome process for professionals eventually morphed into an easy-to-use mode on the ubiquitous smartphones held in everybody's pockets. Today, a panoramic photograph is just one of many options available for photographing our daily lives at the touch of a button.

Typically, a panorama indicates a wide field of view—an image wider than it is high, so to speak. One might hear reference to a panorama of a city skyline or a mountain range. While panoramic photographs are important to landscape photography, the format is also used for other purposes—such as class photos or 360-degree views.

A true panorama is generally an image that covers about 160 degrees of view or wider. In general practice, however, the term is often used for images taken with a fixed-lens camera and shows a view that is significantly wider than it is tall.

Read on to explore the history of the panorama and see how this medium has developed over the decades.

Western approach to the Acropolis, Athens, 1842. Daguerreotype by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Panoramas on Plates

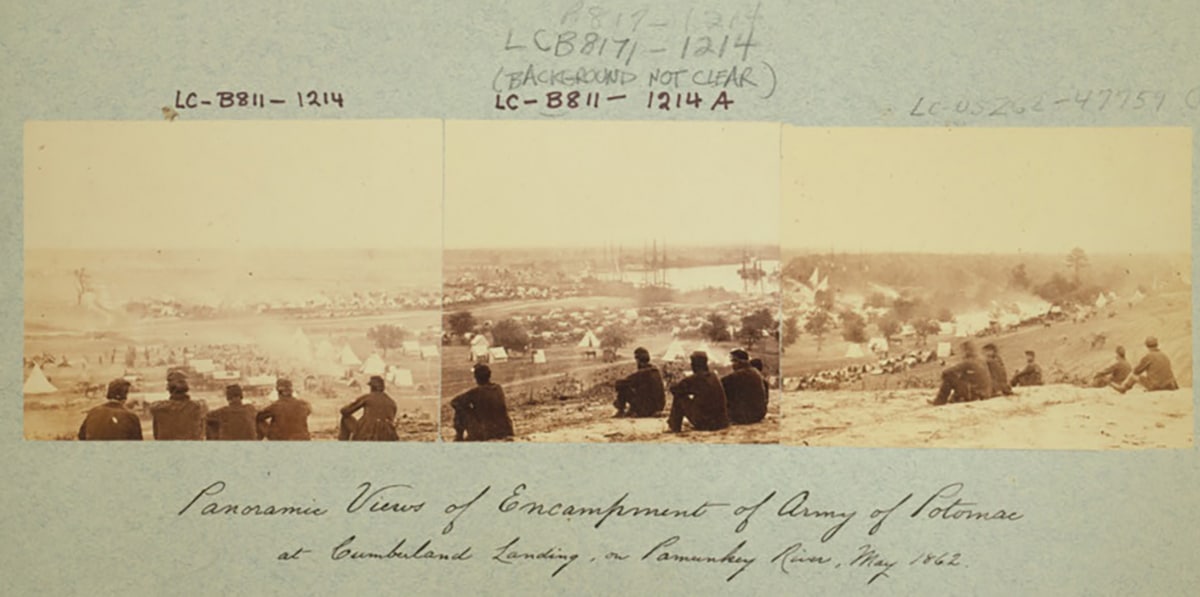

Panoramic views of the encampment of the Army of Potomac at Cumberland Landing, on Pamunky River, May 1862. Taken on three plates by Williams & Rogers. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The daguerreotype was the earliest widely-used photographic technique. A copper sheet was made light-sensitive with a silver and chemical coating. This plate was then exposed in a camera. Next, the plate was developed using mercury vapor and other chemicals which brought forth and preserved the photographic image. This laborious process produced a unique image—unlike later methods which would produce negatives from which multiple prints could be made.

As early as 1843, specific cameras began to be designed for panoramic photography. These designs were rotated—or panned—by a manual crank to cover a wide field of view. As the camera lens rotated, successive plates (or at times one long plate) were exposed.

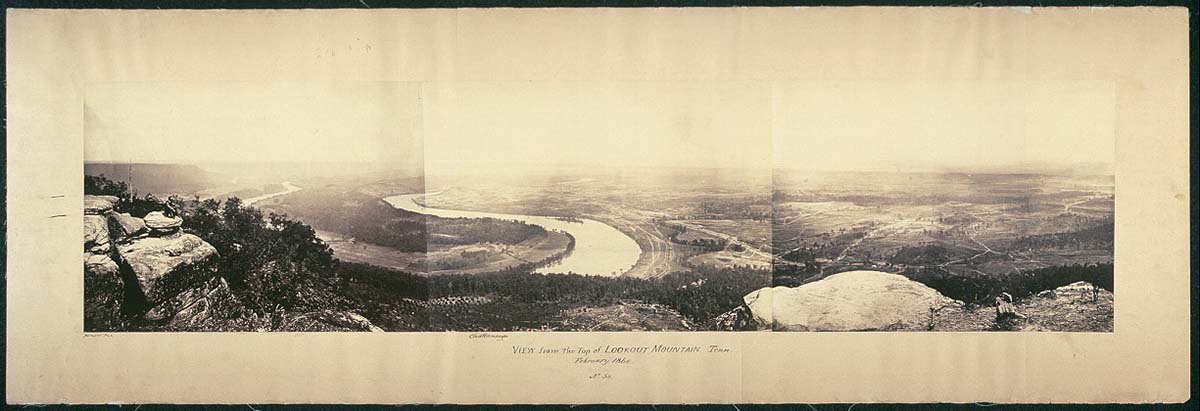

View from the top of Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, February 1864. Shot by George N. Barnard on three plates. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The resulting images could be pieced together to form one long series of connected image. The same approach to creating panoramas continued to be used as the wet plate collodion process replaced the daguerreotype in the 1850s. Wet-plate photography was easier and cheaper. The glass plates were exposed in-camera and then processed, after which the plates served as negatives from which prints could be made. Panoramic prints could now be easily reproduced. Like with daguerreotype plates, however, the photographer still faced several challenges. The plates had to be evenly aligned, and the movement of the camera also had to be smooth to avoid the “banding” of an image resulting from changes in speed. The distortion of lines and perspective was also largely unavoidable.

In the 19th century, photographers took on ambitious panoramas of everything from cityscapes to Civil War encampments. The panoramas of George Barnard—a photographer for the Union Army—were considered tactical tools for army engineers and military leaders planning their defenses. Today, these images are valuable historical records of local landscapes.

The Possibilities of Flexible Film

Bathing Girl Parade, Seal Beach, California. Shot by M.F. Weaver, circa 1917. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Flexible photographic film was first developed in the 1880s. Whether as rolls or sheets, this new material inspired a range of cameras which made panoramic photography available to amateur photographers. This development was part of a much larger commercialization and democratization of film photography that was largely led by the affordable cameras and clever marketing of the Eastman Kodak Company.

Panoramic cameras using flexible film typically fell into two categories. With the swing-lens cameras, a lens rotated as it exposed a “slit” of image over stationary film. In the 360-degree rotation cameras—also known as rotating panoramic cameras—the camera lens rotates while the film is pulled along by a synchronous motor.

Ready-Made, Consumer Panoramas

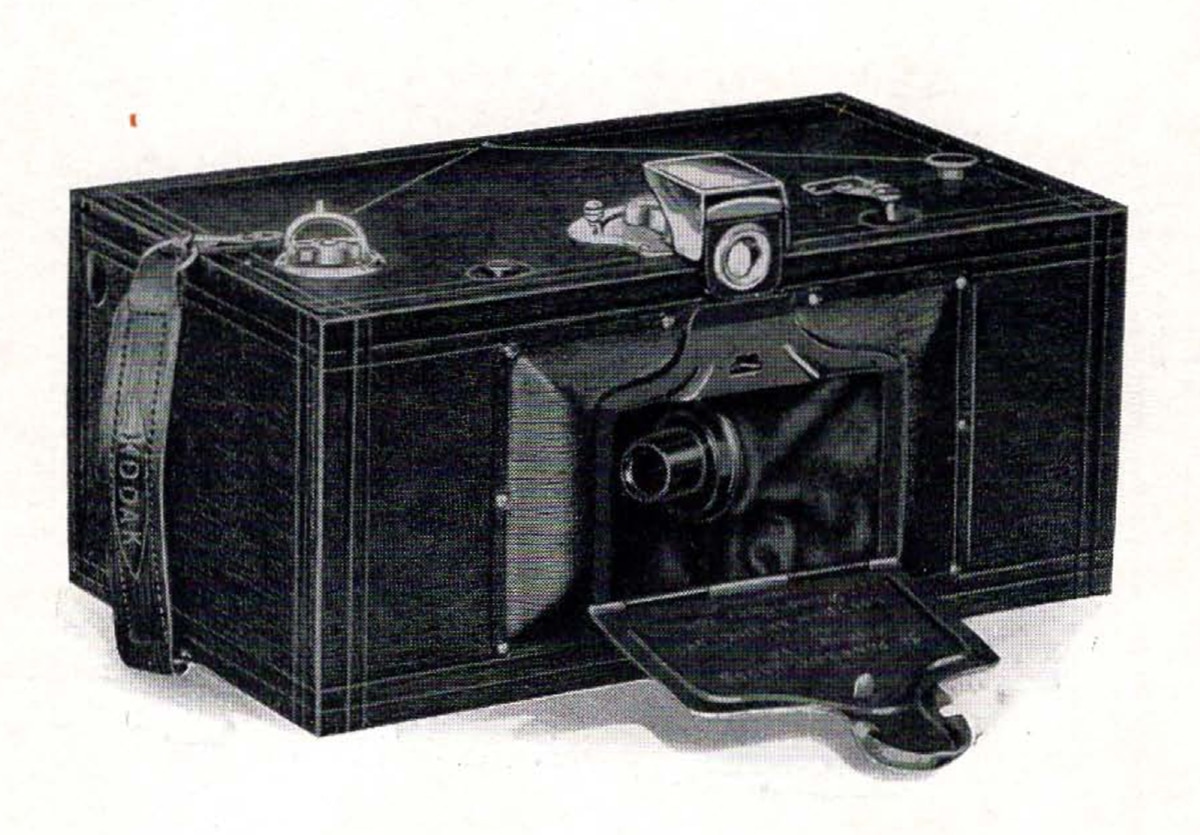

The Kodak No.3A Panoram, produced from 1926-28 but a similar design to the earlier models. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The first consumer panoramic camera was the Al-Vista, released in 1898. The swing-lens camera came to be produced in multiple sizes as film was sold in a variety of widths. Inside the camera, a spool held the film and advanced the frames over a curved plane. The lens would sweep across the film plane to expose the film. This motion could be set at different speeds to match the lighting conditions (i.e. the slower the speed, the darker the conditions).

Shortly after the release of the Al-Vista, Kodak released its own consumer swing-lens panoramic camera based on the designs of Frank A. Brownell, the man behind the Kodak Brownie. The No.4 Panoram and No.1 Panoram were both being sold by 1900. Though similar in design, the No. 4 offered a larger negative, a wider field of view, and cost more. Various models of the Panoram continued to be offered for sale through the late 1920s.

82 N. Latitude, panorama shot during the unsuccessful Ziegler polar expedition of 1903-1905. Taken on a Kodak No. 1 Panoram camera. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The relatively affordable swing-lens consumer panoramic cameras used rolls of film similar in size to today's 120mm rolls. However, professional photographers often used larger format rolls of film; these could be up to 16 inches wide and 20 feet long. It could be used to create contact print images by simply laying the large negative down on the photographic paper and exposing the surface. With this larger film, professionals tended to use a camera known as the Cirkut camera.

The Cirkut was a rotating panoramic camera where the film moved in concert with the lens. It was capable of a full 360-degree view. Introduced in 1904, the camera was bulky and required a tripod for use. The camera was produced in different variations until 1949 by a subsidiary division of Eastman Kodak. As described in an early catalog, the camera was versatile in a time when professional photographers still largely relied on plate glass negatives for use in their portraiture. “The Cirkut Panoramic Outfit is in itself a most complete affair being made up of a camera which can be used in the ordinary manner for plates when desired and a Panoramic Attachment which is easily and quickly attached to the camera, thus converting it into a Panoramic Outfit,” advertised the catalog.

Frederick W. Brehm worked for Kodak and helped develop the Cirkut camera. In his career as a professional photographer, he used the camera frequently. In 1906, Brehm made a 360-degree panorama of the Washington, D.C., cityscape. The panorama produced an impressive negative 20 feet long. However, most of Brehm's projects—like other contemporary panoramic photographers—revolved around the daily life of his city and its inhabitants. He photographed everything from soldiers to family reunions to baseball stadiums. In the work of Brehm and others such as Miles Weaver, the photographer arranged their subjects in a curved formation so that the arrangement would appear as a straight line on film. (Fun fact: While the camera was turning, some people ran around behind the camera to jump in the image a second time.)

A Gorizont Russian camera, 1967. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Over the 20th century, photography became increasingly accessible. Eventually, 35mm film came to dominate the consumer market. Plastic-bodied cameras operated on much the same principle as the early consumer swing-lens systems. These included examples such as the Russian Horizon camera, which was first released in 1967. Today, you can still experiment with compact 35mm panoramic cameras—including the Horizon. Other panoramic film cameras available today usually utilize a fixed lens approach, such as the beautifully designed panoramic pinhole cameras crafted by Ondu.

Digital Developments

An atrium photographed in 2003. Images from a Nikon Coolpix 5000, with a Kaidan pano head, and Manfrotto tripod. The image was stitched together using PTgui. (Photo: Rich Niewiroski Jr. via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5)

While film is far from dead, digital cameras dominate today. Much like the 19th-century panoramas created from multiple daguerrotypes or wet plate negatives, early digital panoramas were taken by snapping images as the camera rotated around an axis. By allowing the images to overlap some, computer software can then be used to “stitch” the digital images together. Another method uses catadioptric cameras—a system of mirrors and lenses—to capture an incredibly wide field of view from a single point. This image can then be flattened into a panorama. A benefit to this system is the ability to capture the entire panorama at one moment.

Today's Panoramic Photo

Skiing in Switzerland in March 2019, shot in panoramic mode on an iPhone 6. (Photo: MADELEINE MUZDAKIS/My Modern Met)

Today, most people are walking around with a digital approximation of the Cirkut camera in their pocket. The panoramic mode on a smartphone functions in much the same way as the antique cameras once did. The person holding the phone must rotate around an axis until the desired field of view is achieved. The camera digitally captures the image as it rotates—much like with a swing-lens camera. It is important to keep one's hands steady and speed even; move too fast and one will see banding of the image—a problem which panoramic photographers have faced for almost two centuries.

The medium with which photographers shoot panoramic images may have come a long way, but the images themselves are still impressive in their size and field of view. Next time you take your phone out to capture a stunning vista or photograph a party of family and friends, think of using your panorama mode. Maybe friends can run behind you, appearing multiple times in one image. Perhaps you can capture a full 360-degree view in your favorite spot.

Panoramic mode is full of possibilities. It's time to experiment!

The Adirondack Mountains shot on “pano” mode in the fall of 2020, iPhone 11 Pro. (Photo: MADELEINE MUZDAKIS/My Modern Met)