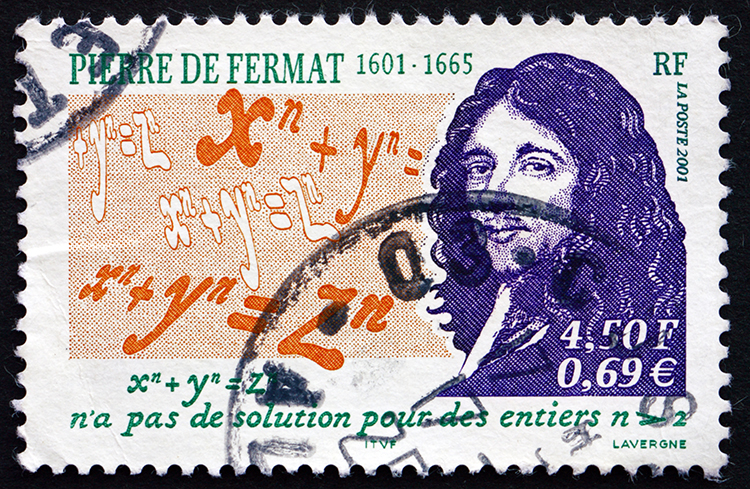

Pierre de Fermat, painted posthumously in the 19th century by Robert Lefèvre (1755-1830). (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

The great scientific minds of the Renaissance and Enlightenment often made contributions across myriad fields. Pierre de Fermat was no exception. During his lifetime in the 17th century, he made his mark upon optics, probability, analytic geometry, and even laid the some of the foundations for calculus (which Isaac Newton would later build on). His work has been appreciated and studied for centuries since his death in 1665.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of Fermat's legacy is the conjecture he left behind, known as Fermat's Last Theorem. This simple statement of mathematics seemed so true—and Fermat himself claimed to have a proof. However, that proof has never been found. For 358 years, generations of mathematicians struggled to prove what Fermat so confidently stated. A statement so simple in appearance became math's Holy Grail. The story of Fermat's Theorem—and that of the mathematician who would eventually solve the riddle in 1994—is a fascinating tale.

Who was Fermat?

Pierre de Fermat was born in late 1607 in Beaumont-de-Lomagne, France. The child of a wealthy family, he attend school as a young man to study the law. He then purchased (as was the custom) a position as a lawyer at the Parlement de Toulouse, a court. It was after his law training that Fermat began to seriously research mathematics. Although he remained an active lawyer, Fermat was one of the most prominent mathematicians of his time.

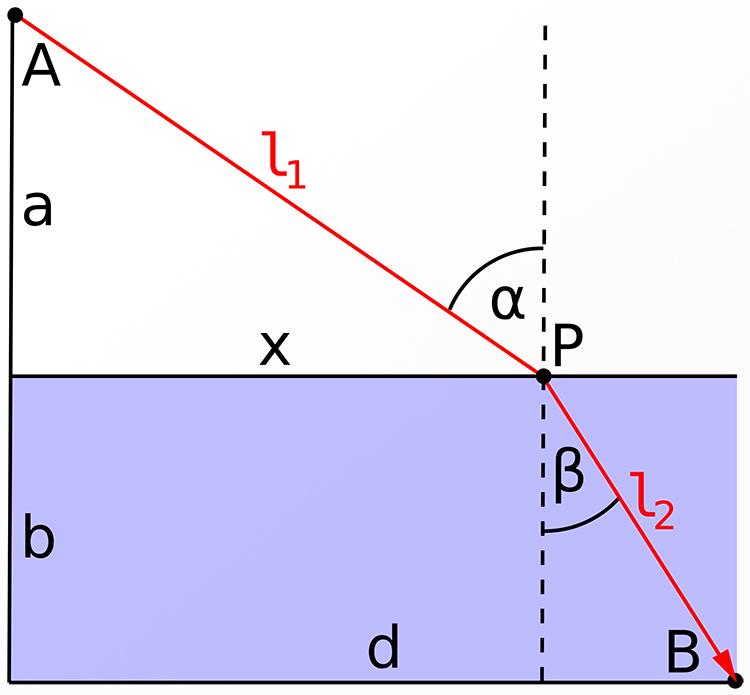

Fermat's Principle, linking ray and wave optics. This shows the refraction of light at a flat surface, such as the meeting of air and water. (Photo: Klaus-Dieter Keller via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Among his accomplishments was the work Methodus ad disquirendam maximam et minimam et de tangentibus linearum curvarum—a work which would prove foundational in analytic geometry. Fermat worked with the curves resulting from equations. He discovered how to calculate maxima, minima, and tangents. Doing just this would later become the point of differential calculus. Although Fermat's method was rather different, Isaac Newton himself credited it as an inspiration.

Like many great minds of the day, Fermat was part of the Republic of Letters. This was a network of thinkers and letter writers across Europe and the Americas, including some of the most recognizable names of the period such as Voltaire. Fermat's frequent correspondence with Blaise Pascal proved especially pivotal. Together, the two are credited with the emergence of probability theory. Fermat, for his part, initially used this knowledge to calculate the odds of a gambler—a problem which has since become famous.

What is Number Theory?

Photo: Stock Photos from AGSANDREW/Shutterstock

Fermat is perhaps best remembered for his contributions to the study of number theory. But to understand why Fermat's work is so critical, first we must ask what is number theory? The short answer is the study of numbers, their properties, and how they relate to one another. Specifically, number theory focuses on positive integers (whole numbers): 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on to infinity. Prime numbers are also of special interest and importance to number theory. In practice, number theory can seem as simple as the concept that the sum or difference of two integers is always another integer. It can also be as complex as modern public key cryptosystems—we owe our security on the internet largely to the development of number theory.

Although there are many applications and fields of research within number theory, you have actually done some number theory calculations yourself in everyday life. Say it is 11 o'clock in the morning, and you are headed out on a drive that will take you five hours, 11+5 would equal 16…which unless you are using military time is not valid on most clocks. In your head, you probably know that you will arrive at 4 p.m. How did you figure that out? You know that there are 12 hours on the clock. One hour from your start time, the clock will show 12. Then, the clock will start it's cycle from one to 12 all over again. So in one hour, it is 12, and we are left with four hours remaining to drive as the clock begins its next rotation.

That is a number theory calculation, although you may never have known this. In formal math parlance, this problem can be expressed as 11+5 (mod 12). The mod 12 stands for modulus 12. This means that, unlike normal addition, you are performing your modular arithmetic operation. There are only 12 possible numbers in a set, from one to 12. The answer to any addition or subtraction problem will fall within this group when taken mod 12.

To do so, simply divide the sum by the modulus, and the remainder will be the answer. For example, 54+61 is 115. But 54+61 (mod 12) is 7. This is because 12 goes into 115 nine times. The remainder from this long division is 7. By this principle, 19 (mod 12) is the same as 115 (mod 12).

What were some of Fermat's other theorems?

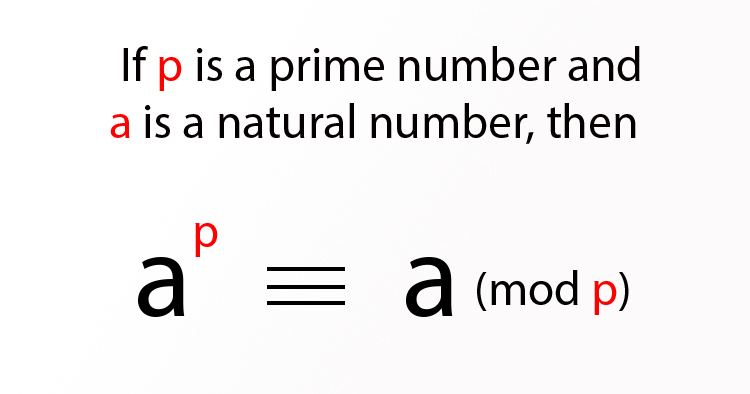

Photo: Stock Photos from BORIS15/Shutterstock

Fermat's Last Theorem is not the only discovery he is well known for. Within the realm of optics, Fermat refined the law of refraction with Fermat's principle. Fermat realized that light follows the path of least time, and his work established the law of reflection when light passes through to another medium.

A famous number theory contribution of Fermat's is known as Fermat's Little Theory. The theory states that a natural number a (natural meaning 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.) and a prime number p will always have a special relation—no matter what numbers you choose. If you multiply a by itself p number of times, the resulting number will reduce right back down to a when modulated by p. In short, the resulting number will be some multiple of p plus the value of a. This theorem (theorem meaning it's been proved true) is given below, in the statement most accessible.

P.S. The “triple” equal sign is actually a congruence sign, used like an equal sign in modular arithmetic.

The Last Theorem, Andrew Wiles, and Modern Math

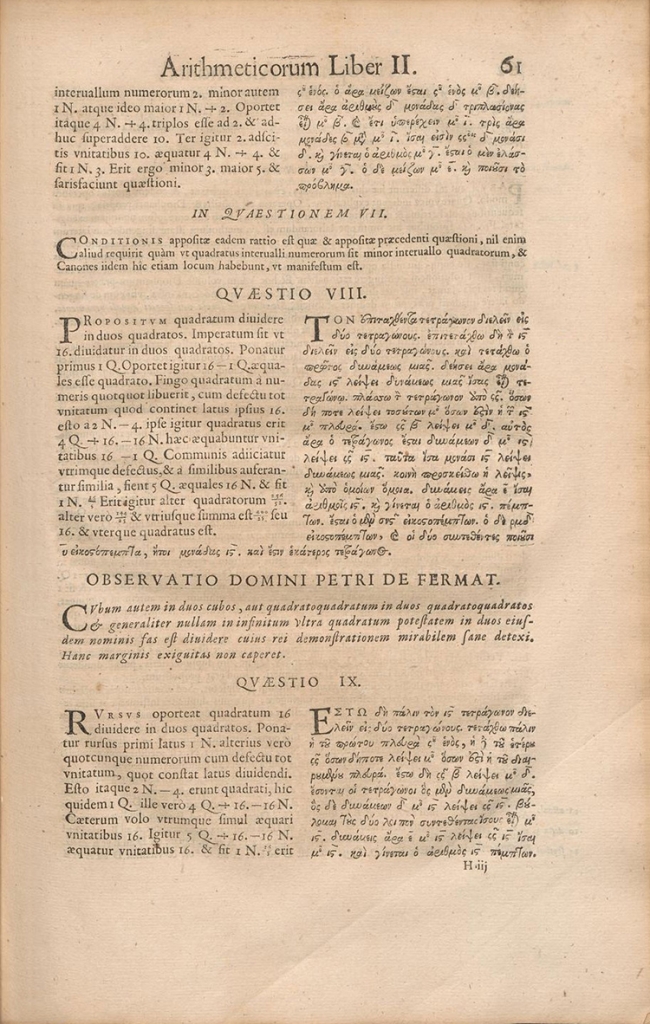

A 1670 edition of a work by the ancient mathematician Diophantus (died about 280 B.C.E.), with additions by Pierre de Fermat (d. 1665). Fermat's note on Diophantus' problem II.VIII went down in history as his “Last Theorem.” (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Fermat's Last Theorem at first glance may remind you of the Pythagorean Theorem—the two are related. Fermat postulated his theorem in the margins of Arithmetica, an ancient Greek mathematics text. His son discovered and published his father's theory later. In his marginalia note, Fermat claimed to have a proof (necessary to technically establish a statement as a theorem). However, none ever materialized from his papers or correspondence.

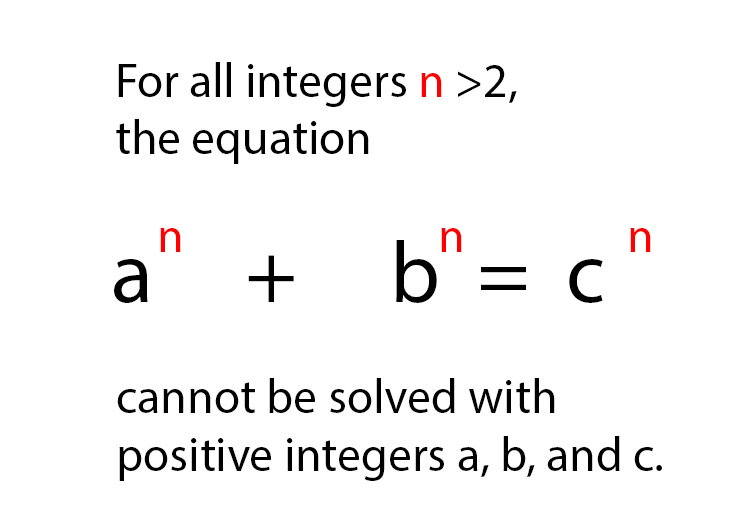

Fermat's Last Theorem is simpler in effect than his Little Theorem. The last Theorem states that choosing from all the positive integers (1 or above), one can never find three distinct numbers (let's call them a, b, and c) which satisfy the below equation. For example, the theorem means that the sum of two cubes will never be the cube of another integer. Pick three random positive numbers and try it on your phone calculator. You will soon see why—although a conjecture—this theorem seemed so tantalizingly true. (You will notice the exponents must be higher numbers than two. Since ancient days, mathematicians have known about and studied Pythagorean triples—series of three integers which satisfy the Pythagorean equation.)

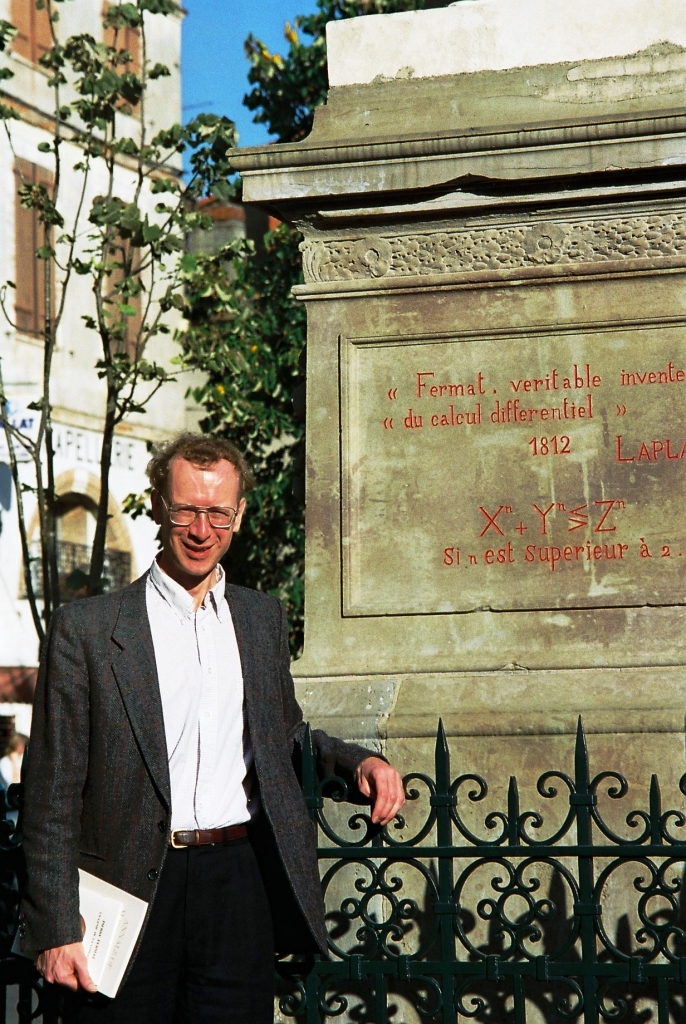

A theorem must be true to apply beyond doubt in every case under its parameters. For 358 years, a proof that the theorem always held true was elusive. Enter British mathematician Andrew Wiles. By the 1980s, progress had been made towards a proof, led by experts in elliptical curves. Wiles specialized in this area and took up the task—one he had dreamed about since childhood. In six years, he worked in intense secrecy on the proof. At a 1993 conference at Cambridge University, Wiles presented a paper entitled “Modular Forms, Elliptic Curves and Galois Representations.” His conclusion of the talk proved an entirely different conjecture.

According to a New York Times article, his “eureka!” moment was actually an understated final comment. By logic and proofs already established, his proof of a different conjecture also proved Fermat's Last Theorem. The Princeton University professor who dreamed of solving a problem set in 1637 had at last done it. Excitement spread through the world of pure math. Countless distinguished scholars had neglected to even touch the conundrum, believing it was unsolvable. In fact, it may have been in Fermat's day. The math used by Wiles was invented much later, and was not available to the early modern genius.

Under intense scrutiny, a flaw in the proof was later discovered. It took Wiles a year to fix. In 1994, he published the fix with former pupil Richard Taylor. If interested in learning more, the saga is well-told in the book Fermat's Enigma by Simon Singh. The mystery was at last solved—the mathematic impossibility that Fermat stated long ago finally cemented as fact. Questions remain. Mathematicians and historians alike have their own opinions on whether Fermat ever truly had the proof he claimed to have. If he did not, he certainly spoke with the confidence of a genius.

Andrew Wiles standing before a statue of Pierre de Fermat in Beaumont-de-Lomagne, France, where Fermat was born. (Photo: Klaus Barner via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Related Articles:

Helpful Infographics Visualize Complex Branches of Math and Science

Who Was Marie Curie? Learn More About This Pioneering Nobel Prize Winner

Scientists Have Discovered a New State of Matter: Liquid Glass

29 Legendary Scientists Came Together in the “Most Intelligent Photo” Ever Taken